Indian regional temples can broadly be categorised into the four cardinal corners of east, west, north and south, together with the recognised central Indian and north-eastern temples. Each of these masterpiece temple architectures possess a unique style of their own, sculpted as they have been by maverick sculptors from mystical times. The regions by which Indian can be designated do possess an archetypal fashion of their own in every sphere of living, depending upon weather and evolution. Quite evidently, a lasting impression is bound to impress upon temple styles, blissfully reflecting these regional singularities from architecture to temple compound and even temple managements.

Indian regional temples can broadly be categorised into the four cardinal corners of east, west, north and south, together with the recognised central Indian and north-eastern temples. Each of these masterpiece temple architectures possess a unique style of their own, sculpted as they have been by maverick sculptors from mystical times. The regions by which Indian can be designated do possess an archetypal fashion of their own in every sphere of living, depending upon weather and evolution. Quite evidently, a lasting impression is bound to impress upon temple styles, blissfully reflecting these regional singularities from architecture to temple compound and even temple managements.

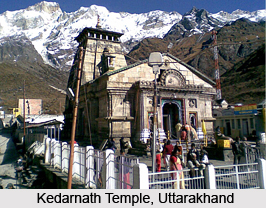

North India, strategically the most crucial part of India, has shaped the course of India`s historical and cultural evolution over the last 3500 years. The three chief religions: Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism, the origin of sacred rivers Ganga, Yamuna and sources of many other important rivers lie in northern India. The mighty Himalayas ranging from Jammu and Kashmir to Arunachal Pradesh, safeguarding the country with its almost limitless periphery is also part of northern India. Delhi and New Delhi, the national capital has too witnessed umpteen battles between several emperors and has been ruled by them time and again. As such, such diverse introductions to establishing a region is sure to impact deeply upon its temple structures. Temples from North India behave as the abode of divine and serene compassion and awareness. Miraculous architecture influenced by cultural amalgamations emote profound devotion amongst devotees. It would not be an overstatement in Indian regional temple style if it is stated that north Indian temples ideally mirror the quintessential Indian laid-back living.

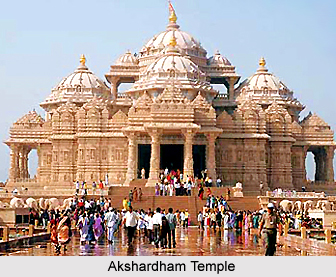

Temples in North India perfectly delineate the archetypal `Nagara` style. The Nagara style had developed in the 5th century and is characterised by a bee-hive shaped tower (called a shikhara, in northern nomenclature) made up of layer upon layer of architectural elements like kapotas and gavaksas. Each of these unusual architectures is all topped by a large round cushion-like element called an amalaka. The arrangement is based on a square, but the walls are sometimes so broken up that the tower often gives the impression of being circular. Moreover, in later developments, like in the Chandela temples, the central shaft was circumvented by many smaller reproductions of itself, creating a spectacular visual effect resembling a fountain. These temples were lucky enough to escape umpteen destructions due to incursions. In this style, the religious structure consists basically of two buildings, the main shrine taller and an adjoining shorter mandapa. The main difference between the two is the shape of the shikhara. In the principal shrine, bell shaped structures add to the additional height. As is usual in all Hindu temples, there exists the kalasa at the top and the ayudha or emblem of the presiding deity. The basic structure of North Indian temples is a room or Garbhagriha (sanctum sanctorum) where the idol of the main deity is preserved. Under Indian regional temples, a north Indian temple is approached by a flight of steps and is often erected upon a platform. A porch covers the entrance to the temples, which is further supported by carved pillars. A striking roof called the shikhara surmounts the top of the garbhagriha and commands the environs. As time passed, small temples germinated into enormous temple complexes. Some north Indian temples also possess a hall or mandap from where one can directly move into the sanctum sanctorum.

