Introduction

Music of Tamil Nadu had their beginnings in the temples. Most of the art forms of Tamil Nadu would represent the culture and rich heritage of people and also their rituals. Originated from the most exquisite forms of artistic skill, the melodious music varieties speak of the rich cultural past of the place.

Music of Tamil Nadu had their beginnings in the temples. Most of the art forms of Tamil Nadu would represent the culture and rich heritage of people and also their rituals. Originated from the most exquisite forms of artistic skill, the melodious music varieties speak of the rich cultural past of the place.

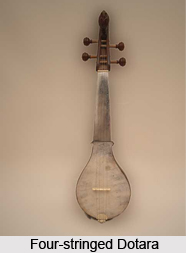

Tamil Nadu is synonymous with the Indian musical maestro of the 18th century, Tyagaraja. The land of Carnatic music, Tamil Nadu is the birthplace of many other music legends as well. Devotional songs in praise of religious deities are commonplace in Tamil Nadu. The main instruments used here are the Violin, Wooden Flute, Veena, Gottuvadayam, Mridangam, Nadaswaram and Ghatam.

History of Music of Tamil Nadu

Music is a very important aspect of the culture of Tamil Nadu, which has a long history and tradition dating back to thousands of years. Different dynasties ruled Tamil Nadu during various phases in history and their overwhelming patronage to art and culture gave the state a great diverse and rich cultural heritage. The classical Tamil literature of the early era called Sangam literature was set to music. Tamil Shaiva saints like Appar, Manikkavasagar used music in their compositions.

Music is a very important aspect of the culture of Tamil Nadu, which has a long history and tradition dating back to thousands of years. Different dynasties ruled Tamil Nadu during various phases in history and their overwhelming patronage to art and culture gave the state a great diverse and rich cultural heritage. The classical Tamil literature of the early era called Sangam literature was set to music. Tamil Shaiva saints like Appar, Manikkavasagar used music in their compositions.

History of music in Tamil Nadu is relevant from the prehistoric times. History has become a shifting, problematic discourse, about any aspect of the world. Art is a complex subject of historical enquiry and aesthetic cognition at each stage of its development. Music is the most abstract of all arts as mathematics is in the region of science. Pure essence of expressiveness in existence is offered in music. In sound, it finds the least resistance and has a freedom unencumbered by the burden of thoughts and facts. It gives it a power to arouse an intense feeling of reality; it seems to be leading into the soul of all things and makes a person feel the very breath of inspiration flowing from the supreme creative joy. In music, the feeling extracted from `sound` becomes an independent object itself. It assumes a tune-form which is definite, but a meaning which is indefinable and yet grips the mind with a sense of absolute truth. After all, art is the response of man`s creative soul to the call of the real.

History of music in Tamil Nadu is relevant from the prehistoric times. History has become a shifting, problematic discourse, about any aspect of the world. Art is a complex subject of historical enquiry and aesthetic cognition at each stage of its development. Music is the most abstract of all arts as mathematics is in the region of science. Pure essence of expressiveness in existence is offered in music. In sound, it finds the least resistance and has a freedom unencumbered by the burden of thoughts and facts. It gives it a power to arouse an intense feeling of reality; it seems to be leading into the soul of all things and makes a person feel the very breath of inspiration flowing from the supreme creative joy. In music, the feeling extracted from `sound` becomes an independent object itself. It assumes a tune-form which is definite, but a meaning which is indefinable and yet grips the mind with a sense of absolute truth. After all, art is the response of man`s creative soul to the call of the real.

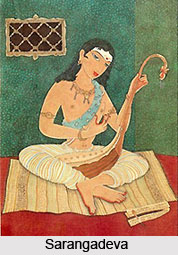

The history of music requires a pre-existent canon pinned down by tradition that is a structured account of the past. An aesthetic canon is a premise of music historiography. The world of Tamil music is fortunate in having inherited a rich legacy of Lakshanagranthas. The authors of these Granthas have made a scientific and systematic study of art-forms. The classical arts derive vitality and strength from these treatises, which provide the structural framework relating to the rendering of these arts. But `True Music` attempts to make people believe in the contextual representation of the world. In the Indian state of Tamil Nadu the first stage of the attempt is marked by sacrifice, characterized by ritual practices. Right from this stage, music is a professional activity. During the Bhakti phase the Azhwars and Nayanmars made use of it as a medium to propagate religious dogma. The Nayaka and Maratha rule reveals the potential of music as a saleable asset.

