The Hinayana, "Little Vehicle" or "Lower Way", was so called by the Mahayanists because it teaches the attainment of salvation for oneself alone. It is predominantly ethico-psychological in character and its spiritual ideal is embodied in the austere figure of the Arhant, a person in whom all craving is extinct, and who will no more be reborn. While mindfulness, self-control, equanimity, detachment, and the rest of the ascetic virtues are regarded as in¬dispensable, in the final analysis emancipation (moksha) is attained through in¬sight into the transitory (anitya) and painful (dukkha) nature of conditioned things, as well as into the non-selfhood (nairatmyata) of all the elements of existence (dharmas), whether conditioned or unconditioned. This last consists in the realization that personality is illusory, and that, far from being a sub¬stantial entity, the so-called "I" is only the conventional label for a congeries of evanescent material and mental processes. At the price of complete with¬drawal from all worldly concerns emancipation, or Arhantship, is attainable in this very birth.

The Hinayana, "Little Vehicle" or "Lower Way", was so called by the Mahayanists because it teaches the attainment of salvation for oneself alone. It is predominantly ethico-psychological in character and its spiritual ideal is embodied in the austere figure of the Arhant, a person in whom all craving is extinct, and who will no more be reborn. While mindfulness, self-control, equanimity, detachment, and the rest of the ascetic virtues are regarded as in¬dispensable, in the final analysis emancipation (moksha) is attained through in¬sight into the transitory (anitya) and painful (dukkha) nature of conditioned things, as well as into the non-selfhood (nairatmyata) of all the elements of existence (dharmas), whether conditioned or unconditioned. This last consists in the realization that personality is illusory, and that, far from being a sub¬stantial entity, the so-called "I" is only the conventional label for a congeries of evanescent material and mental processes. At the price of complete with¬drawal from all worldly concerns emancipation, or Arhantship, is attainable in this very birth.

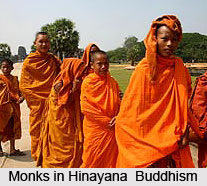

As per the study, the Hinayana insists upon the necessity of the monastic life, with which it tends to identify the spiritual life altogether. The laity simply observes the more elementary precepts, worship the relics of the Buddha, and support the monks, by which means merit or "punya" is accumulated and rebirth in heaven assured. As for the difference between Buddha and Arhant, it is only a matter of relative priority of attainment, and of relative extent of supernormal powers. The most widespread and influential Hinayana school in earlier times was that of the Sarvastivadins, who were greatly devoted to the study and propagation of the Abhidharma. They were later also known as the "Vaibhashikas", the "Vibhasha" being the gigantic commentary on the "Jnatia-prasthana" which had been compiled by the leaders of the school in Kashmir during the first or second century of the Christian era. The contents of the "Vibhasha" are systematized and explained in Vasubandhu"s "Abhidharma-kosa" or "Treasury of the Abhidharma", a work which represents the culmination of Hinayana thought and has exercised enormous historical influence. The com¬mentary incorporates "Sautrantika" views, thus not only bridging the gap between the Hinayana and the Mahayana but paving the way for Vasuban¬dhu"s own conversion to the latter "yana".

Infact, the Mahayana, literally "Great Vehicle" or "Great Way", is so called because it teaches the salvation of all. Predominantly devotional and meta¬physical in character, its ideal is the Bodhisattva. The Bodhisattva is considered as the heroic being who, practising the six or ten Perfections (paramita) throughout thousands of lives, aspires to the attainment of Buddhahood for the sake of all conscious beings. Perspectives infinitely vaster than those of the Hinayana are here disclosed.

In the Mahayana Arhantship, far from being the highest achievement is only a stage of the path. As per this belief, the true goal is Supreme Buddhahood. This stage cannot be reached simply by overcoming one"s passion. Rather it is through (pudgala-nairatmya) or by perceiving non-selfhood and "jneyavarana" that a person can achieve this stage. Hinayana propagates that human beings are dharma-nairatmya, that is, they do not have selfhood and are unreal. On the contrary it is merely the thought process of the humans that define them as real. In this radical manner the Mahayana Buddhism reduces all possible objects of experience, whether internal or ex¬ternal, to the Void (Sunyata), which is not a state of non-existence or privation but rather the ineffable non-dual Reality. The Void transcends all apparent oppo¬sitions, such as being and non-being, self and others, Samsara and Nirvana Expressed in more positive terms, all things exist in a state of "suchness" or "thusness" and, since this is one "suchness", also in a state of sameness or "samata".