Indian language movements specify those troubled and conflicting moments, in which the nation had witnessed surging protestations supporting the sponsorship of a specific language. And these protestations were such that it took on the shape of national and historical movements.

Indian language movements specify those troubled and conflicting moments, in which the nation had witnessed surging protestations supporting the sponsorship of a specific language. And these protestations were such that it took on the shape of national and historical movements.

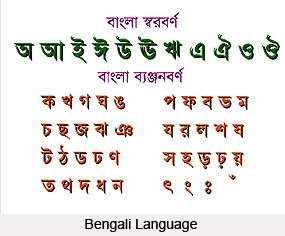

Before looking deep into the language movements in India, it is necessary to comprehend the framework of Indian languages and their umpteen usages in day-to-day lives. With almost an uncountable number of languages being spoken by each society in village or city, the uniqueness lies in the fact that no two communities are alike in terms communication. North India, for instance differs wholly from West India in every sphere.

Likewise, the language groups in India are also classified into two headers, namely Indo-Aryan languages and Dravidian languages. Holding in a variety of language styles and dictions, these languages have time and again been dominated and predominated by some ruler, who was in favour of patronising a different language. As such, the principal language turned capable to overshadow its aboriginal counterpart quite successfully.

Urdu Language Movement in India

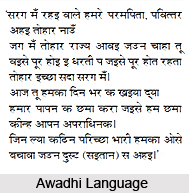

Language movements in India have existed since ancient historical times, involving political and administrational juggling. These near-uprisings were sufficient enough to stir layman population, creating a factional separation between two or more language groups. First trace of any Indian language movement dates back to the culminating Mughal Empire, with the emergence of Urdu Language Movement. Urdu Movement was essentially a socio-political movement, purported at making Urdu the universal language and emblem of cultural and political individuality of the Muslim communities of India. The movement began with the decline of the Mughal Empire in the mid-19th century, fuelled by the Aligarh Movement under Sir Syed Ahmed Khan. It had indeed profoundly influenced the yet-to-arrive All India Muslim League and the Pakistan movement.

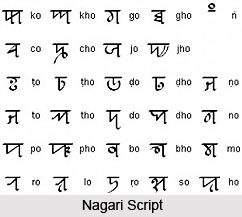

Urdu Movement under the Indian language movements had its root during the early years in British domination, prior to Queen Victoria`s direct annexation. The Hindi-Urdu controversy rose up in 1867, when the British government came to a decision to comply with an unusual demand of Hindu communities. Hindus from United Provinces (present day Uttar Pradesh) and Bihar had planned to change the Perso-Arabic script of the official language into Devanagari and embrace Hindi as the second official language.

One of the most influential Muslim politicians at that time Sir Syed Ahmed Khan had turned fiery to voice out his opposition against this change; he had always regarded Urdu as the lingua franca of Islamic followers. Urdu was an out-and-out evolvement within India and it was used as a subaltern language to Persian, official language of the Mughal court. Since the fall of the Mughal dynasty, Sir Syed Ahmed Khan vehemently had promoted the utilisation of Urdu through his writings. Under his leadership, the Scientific Society of Aligarh interpreted Western works solely into Urdu. The master was of the view that Urdu was "a common legacy of Hindus and Muslims". As such, the large section of Hindus demanding for Hindi, led Sir Syed to believe that it was a corrosion of the centuries-old Muslim cultural ascendancy upon India. Bearing witness in front of the British-appointed education commission, Sir Syed had controversially exclaimed "Urdu was the language of gentry and Hindi that of the vulgar." Consequently, his remarks enkindled an antagonistic response from Hindu leaders and advocates of Hindi. Throughout the nation, Hindus united to insist on the recognition of Hindi. Victory of the Hindi movement led Sir Syed Ahmed Khan to additionally promote Urdu as the emblem of Muslim heritage and as the language of Muslim `intellectual and political class`. He also had sought to convince the British to give Urdu widespread official usage and patronage.