An endless period of `reproduction` follows, matching the creation of demand. Music compositions are canonized and catalogued. The trend continues till this day. In this process of transformation arises a symbolic confrontation between joyous enjoyment and austere power. The signification of music becomes a relation embedded in specific culture. A musical message is expressed in a global fashion in its operationality; it is no longer a mere juxtaposition (signification) of each sound element. In the course of their fluctuating history, the Tamils have not suffered a total overthrow. Most of the threads are intact. The sequence of development components runs parallel to the renovation of culture. Music gains a meaning operationally beyond its own syntax, since music falls within the very power that produces society.

During the age of the Pallavas, music grew in a fertile soil and climate well irrigated by the Bhakti. The Azhwars and Nayanmars form a conglomeration whose element and social status vary considerably. They belong to different castes. In Sangam and Silappathikaram days Panar were the custodians of music and classified as low born. Music and dance have become a part of temple service under the Pallavas. Association with temples imparts a divinity to the arts and sanctity to the exponents. Temples from now on promote arts.

Musical treatises of the period between the ninth and fifteenth centuries have not survived. In the fifteenth century a giant among composers, Arungirinatha, appeared. Arunachalakavi composed Ramanatakam. The Nayaka and Maratha rulers were great patrons of music and dance. The Nayaka (AD 1532 to 1673) and Maratha (AD 1676 to 1865) provided major institutional support as well. The court at Tanjore had a direct hand in the development of musical theory. The period witnessed the consolidation of musical wealth. Between Tulajendra and Arunachalakavi the crimson dawn was radiant with the promise of glorious sun-shine. Convention clubs Thyagaraja, Muthuswami Dikshitar and Syama Sastri as a Musical Trinity. Many others fill the interval between 1760 AD and 1857 AD.

The institution of reciting (singing) the sacred hymns composed by the first three `Samayacharyas` came into existence in the ninth century AD and that of consecrating their images in the tenth century AD. As endeavours of religious fervour they grew in intensity during the successive four centuries reaching the peak in the thirteenth century AD. The end of the Chola and Pandya rulers records a sudden drop in the degree of intensity of these activities in the fourteenth century AD. The rulers of Vijayanagara Empire of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries attempted to revive the services in some of the temples. Their efforts in this direction did not help to recreate the status. Vijayanagara leaders were preoccupied with architectural expansion and sculptural embellishment.

The period of the Nayaka kings of Tanjore was one of splendour and richness of output, the immediate corollary of the period of Krishnadeva Raya of Vijayanagara. Nayaka patronage could be epitomized. It manifested itself in the shape of (a) the appointment of professional composers, performers to serve in the court, (b) the construction of an auditorium, (c) the concerts in the royal durbar, (d) liberal grants of lords to musicians and artists, (e) extension of facilities for cultural exchange, (f) encouragement to manufacture of musical instruments, (g) appointment of supervisors to direct the execution of schemes, and (h) endowments to temples for purposes of maintaining artists.

The seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries witnessed unprecedented progress in the theory and practice of Tamil music. The roots of the arts of dance and music, which are current, could be traced back to this epoch. By the time of the rule of the Tanjore Nayakas, the Laksbanagrantbas (musical treatises) had been accepted. They lent support for the consolidation of `Art Music`. The veena with twenty four frets had ushered in the Tanjore melam. Venkatamakin systematized the seventy-two melakartas and laid the foundation of the edifice. Lakshana and Lakshya (theory and practice) were happily blended and the best music talents flocked to Tanjore. Musical formats like Kriti, Kirtana, Varna, Ragamalika etc., are not cited as lakshyas. They must have gained currency not classification. Ragas had come to be a group under the seventy-two melakarta scheme.

Past views are not suppressed by successors. The initiative for innovation patently operated during Nayaka-Maratta rule of the Tanjore. The `element of function` had not been irrelevant. The functional notion clearly dominates the court-music of Tanjore, but at the same time the representational aesthetic drawing from ancient theories had not been a casualty. A healthy relation grew between the ends that music was intended to serve and the technical means considered being appropriate to achieve that end. There had been no confrontation between ends and means.

Musical works might have outlived the musical culture of their age but history and aesthetic exist in a reciprocal relation in music history. The aesthetic premises that might sustain the writing of music history are themselves historical. With some leeway in chronology and some stretching of fact, it can safely be said that the art theory of Tamil music was based in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries on the relationship of compositional techniques but relate to social foundations of the Sangam age.

Categories of Music of Tamil Nadu

Music of Tamil Nadu can be categorised under classical, devotional and folk music.

