The history of Vijayanagara in the early fourteenth century, the invading forces of the Delhi Sultanate had swept away the existing kingdoms of the Deccan and southern India and by AD 1328 the whole of the region and been brought under the control of Delhi. Successful revolts, however, soon broke out, resulting in the establishment of independent states in the Deccan, including the Vijayanagara kingdom and the Bahmani Sultanate. There is a disagreement among people about the foundational year of Vijayanagara kingdom. Some suggest that it was founded in 1336 AD but as per some scholars the year AD 1346 has also been suggested. It is likely that the emergence of Vijayanagara`s statehood was a gradual process, till it was firmly established by the mid-fourteenth century.

The Vijayanagara kingdom, up to AD 1565, was ruled by three dynasties namely the Saiigama (AD 1336-1485), the Saluva (AD 1485-1505) and the Tuluva dynasty (AD 1505-70). The first king, Harihara I, (AD 1336-56), the eldest of the five sons of Sangama, built up within a few years a kingdom stretching from coast to coast. During the latter part of his reign, the Bahmani kingdom emerged beyond the Krishna River and its establishment commenced an era of constant warfare between these two kingdoms. Harihara I was succeeded by his brother Bukka I (AD 1356-77), whose great achievement was the conquest of the Tamil country.

Harihara II (AD 1377-1404) was the first ruler of the dynasty to assume the imperial title of Maharajadhiraja. His reign witnessed the expansion of the Vijayanagara kingdom over the whole of southern India, south of the river Krishna. On the death of Harihara II, there was a dispute over the succession among his three sons, Virupaksa II, Bukka II and Devaraya I, but ultimately it was Devaraya I who secured the throne and then ruled from AD 1406 to 1422. His rule was followed by the short reigns of his sons, Ramacandra and Vira Vijaya. The latter was succeeded by his son Devaraya II (AD 1424-1446), the greatest of the Sangama line. After meeting with reverses in wars against the Bahmanis, Devaraya II introduced reforms in his military and employed Muslims, especially in the archery and cavalry contingents. The glorious reign of Devaraya II was followed by a period of decline and disorder during the period of Mallikarjuna (AD 1446-65) and Virupaksa II (AD 1465-1485). The dismal rule of these last Sangamas facilitated the rise to power of Saluva Narasimha, who usurped the throne.

Sajuva Narasimha (AD 1485-1491) was an able ruler who set himself to restore the strength and prestige of the kingdom. He was succeeded in turn by his minor sons, Timma (AD 1491) and Immadi Narasimha (AD 1491-1505), who were guided by their regent, the Tuluva minister Narasa Nayaka and later his son Vira Narasimha, who consequently eliminated the Saluva sovereign and assumed full power. With this second usurpation the Tuluvas attained the throne and established their control on the kingdom. Vira Narasimha (AD 1505-09) was, after a short reign, succeeded by his half-brother Krisnadevaraya.

Krisnadevaraya (AD 1509-1529) was not only the greatest king in Vijayanagara history, but was also one of the most brilliant monarchs in medieval India. He renovated dilapidated temples throughout his kingdom, built new ones and gave munificent gifts and grants to temples and religious men. Achyutaraya (AD 1529-1542), who succeeded his half-brother Krisnadevaraya on the throne, was also a capable military ruler and a liberal patron of arts and letters. In the power struggle that broke out on Achyutaraya`s death, the faction led by Krisnadevaraya`s son-in-law, Ramaraya, triumphed and Sadasiva, a nephew of the previous ruler, was placed on the throne. Ramaraya entangled himself in the interstate rivalries of the Deccan Sultanates that had been formed after the disintegration of the Bahamani kingdom. As a result of alliances and wars, Vijayanagara regained territory lost after Krisnadevaraya`s reign and even extended its limits. But, in the long run, Ramaraya`s policy proved disastrous. The Deccan Sultanates, alarmed at the growing power of Vijayanagara, temporarily buried their differences and in a joint action, defeated Ramaraya and the Vijayanagara forces in the decisive battle of Tajikota in January AD 1565. Following this climacteric, the capital city, Vijayanagara, was temporarily occupied and sacked by the allied armies of the Deccan Sultans. The Vijayanagara state never recovered completely from the catastrophe of Tajikota which resulted in the abandonment of the capital and the loss of the northern parts of the kingdom. The truncated kingdom lingered on in the south under the Aravidu dynasty (AD 1570-1646), while its feudatories broke away one after another and acquired independence.