Temples in North India perfectly delineate the archetypal `Nagara` style. The Nagara style had developed in the 5th century and is characterised by a bee-hive shaped tower (called a shikhara, in northern nomenclature) made up of layer upon layer of architectural elements like kapotas and gavaksas. Each of these unusual architectures is all topped by a large round cushion-like element called an amalaka. The arrangement is based on a square, but the walls are sometimes so broken up that the tower often gives the impression of being circular. Moreover, in later developments, like in the Chandela temples, the central shaft was circumvented by many smaller reproductions of itself, creating a spectacular visual effect resembling a fountain. These temples were lucky enough to escape umpteen destructions due to incursions. In this style, the religious structure consists basically of two buildings, the main shrine taller and an adjoining shorter mandapa. The main difference between the two is the shape of the shikhara. In the principal shrine, bell shaped structures add to the additional height. As is usual in all Hindu temples, there exists the kalasa at the top and the ayudha or emblem of the presiding deity. The basic structure of North Indian temples is a room or Garbhagriha (sanctum sanctorum) where the idol of the main deity is preserved. Under Indian regional temples, a north Indian temple is approached by a flight of steps and is often erected upon a platform. A porch covers the entrance to the temples, which is further supported by carved pillars. A striking roof called the shikhara surmounts the top of the garbhagriha and commands the environs. As time passed, small temples germinated into enormous temple complexes. Some north Indian temples also possess a hall or mandap from where one can directly move into the sanctum sanctorum.

Flamboyantly erected and aesthetically contrived, the temples of South India are unmatched in architectural brilliance. But more than being just symbols of architectural brilliance, these temples are living embodiments of rich tradition and culture that has made India proud. Southern India is specked and scattered with places of religious pursuit. In fact, there exist several towns that are referred to as the `temple towns` on account of their grandeur and the temples they are home to. Rameshwaram can perfectly be named as an island of Lord Rama`s temple in Tamil Nadu. Along with serving as a major pilgrimage for the Hindus, Rameshwaram doubles itself as a happening holiday destination too.

Indian regional temples and its architecture are broadly divided into northern and southern styles, classified by the form and shape of the shikhara and the individuality of its decoration.

The shikhara of the temples in South India tend to be created up of distinctive horizontal levels that diminish to form a rough pyramid. Each level is further decorated with miniature temple roof-tops. The shikhara of the temples in North and Central India, in contrast, corresponds to an upturned cone that is decorated with tiny conical shikharas. Some temples had even developed their own local flavour, apart from adhering to their basic aboriginal style.

The shikhara of the temples in South India tend to be created up of distinctive horizontal levels that diminish to form a rough pyramid. Each level is further decorated with miniature temple roof-tops. The shikhara of the temples in North and Central India, in contrast, corresponds to an upturned cone that is decorated with tiny conical shikharas. Some temples had even developed their own local flavour, apart from adhering to their basic aboriginal style.

Architecture in south Indian temples was the singular style that had matured in the Dravida Desam. The Vimana and the Gopurams are the distinguishing characteristics of the southern regional temple style in India. Vimana represents a soaring pyramidal tower, consisting of several progressively smaller storeys. The structure stands on a square base. The gopuram, on the other hand, has two storeys separated by a horizontal molding. The Prakara or the outer wall envelops the main shrine as well as the other smaller shrines and the tank. The Pallavas, the Cholas, the Pandyas, the Vijayanagara rulers and the Nayakas had all unanimously contributed to the southern style of temples.