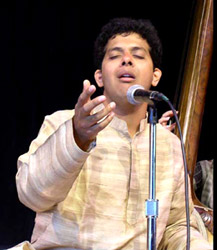

Classical Music: Carnatic music is the classical music form of South India which has a long history in Tamil Nadu. This music has been handed down through generations of artistes. This divine art form is said to have originated from the Gods in ancient times and references have been made in various scriptures, epics and puranas. The three great composer saints popularly referred to as the "Trinity of Carnatic Music"; Tyagaraja, Muthuswami Dikshitar and Syama Sastri were from Tamil Nadu.

Devotional Music: In ancient times, leaders or officers in the world of music called "Thevara Nayakams" arranged the private worship of Kings and group singing. The devotional Thevaram songs were offered in the temples by Sthanikars, Odhuvars or Kattalaiyars. The saints, seers and composers composed the songs as an offering to God. The devotional songs established a direct connection between the spiritual and physical realms of the devotee.

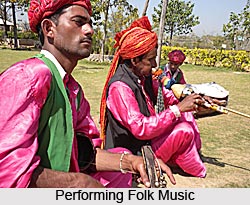

Folk Music: Tamil folk music is famous for its tala intricacies and very ancient ragas. Some of them are Villu Pattu, Music of the Hill Tribes, Music of the Kulava and Nayyandi Melam.

Role of Music in Tamil Nadu

Role of music in Tamil Nadu has helped in the development of musical culture in the state. History Indian art is the product of tradition. The most important characteristic of the Indian music tradition is its melodic form as distinguished from music based on harmony. Rhythm and melody have had a parallel development. In its heteronomy art-experience is ramified into several aspects and divisions. Rhythm and melody are primarily aids to dance and drama. Drama, dance and all other branches of fine-arts were in need of compositions set to music to effectively communicate to the audience the chosen themes. The heterogeneous character of the music and rhythm has been but natural.

Role of music in Tamil Nadu has helped in the development of musical culture in the state. History Indian art is the product of tradition. The most important characteristic of the Indian music tradition is its melodic form as distinguished from music based on harmony. Rhythm and melody have had a parallel development. In its heteronomy art-experience is ramified into several aspects and divisions. Rhythm and melody are primarily aids to dance and drama. Drama, dance and all other branches of fine-arts were in need of compositions set to music to effectively communicate to the audience the chosen themes. The heterogeneous character of the music and rhythm has been but natural.

Natyashastra written by Bharata is the acknowledged earliest extant literature on the subject of `dance`. The term `natya`, includes all the artistic elements of theatre art. Dance had been a part of drama; probably Drama could also have been a part of dance. It is difficult to discern a bifurcation between these branches of art. As made out `natya` in its complete form includes music, dance and communication through expression. References available in early Tamil literature (Cilappathikaram particularly) suggest that dance and drama were one and the same to begin with and in course of time Indian drama slowly emerged as a separate branch. Music had been an inevitable adjunct of both dance and drama.

The art of drama draws heavily on melody and rhythm to effectively communicate Bhava (rasa). Meippaatu in Tamil language is approximately the equivalent of bhava. The renowned Tamil grammar Tolkappiyam has a section entitled Meippattiyal Out of Meippaatu eight rasas (Suvaikat) take their origin. This provision enables any author to narrate the happening to the audience exactly as they are visualised by him. The success scored in this way is to the techniques of composition. The Laya (rhythm) is chosen in consonance with the words used to suit the context. The music adopted is perceptibly a development in steps since the Tamil theatre developed in stages as Marappavaikkuttu, Pommalattam, Torppavaikkuttu, Nilalpavaikkuttu Nattiyam, Nattiyanatakam and Natakam. The renowned Tamil stage actor Awai T.K. Shanmugam claims that the Tamil theatre is a refined form of various dances with individual characteristics mixed. Pallu, Kuravanchi, Nondinatakam and Kuluvanatakam are the adumbrated literary plays. Dramatic adumbrations are a variety of Terukkuttus (enacted in streets) with a style of their own aimed at catering the tastes and on the spot demands of the audience. Themes are mostly love and divinity.

Terukkuttu is staged outside the temple and is an `art of the masses`. Each important character is introduced, the character before introduction being shielded by a hand-held screen. The Guna (calibre) of the character is emphasized through the use of gaits. Principal characters whirl round the stage several times in a fast tempo (Girikai). The professional reckoning of girikai is Ati-talam erardu (eight). Erardu literally means `increasing/ascending`. The folk-artists are not familiar with the angas of a tala. Hence we are not sure whether Ati-tala in the context could be taken as the one currently in use. To assert that Terukkuttu is an early form, we are not armed with tangible evidences (literary or epigraphic). Evidence suggests that in the eighteenth/nineteenth centuries it had been used as a petty means of livelihood by a stock of wandering actors. What they enacted remain as folklores. Many of them were forgotten because of neglect and lack of adequate patronage. In many respects Terukkuttu stands in comparison with the Veethi Natakam of Andhra Pradesh, Payal attam of south-Canara, the Lalit of Maharashtra and the Pavai of Gujarat.

