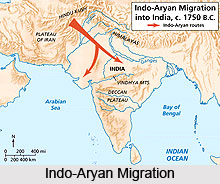

Certain tentative ideas about Indian races were aired in the second half of the nineteenth century, but towards the end of the century a systematic racial classification of Indian people was in place, with the Aryans at the top of the postulated hierarchy. Basically all the major groups that existed in the Indian race system, including the Aryans, were interpreted as having come from outside. The early corpus of Sanskrit literature was also the earliest extant record of the Aryan literature, and from this point of view, it is hardly a matter of surprise that the German Romantics would be enamoured of the beauties of Indian literature and philosophy. The third major ingredient of Indology of this period was a carefully constructed dichotomy between ancient India and the modern India and Indians. By the time the British came as rulers, the ancient Aryan civilization of India was degraded, and its rejuvenation could take place only under the British rule which in fact was a modern Aryan rule, because linguistically and racially the Anglo-Saxons were placed within the pristine Aryan fold.

Certain tentative ideas about Indian races were aired in the second half of the nineteenth century, but towards the end of the century a systematic racial classification of Indian people was in place, with the Aryans at the top of the postulated hierarchy. Basically all the major groups that existed in the Indian race system, including the Aryans, were interpreted as having come from outside. The early corpus of Sanskrit literature was also the earliest extant record of the Aryan literature, and from this point of view, it is hardly a matter of surprise that the German Romantics would be enamoured of the beauties of Indian literature and philosophy. The third major ingredient of Indology of this period was a carefully constructed dichotomy between ancient India and the modern India and Indians. By the time the British came as rulers, the ancient Aryan civilization of India was degraded, and its rejuvenation could take place only under the British rule which in fact was a modern Aryan rule, because linguistically and racially the Anglo-Saxons were placed within the pristine Aryan fold.

In one sense this offered a kind of legitimacy to the British rule and European dominance in general, and the premise could also satisfy the Indian upper castes because through their ancient Aryan affiliation they could claim cousinship with their rulers. The German Romantic concern with the ancient Sanskrit literature and philosophy has had the effect of partly hiding the belief that all major changes in Indian culture and society could come to India only from outside. Presently, it is an acknowledged part of modern historical scholarship that various socio-political issues affect the way in which the past is reconstructed at a given point of time.

As per the People of India project undertaken by the Anthropological Survey of India between 1985 and 1992, the approximate number of the communities has been traced as 4635, located and studied in all states and Union Territories of India, related only to modern India. At the centre lies the concept of `race`. Indian race has been considered a better term than caste, tribe and other non-caste categories because the original aspects of these latter categories have been breaking down in modern India. In view of the breakdown or weakening of their traditional features, commu¬nity, or to use an Indian term, `samudaya`, seems to be a more appropriate concept for an all-India reference than caste with its various local names. The second major point to note in this context is that a community is a dynamic category, continually redefining itself, its relationship with other communities and with its social and physical environments.

In the modern India, the study of races involves four types of communities. The first type com¬prises very large categories, including castes and minorities. The second type denotes mostly the major linguistic and cultural categories, such as the Assamese, Bengali, Oriya, etc. Even when they emigrate they are known by the state and the language area to which they belong. There is a third type of community, only about half a dozen of them which does not conform to the three-fold criteria of endogamy, occupation and percep¬tion. The fourth type of community like Adi Dharma, Adi Karnataka, Adi Andhra, etc., came up in the wake of the constitutional reforms of the 1920s and 1930s and continues to figure in the Government of India list of `scheduled castes`.

In the modern India, the study of races involves four types of communities. The first type com¬prises very large categories, including castes and minorities. The second type denotes mostly the major linguistic and cultural categories, such as the Assamese, Bengali, Oriya, etc. Even when they emigrate they are known by the state and the language area to which they belong. There is a third type of community, only about half a dozen of them which does not conform to the three-fold criteria of endogamy, occupation and percep¬tion. The fourth type of community like Adi Dharma, Adi Karnataka, Adi Andhra, etc., came up in the wake of the constitutional reforms of the 1920s and 1930s and continues to figure in the Government of India list of `scheduled castes`.

Of the 4635 identified races in India, there are 2209 main communities with 586 segments (mostly major). The division of Indian races categorise in the basis of their occupation and culture. Even a brief listing of these communities is not a matter pof concern, but one can certainly point out the infinite background factors leading to their community perceptions and identifications. In many cases, it is the nature of occupation. The places of origin, religious affiliation, food habits, languages, tradition etc can also identify a particular race. The narration is almost endless. Sometimes, there are markers of dress, ornaments, body-markings, etc. also play important part to denote particular races.

In the basis of language, the study of Indian races defines that an overwhelming number of communities are linguistically homogeneous. There are wide variations in the range of social organizations, beginning with clan organizations, mar¬riage patterns, marriage symbols, and so on. Many of these variations are related to status, power and dominance of various community segments. The concept of purity and pollution is very important in allocating places in the basic social hierarchy which is by and large conditioned by the four¬fold vama system, including the fifth category of untouchables. There are dual vama categories in 104 communities. The hierarchical divisions within a community can be impressive; but what is interesting now is that many of these dis¬tinctions are gradually disappearing and there is more emphasis on the identity of the community as a whole with the formation of political asso¬ciations. Religious affiliations also are not static; there are various levels and forms of Hinduism, from monism to plain shamanism. The survey identified 70 traditional rural occupations, with the artisan communities having a countrywide distribution. Some of the widely distributed occupa¬tional groups are leather-workers (Chamars), mendicants and beggars (Jogis), potters (Kumhars), oil-pressers (Kalu) and barbers (Nai).

The image of diversity notwithstanding, society is not perceived to be fragmented by Indians. On a theoretical level this sharing of space, ethos and cultural traits is better explained by the results of a much earlier Anthropological Survey of India study of the distribution of the material traits of life in the country.

The relevant material traits were forms of villages, types of cottages, staple diet, oils and oil-presses, ploughs and husking implements, male and female dresses, footwear and bullock-carts. Some degree of regionalism is evident in the distribution of these traits and further this regionalism seems to be on the whole independent of language as well of physical types.

The relevant material traits were forms of villages, types of cottages, staple diet, oils and oil-presses, ploughs and husking implements, male and female dresses, footwear and bullock-carts. Some degree of regionalism is evident in the distribution of these traits and further this regionalism seems to be on the whole independent of language as well of physical types.

The degree of differentiation in Indian race is said to be less in respect of the country`s social organization. Similarities are many between the various castes and the linked productive organizations in different parts of the country, the distinction being based on finer shades only. Besides, as one considers other spheres of life, namely things like laws which guide in¬heritance or define the rights and duties of individuals in a kin group. They are eventually replaced by a unity of beliefs and aspirations which gives to Indian civilization a character of its own.