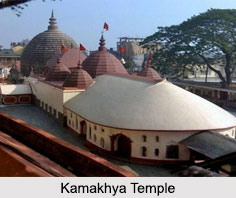

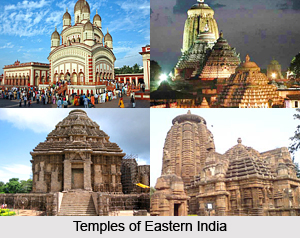

East India is known to proliferate in both natural and man-made riches; the region also mysteriously doubles up as a travelers` paradise. Indian regional temples have since time immemorial been redefined and cultured through the stellar presence of East Indian temples. A visit to the temples from this region lets one to soak soulfully in the unruffled atmosphere from the environs, where life is cultured and serenity pervades everywhere. Bodhi Temple, Lingaraja Temple, Jagannath Temple, Maha Bodhi Temple, Dakshineshwar Kali Temple are some of the few religious institutions that forever etches a place in memory lane. Due to their separate regional development, some portions of an East Indian temple bear a different nomenclature than what is used elsewhere in India. For instance, the part of the temple that contains the shrine is called a deul in Orissa, but a vimana everywhere else. East Indian temples valiantly integrate a northern-style tower, or rekha deul in the Orissan dialect, with a southern-styled hall. The pattern of the tower corresponds to the one from Khajuraho in the Deccan region, while its adjoining hall characteristically bears a pyramidal-shaped roof. That roof atop the hall is additionally sculpted in rows named pidha (also mentioned as "pida"). Above the pidha there can be witnessed a ghanta ("bell," named after its shape), the whole edifice being crested by a kalasha-type ("pot") finial.

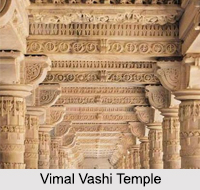

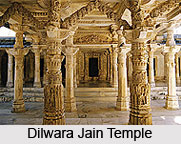

Indian regional temples complete the full square of maverick architecture and magnificence with West Indian temples at the forefront. Empowered with the inner eye for detailed decoration, passion for work and adulation for all things beauteous has helped West Indian sculptors to infuse life into lifeless stones and chisel masterpieces from them. There can be no superior way to prove the above statement than to pay a visit to the temple clusters in west India, where elaborately contrived columns and pillars of temples are ready to attest a trial. Magnificently chiseled temples are one of the prime attractions of this `never-never land` that is nevertheless one of the major industrial regions of the country. Dwarka, Rukmini Temple, Dwarakadhisha Temple, Somnath Temple, Gujarat are some of the religious abodes that are most revered in west India. The temples constructed in western India within a crucial period of post-Christian era, signify one of the richest and most luxuriant evolutions of Indo-Aryan architectural style.

This post-Christian era is re-drawn by Muhammad Ghana`s expedition to Somnath in Kathiawar in 1025-26 A.D. and the epoch within the conquest of this part of the country by Sultans of Delhi in 1298 A.D. The mayhem and devastation caused by Mahmud of Ghazni`s maraud, however, did not last long. The Solanki rulers, reigning family during Ghazni`s plunder, were a stable and powerful dynasty who lost no time or energy in compensating the damages done. Contrary to what one might expect, Mahmud of Ghazni`s campaign of desecration seems to have lent an added drive and momentum to temple building in the non-violent period that followed. The immense prosperity of the Solanki Dynasty was due largely to the geographical positioning of Gujarat which was then the focal-centre of West Indian commercial merchandising. This was another factor which influenced the religious architecture of this region, because there does retain clandestine lavishness within the construction, which speaks of both material and emotional wealth.

This post-Christian era is re-drawn by Muhammad Ghana`s expedition to Somnath in Kathiawar in 1025-26 A.D. and the epoch within the conquest of this part of the country by Sultans of Delhi in 1298 A.D. The mayhem and devastation caused by Mahmud of Ghazni`s maraud, however, did not last long. The Solanki rulers, reigning family during Ghazni`s plunder, were a stable and powerful dynasty who lost no time or energy in compensating the damages done. Contrary to what one might expect, Mahmud of Ghazni`s campaign of desecration seems to have lent an added drive and momentum to temple building in the non-violent period that followed. The immense prosperity of the Solanki Dynasty was due largely to the geographical positioning of Gujarat which was then the focal-centre of West Indian commercial merchandising. This was another factor which influenced the religious architecture of this region, because there does retain clandestine lavishness within the construction, which speaks of both material and emotional wealth.