Pure Tamil Movement in India

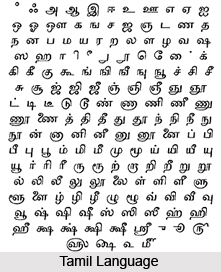

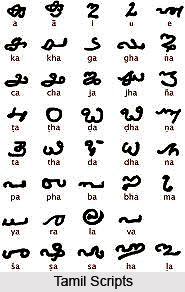

Independent India also had remained witness to significant language movements, amongst which the Pure Tamil Movement became successful to agitate the nation at large. Indeed, the noticeable factor here is that whenever language movements in India have cropped up due to some specific reason, extensive religious, social, political and caste anarchy and division came to light. There had occurred some significant conflicts over linguistic rights in India. The first major linguistic conflict in free India had taken place in Tamil Nadu against the implementation of Hindi as the official language of India, known as Anti-Hindi agitations.

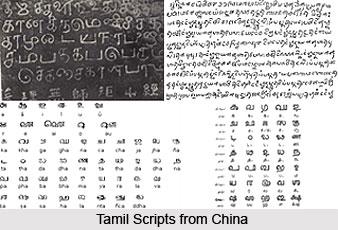

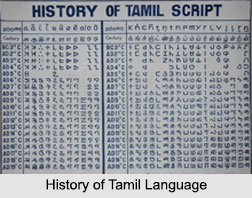

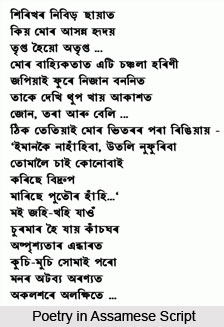

Pure Tamil Movement is also popular as Thanittamil Iyakkam and Only Tamil Movement. It essentially acted as a movement of `linguistic purism` (a language kind as differentiated from other purer varieties, often denoting a seeming fall from an ideal past or an unwanted similarity with other languages) in Tamil literature, which essayed to imitate the "unadulterated Tamil language" of the Sangam period. Tamil language movement had consciously kept off Sanskrit, Persian and English loanwords from their diction and dialect. Tamil insurgence had notably come up time and again through the authorships of G. Devaneya Pavanar, Maraimalai Adigal and Paventhar Bharathidasan, Pavalareru Perunchitthiranaar. The movement gained additional fuel and propagation under the Thenmozhi literary magazine, founded by Pavalareru Perunchithiranar. V.G. Suryanarayana Sastri, prevalently known as "Parithimar Kalaignar", a Brahmin had acted as a 20th century striking figure of the movement. As early as 1902, Suryanarayana Sastri had in fact demanded classical language status for Tamil.

Indian language movements had received considerably impetus through Tamil Movement and its after-effects upon Indian society. Since Indian Independence, Tamil had been preferred by language strategies and policy makers. However, Tamil had been under regular usage in high schools since 1938 and in university education from 1960. In 1956, the then Indian National Congress government passed a law establishing Tamil as the official language of the state. In 1959, the Tamil Development and Research Council was framed. This body is committed in producing the Tamil school and college textbooks in natural and human sciences, accounting, mathematics, etc. Serial publications of children`s encyclopaedias in Tamil, "lucid commentaries" on Cankam (Sangam literature of Tamil Nadu) poetry and an "authentic history of the Tamil people" appeared in succession, in 1962-63.

Adding further fuel to fire in this Indian language movement, the Congress government had also rejected a number of demands, including the use of "Pure Tamil" instead of "Sanskritised Tamil" in schoolbooks and withholding the name change from Madras to Tamil Nadu until 1969. The Central administration was not much concerned to foster separatist movements. This generated additional bitterness among the Tamil puritans. In the elections of the same year, Congress suffered a crushing and much-publicised defeat and was replaced by the DMK government under C. N. Annadurai.