Dance drama is an evolved form and the adumbrations in their format and conduct are almost like full-fledged dramas. They are full of songs. The adumbrations mark a change in the evolution of dramatic-art. A conspicuous fact that the study of early forms of dramatic art projects is that the tunes employed may not conform to the rules of Lakshanagranthas (of later times), it looks as if the very charm and appeal are the result of apparent disregard to the requirements of Lakshana. In the matter of rhythm, the Ati-tala (four or eight unit interval) is apparently universal; the Tisra-eka comes next.

The earliest inscriptions pertaining to dance-art in Tamil Nadu are those found at Arichchalur (1962). The inscriptions are dated AD 200-250. The antiquity of dance tradition is confirmed by these inscriptions. Later evidences suggest that the progress of the art had been unbroken. The Pallavas of Kanchi were great patrons of the dance-art. During the rule of the Vijayalaya Cholas (Tanjai Cholas) one get references to Nanavita Natakasalais (theatres used for varieties of Dramas). Up to this period the Sahityas (texts) in compositions dominate, tune-setting takes a secondary place. Sahityas seem to have been devised to fit into preconceived Varnamettus (tune settings). These are metrical Sahityas. Yet the incontestable fact remains `No music, no poetry`. Different qualitative and quantitative measures of sound are experimented to excite aesthetic pleasure. In an attempt to produce an artistic form, the continua of measured sounds are to be methodically split for alignment. Rhythm becomes the nerve centre. On this basic need the entire range of tones are built. Tone along with rhythm makes the variety (sets of patterns). Rhythm helps to break the monotony. Innovation of patterns had commenced.

When the Tamil theatre attained full stature (as understood currently) cannot be easily ascertained and authentically expressed. Inscriptions at the Brihadeesvara temple at Thanjavur (A.D 984) speak of Rajarajisvara natakam conducted annually in the month of Vaikasi (Tamil). Tiruppantalainallur Pasupatisvarar temple inscriptions refer to Rajaraja Natakam. In one of the inscriptions of Rajaraja Chola I, Tirumala nayanar natakam is mentioned. Tiruppatirippuliyur temple inscriptions mention about Kannavan purana natakam. The form and content of the various plays mentioned are not known since they live only in names. At best, we are able to discern that they are different from Kuttu or adumberation. They are separately referred to and could be identified individually. Some scholars, however, affirm that they are the predecessors of modern Indian theatre.

During the reign of the Nayakas of Thanjavur and their successors, the Marathas, witness unprecedented progress. The Vijayanagara rule in general witnessed an integration of the cultures of Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Kannadiga. Dance and dramas forms undergo a process of elaboration and are presented under new captions. This integrated culture was fostered not only in the imperial capital, but also in the capitals of the provincial Nayakas of Madurai, Gingi etc. Thanjavur city became the cultural centre of the south under the Nayaks of Thanjavur. New and perfected art-forms were evolved in this crucible of culture. The Maratha successors elaborated the idioms and in the true sense set the modern norm for musical and other allied arts.

Dance-dramas Qsai Natya Natakani became popular during this interval. Some of the well known plays are Tyagaraja Vinoda Chitra Prabhandam, Pancharatna Prabhandam, Regunatha Abyudayam, Mannarudasa Vilasam, Chitrakutamahatmyam - many of which works have been published by the Mannar Serfoji Saraswathi Mahal Library.

The opera enacted by men of the Brahmin community (Bagavatars) has its origin at Melattur, near Thanjavur. Popularly known as Bagavatha Mela, it derives inspiration from Narayana Teertha`s Krishna leela tarangini and the Yakshagana play Pariyata apaharanam. Venkatarama Bagavatar of Melattur, an elder contemporary of St. Tyagaraja (Tiruvaiyaru) composed in Telugu, twelve-opera plays based on Puranic themes. These were enacted in the presence of the local deity of the temple. Balubagavatar of Sulamangalam, an adjoining village is another well known exponent of Bhagavata Mela. The actors and the playback musicians moved about all the time (at present the musicians tend to be stationary) before the gaze of the audience. Melattur Virabhadraiah is an important name associated with this art. For the purpose he composed Svarajatis, Varnams, Raga malikas and Tillanas. Perhaps, he is the first to compose Tillanas as indicated by his surname `Margadarsi Virabhadrayya`. Most of his compositions are in Telugu language and Sanskrit language and few are in Tamil language and Marathi languages. These are Mela nataka compositions.