Krisnadevaraya (AD 1509-1529) was not only the greatest king in Vijayanagara history, but was also one of the most brilliant monarchs in medieval India. He renovated dilapidated temples throughout his kingdom, built new ones and gave munificent gifts and grants to temples and religious men. Achyutaraya (AD 1529-1542), who succeeded his half-brother Krisnadevaraya on the throne, was also a capable military ruler and a liberal patron of arts and letters. In the power struggle that broke out on Achyutaraya`s death, the faction led by Krisnadevaraya`s son-in-law, Ramaraya, triumphed and Sadasiva, a nephew of the previous ruler, was placed on the throne. Ramaraya entangled himself in the interstate rivalries of the Deccan Sultanates that had been formed after the disintegration of the Bahamani kingdom. As a result of alliances and wars, Vijayanagara regained territory lost after Krisnadevaraya`s reign and even extended its limits. But, in the long run, Ramaraya`s policy proved disastrous. The Deccan Sultanates, alarmed at the growing power of Vijayanagara, temporarily buried their differences and in a joint action, defeated Ramaraya and the Vijayanagara forces in the decisive battle of Tajikota in January AD 1565. Following this climacteric, the capital city, Vijayanagara, was temporarily occupied and sacked by the allied armies of the Deccan Sultans. The Vijayanagara state never recovered completely from the catastrophe of Tajikota which resulted in the abandonment of the capital and the loss of the northern parts of the kingdom. The truncated kingdom lingered on in the south under the Aravidu dynasty (AD 1570-1646), while its feudatories broke away one after another and acquired independence.

Although the kingdom eventually disintegrated, the monarchs left a rich legacy. The Vijayanagara state created conditions for the promotion of Hindu culture and institutions. The encouragement of religion by the Vijayanagara monarchs, as revealed by the numerous inscriptions, included the promotion of Vedic and other studies, the support of Brahmans, the generous patronage extended to temples and monasteries, pilgrimages to religious places and the celebration of public rituals.

Under the patronage of the early Vijayanagara sovereigns, notably Bukka I, a syndicate of scholars undertook the prodigious task of commenting upon the Samhitas of all the four Vedas and many of the Brahmans and Aranyakas. A codification of the philosophical systems was also effected in the `Sarvadarsana-sangraha`. Land in villages and sometimes even whole villages, was granted to individual scholars or to groups of Brahmans. The Vijayanagara rulers themselves undertook tours of pilgrimage and encouraged pilgrimages within the kingdom. They aimed to integrate the different language zones of the realm.

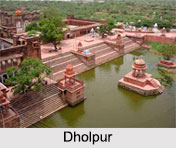

Inscriptions are scattered throughout southern India which record the benefactions to temples by the Vijayanagara rulers. The monarchs and their subordinates built hundreds of new temples, repaired or made extensive additions to several old ones, settled disputes among temple senators and endowed the temples richly with land, money, taxes due to the state and jewels for daily worship or for new festivals that were instituted. Such favour was extended to Shaivite, Vaishnavite and Jain institutions. Besides the state support, temples also enjoyed wide public patronage from private donors such as rich individuals, sectarian leaders, professional guilds and communal groups.

The celebration of public rituals was an important royal duty. It was believed that flourishing festivals would strengthen dharma, ensure that divine powers would protect the kingdom and encourage the heavenly flow of gifts to the king and his kingdom and bestow fertility on the land. During this period the most important of these rituals was, undoubtedly, the annual nine-day Mahanavami festival. This festival, although intrinsically religious in character, had political, economic, social and military significance as well. His kind of celebrations highlights the fact that, in the Vijayanagara system, the relationship between the kings and the gods was one of partnership. Although the king himself was not seen as divine, kingship frequently was, and the great royal rituals were attempts to bring this divine analogy into being.

The transactions between kings, temple deities and priests or sectarian leaders point to a relationship of mutual interdependence. The priests made offerings to and performed services for the gods, the deities preserved the king, his kingdom and his subjects and the monarch protected and awarded material rewards to temples and religious leaders. Prosperity, fertility, success in military ventures, the right relationships between castes and other social groups all resulted, ultimately, from royal activity. Here was a healthy balance among the socio cultural religious and humanitarian relationship among the people of Vijayanagara.