Impact of hunting in India is vast and is considered as a serious threat to a symbolically significant species. With the increasing impact of hunting it was in Ranthambore Tiger Reserve in Rajasthan, one of the finest tiger reserves in the country, where the wildlife crisis first made headlines. By mid-1992, after several official denials of tiger poaching, it became clear that over a dozen of great cats had been killed. In the past, hunters had mainly killed the animals to supply markets in the Western world with tiger-skins. But the new round of unlawful snaring and poisoning was aimed at servicing growing overseas and home markets for age-old therapeutic systems that use tiger-parts. A cluster of changes in the political and economic ambience made the older model of wildlife conservation more unfeasible in the face of the new pressures.

Impact of hunting in India is vast and is considered as a serious threat to a symbolically significant species. With the increasing impact of hunting it was in Ranthambore Tiger Reserve in Rajasthan, one of the finest tiger reserves in the country, where the wildlife crisis first made headlines. By mid-1992, after several official denials of tiger poaching, it became clear that over a dozen of great cats had been killed. In the past, hunters had mainly killed the animals to supply markets in the Western world with tiger-skins. But the new round of unlawful snaring and poisoning was aimed at servicing growing overseas and home markets for age-old therapeutic systems that use tiger-parts. A cluster of changes in the political and economic ambience made the older model of wildlife conservation more unfeasible in the face of the new pressures.

With time purchasing power of consumers in Asia and North America also increased tremendously. It had given the age-old medical remedies a new lease of life, even as they meant death for the entire generation of tigers in the forests. The rates of extraction increased to meet the surge in demand. Some experts went so far as to argue that direct elimination through such attacks had more destructive potential for the tiger population than did indirect attrition through habitat loss. Field biologists still stressed the need to protect intact expanses of habitat, prey and all, rather than isolate the trade alone as a depletive factor.

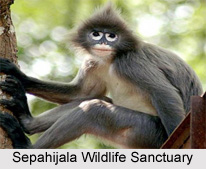

The machinery of enforcement was designed to deal with local-level issues rather than the new highly sophisticated commercial networks. The impact of hunting was not only limited to the tiger reserves, it also included other endangered species. Like for instance, the tiger was not alone in being the object of poaching networks; the great Indian one-horned rhino was also facing troubles. In many smaller preserves in Assam populations of the huge creatures were being rapidly depleted. Similarly, a rise in the price of ivory exerted new pressures on the Asian elephant, with tuskers being selectively killed off in key reserves in southern India.

The machinery of enforcement was designed to deal with local-level issues rather than the new highly sophisticated commercial networks. The impact of hunting was not only limited to the tiger reserves, it also included other endangered species. Like for instance, the tiger was not alone in being the object of poaching networks; the great Indian one-horned rhino was also facing troubles. In many smaller preserves in Assam populations of the huge creatures were being rapidly depleted. Similarly, a rise in the price of ivory exerted new pressures on the Asian elephant, with tuskers being selectively killed off in key reserves in southern India.

This point regarding the impact of hunting remained virtually the sole referral point for officials until it became clear that something was seriously wrong. Several voluntary groups assisted the state governments taking strong measures for the conservation of wildlife species of the country. By the end of the 1990s, various voluntary organisations were funnelling nearly two million dollars a year to the field to supplement official efforts. The largest chunk of funds came from just one group, the World Wide Fund for Nature or WWF. Funds were put to a range of uses like from helping compensate cattle losses to providing equipment for anti-poaching patrols. Some focused on creating a sense of awareness among middle-class constituents and assisting foresters in protection. Others went a step further, helping generate alternate means of livelihood for those living along the perimeter of parks. Public interest litigation also evolved into a major means to push the official machinery to act. Further, some tried to reach out and anticipate local concerns as well. In response to such efforts, the Steering Committee of Project Tiger took a policy decision against the practice of forced relocation of villages from its reserves.

It is said that if given a sufficient living space, and a modicum of protection, even the threat from illegal trade could be minimised, although not entirely eliminated. But, the protective system itself was under strain because of the serious hunting impact as well as the vast changes in India`s political and economic climate. Moreover, the wider crisis in the wildlife of the country manifested itself in several ways.