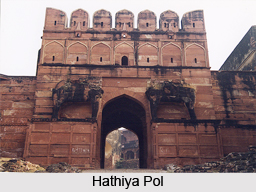

Fatehpur Sikri absolutely and perfectly redefines enormity, gargantuan, massiveness and red sandstone build tremendous edifice that was once utilised by Akbar as his imperial residence. Fatehpur Sikri in its all sensuousness and classic `reddish` appearance stands to this day as par excellence to any of the historic or pre-historic forts that can still be witnessed in India. Incorporating minute detailed wings, kilometres of architectural masterpieces and looking deep into everybody`s benefit, Fathepur Sikri stood as Emperor Akbar`s badge of Mughal masterpiece, overlooking the village of Sikri. Encompassing thousands of legends, as can be associated with such magnificent and magnanimous Mughal construction, the garh (implying a fort) could be entered from all the four cardinal corners, with each entrance gate demanding meticulous attention as to its splendorous embellishment. Besides the now-majestic Buland Darwaza, the Hathiya Pol in Fatepur Sikri is one more specialised entranceway, which has with time necessitated praise, admiration and honour. Just can be precedented, Hathiya Pol also possesses its own share of legends and architectural pains, to lend life to such a conception.

Fatehpur Sikri absolutely and perfectly redefines enormity, gargantuan, massiveness and red sandstone build tremendous edifice that was once utilised by Akbar as his imperial residence. Fatehpur Sikri in its all sensuousness and classic `reddish` appearance stands to this day as par excellence to any of the historic or pre-historic forts that can still be witnessed in India. Incorporating minute detailed wings, kilometres of architectural masterpieces and looking deep into everybody`s benefit, Fathepur Sikri stood as Emperor Akbar`s badge of Mughal masterpiece, overlooking the village of Sikri. Encompassing thousands of legends, as can be associated with such magnificent and magnanimous Mughal construction, the garh (implying a fort) could be entered from all the four cardinal corners, with each entrance gate demanding meticulous attention as to its splendorous embellishment. Besides the now-majestic Buland Darwaza, the Hathiya Pol in Fatepur Sikri is one more specialised entranceway, which has with time necessitated praise, admiration and honour. Just can be precedented, Hathiya Pol also possesses its own share of legends and architectural pains, to lend life to such a conception.

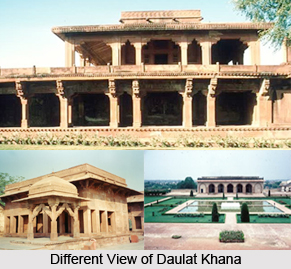

The Hathiya Pol, or Elephant gate, as is translated from Mughal Urdu into colloquial English, is situated at the southern end of the Fatehpur Sikri palace complex. Although Fatehpur was basically lent a design, that appears as a fort to every normal eye, it was basically employed and utilised as a palatial and pleasure and business and cultural complex by Akbar during most prime ruling period. As such, Fatehpur Sikri was re-named as a palace complex by the Mughal Emperor himself. Hathiya Pol was, in all probability legendary as the imperial entrance. Highly unlike the Buland Darwaza, which was chiselled to commemorate a victory and which was basically the gateway to the rest of the world, Hathiya Pol was rather humble in its appearance to its venerated and awing cousin. The Hathiya Pol in Fatehpur Sikri primarily consisted by its flanking sides, a naqqar khana, or chamber where ceremonial drums were played. The view towards this southern entrance is incredibly imposing, almost as spectacular as that toward the powerful Buland Darwaza on the north. In front of the Hathiya Pol, there can be witnessed a large serai (a rest house for travellers and caravans, prevalent during the Mughal era). Beyond the gate, the chattris and roofs of the palaces are still very much visible to one`s admiration and emancipation. Once one enters this southern gate, there is access to both the mosque complex (referring to the Jama Masjid housed within) and the palace structures, including the Daulat Khana-i Khas o Amm and the Diwan-i-Am or Public Audience Hall - one of the most important and decisive administrative units.

It is quite a recognised fact that every Indian fort possesses an entrance associated with elephants, which was a kind of demonstrating respect and panache and also exploring the universality of the royal household, irrespective of Hindus and Muslims. As such, elephant entryways probably were intended for the entry of palanquined elephants, in India, long considered the imperial mount. For Akbar, moreover, elephants appear to have had held a special importance, which could only access through the Hathiya Pol. His reverence for these animals is discussed by Abu ul-Fazl, the official and legendary chronicler to Akbar`s court, who notes that elephants can only be controlled by wise and intelligent men, a man as Akbar was. In the illustrated Akbar Nama in the Victoria and Albert Museum (in London), generally conceived to have been Akbar`s personal copy, elephants are frequently depicted and on several pages there are illustrations of Akbar controlling mad elephants - elephants that no other mortal could ride! As the emperor once had indicated to Abu ul-Fazl, successfully riding such a beast without being killed should be taken as a sign of God`s contentment with him. From such inspiring and exalting information about his mystery Mughal man, acknowledged as `Akbar the Great`, it can very well be comprehended that Hathiya Pol had held sublime signification to the emperor himself, which also included his courtiers and well-wishers.

At the foot of the rampart leading to the Hathiya Pol in Fatehpur Sikri, there can gallantly be witnessed a minaret, spiked with stone projections, resembling elephant tusks. Popularly acknowledged as the Hiran Minar and deemed a hunting tower, this however is not mentioned in any contemporary Mughal-referred texts. This tower, derived from Iranian prototypes, was probably utilised to indicate the starting point for subsequent mile posts (kos minar). During Mughal India, such mile posts were conceived as conical-shaped smooth-faced minarets; umpteen such presently remain between Agra and Delhi, as well as in other areas of north western India and Pakistan. The tusk-like shape of the protruding stones in Hiran Minar appears appropriate for this tower`s location near the Elephant gate Hathiya Pol and may be yet one more reference to Akbar as controller of elephants and ultimately of the well-administered state.

To the west of the Hathiya Pol Elephant gate, exists an enormous quadrangular courtyard, historically acknowledged as the Public Audience Hall or Diwan-i-Am. It is one of the few areas within the palace whose function is certain to present-day reference Mughal texts. The road leading from the Elephant gate walls to this audience hall was once lined with shops and markets that were commenced in 1576-77. Indeed, Fatehpur Sikri is so huge in its plan and building, that during Mughal era, especially after Akbar, it had contained within itself an entire city enclosed within high walls, just as properly functioning like any other city, outside the purview of Fatehpur. The Diwan-i-Am is a focal point of the palatial Fatehpur Sikri complex, a secular one at that, complementing the mosque complex of Jama Masjid. The rest of the palace lay between the mosque and audience hall, pivotal points which reflects Akbar`s concerns with religion and the welfare of the state.