The British in India had to play much dual roles when they were concerned with Indian administration and welfare of the `natives`. On one hand the Raj was busy establishing their domination over the Eastern society by implementing ruthless measures and, on the other hand there were also a few handfuls of Englishmen who did show empathy towards the Indian citizens. The latter was made fruitful in several innovative ways of bringing in western cultural and scientific sources and assimilating them to make India a better place to live in. One such marvellous instance was the building and constructing of bridges across rivers and uncharted lands. History of Indian bridges thus commenced from crucial moments, together with nails, girders, steel and solid plates.

The British in India had to play much dual roles when they were concerned with Indian administration and welfare of the `natives`. On one hand the Raj was busy establishing their domination over the Eastern society by implementing ruthless measures and, on the other hand there were also a few handfuls of Englishmen who did show empathy towards the Indian citizens. The latter was made fruitful in several innovative ways of bringing in western cultural and scientific sources and assimilating them to make India a better place to live in. One such marvellous instance was the building and constructing of bridges across rivers and uncharted lands. History of Indian bridges thus commenced from crucial moments, together with nails, girders, steel and solid plates.

Some of the bridges in particular were unforgettable. They often carried roadways too, the double-track bridge becoming a speciality of British engineering. In many other ways they were boldly innovative, especially in dealing with problems of river flow and sediment. History of Indian bridges quite justifiably began with solemn attempts by the Britons trying to bridge the wide gaps along rivers and mountainous terrain. The bridges did not generally aim at beauty; many of them were built with sophisticated techniques of suspension or cantilever. In their time, though, they were some of the most ambitious and technically interesting in the world.

Aesthetically, too, bridges could be stunning in their power. History of Indian bridges and commencement of building definitely starts with the Attock Bridge across the Indus River. The bridge which took the Punjab Northern State Railway up to Peshawar (presently in Pakistan) and the frontier, was a marvellous spectacle. Completed in 1883 to the designs of engineer Guilford Molesworth, it was built on two decks, the railway crossing above and the Grand Trunk Road below. Attock Bridge was approached through huge iron gates, sentry-boxes and gun-posts. Slowly and carefully the trains eased their way across its exposed upper deck, high above the river.

The gradual development of history of Indian bridges can further be illustrated with the spectacular Lansdowne Bridge over the Indus River at Sukkur. During British times, the bridge was nicknamed as perhaps the ugliest ever built, but also among the most memorable. Sir Alexander Rendel, one of the great bridge-builders of the day, was responsible for the design of this structure. Lansdowne Bridge was opened for thoroughfare in 1889 and was variously described in contradicting terms of good and bad, but with a design in which `the lamp of truth shines with too lurid a flame`. There was something suggestively timeless to the bizarre mass of ironwork by which this edifice carried the Indus Valley State Railway across the river. Two enormous cantilever structures held the weight of the bridge, like a couple of dozen cranes bolted permanently together in thick meshes of struts and girders. Each was 170 feet high and the whole thing then served as the longest cantilever span ever built.

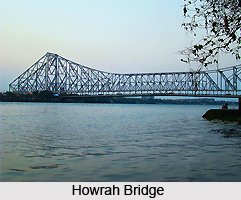

Some of the Indian railway bridges were built on tall wooden trestles. Some, like the ones that carried the trains to Shimla, resembled Roman aqueducts, with piled rows of masonry arches. History of Indian bridges under British Raj seemed like a prolonged stretch of lines, growing together with native population. Some had become so familiar that they became an essential part of the Indian scene. Of the last bunch, the most familiar of all was undoubtedly the Howrah Bridge across the Hooghly River in Calcutta. It did not carry a railway proper, only a tram-line, but it served as the only connection between the main railway termini of the city, one on the east bank of the river, with the west. Engineered by Hubert Shirley-Smith, Howrah Bridge was completed in 1943, replacing a bridge of boats as the only bridge across the river in a city of two million people. It was built in a single cantilever span, approximately 1500 feet long (it stretched some four feet in the heat of every Calcutta noonday, contracting again each evening), and stood so high that it dwarfed all the buildings around it. Quite evidently, Howrah Bridge became at once the popular hallmark of the bustling city.