The opera enacted by men of the Brahmin community (Bagavatars) has its origin at Melattur, near Thanjavur. Popularly known as Bagavatha Mela, it derives inspiration from Narayana Teertha`s Krishna leela tarangini and the Yakshagana play Pariyata apaharanam. Venkatarama Bagavatar of Melattur, an elder contemporary of St. Tyagaraja (Tiruvaiyaru) composed in Telugu, twelve-opera plays based on Puranic themes. These were enacted in the presence of the local deity of the temple. Balubagavatar of Sulamangalam, an adjoining village is another well known exponent of Bhagavata Mela. The actors and the playback musicians moved about all the time (at present the musicians tend to be stationary) before the gaze of the audience. Melattur Virabhadraiah is an important name associated with this art. For the purpose he composed Svarajatis, Varnams, Raga malikas and Tillanas. Perhaps, he is the first to compose Tillanas as indicated by his surname `Margadarsi Virabhadrayya`. Most of his compositions are in Telugu language and Sanskrit language and few are in Tamil language and Marathi languages. These are Mela nataka compositions.

Ritualistic Music in Tamil Nadu

Ritualistic music and dances of the temples occupy an important place in the history of music. Festivals connected with the temples had special music and dance items of worship. Temples also promoted the learning of music and dance. The Nayakas were great devotees of Lord Ranganatha of Srirangam, and Rajagopalaswami of Mannargudi. Of the instruments that were used in temple service (Mukhavina, Dande, Kombu, Chandravalaya, Bheri), the use of Nadasvaram is of special interest. For the first time in the history of musical instruments, Nadasvaram finds mention in the Telugu work Kridarambam. It was during the Nayaka period when it was known as Nagasvaram that it also enjoyed great popularity. It has become an indispensable temple instrument of south India.

Ritualistic music and dances of the temples occupy an important place in the history of music. Festivals connected with the temples had special music and dance items of worship. Temples also promoted the learning of music and dance. The Nayakas were great devotees of Lord Ranganatha of Srirangam, and Rajagopalaswami of Mannargudi. Of the instruments that were used in temple service (Mukhavina, Dande, Kombu, Chandravalaya, Bheri), the use of Nadasvaram is of special interest. For the first time in the history of musical instruments, Nadasvaram finds mention in the Telugu work Kridarambam. It was during the Nayaka period when it was known as Nagasvaram that it also enjoyed great popularity. It has become an indispensable temple instrument of south India.

Like the hymnists the Dasakutas has firsthand experience of gods and their grace. The dasas of Karnataka headed by Purandaradasa, followed by Kanaka, Vijaya, Gopala, Vithala Jegannatha and others constitute the Dasakuta. The dasas closely follow the metaphysical tenets of Sri Madhva`s philosophy. The Dasabhava is an approved form of bhakti adumbrated by Sri Madhava. Purandara Dasa has the special title to eminence by virtue of being the pioneer preceptor of Carnatic music. The dasas has awakened spiritual faith in men through the medium of music with examples drawn from mundane life.

The origins of the major composers suggest identification with the Vijayanagara Empire. Purandara Dasa was born near Pune and settled in the capital city of Vijayanagara. It is claimed that he was known to Krishnadevaraya. The valleys of the Krishna River had been the meeting place of Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka

The Tallappakkam composers are hailed as the pioneers of the congregational prayer format from which arose the Nama Siddhanta cult. Favouring bhava (concentration on a mood) as a theme the Nama Siddhanta School brought art into direct contact with religion. A theme of art need not always be religious. This school that gained popularity during the Nayaka period, had not been able to ignore treatment of the religious sentiment of devotion to God (bhakti) and the tranquillity of liberation (santha) in addition to secular feelings like fear (bhayam), love (rathi) and sorrow (soka). Thus art served as a catalytic agent for fostering the religious spirit. This is a special contribution of Vedanta. The goal of religion is the attainment of moksha (liberation). The Sankya philosophy declares that art has no relevance to moksha. Vedanta on the other hand states that art is both a pointer to and preparation for moksha, sreyas and prey as which are antagonistic meet in sangita. Sreyas is that which is immediately pleasant; what is sreyas is not preyas. It is said that music tames the mind and senses. This is another dimension of the art of music. The music of the Nayaka period was believed to have ennobled the soul.