Gold Art in Mughal Empire were particularly at risk because of their higher intrinsic value. Historical records say that in India still there are a lot of Mughal decorative arts in gold. Gold Art in Mughal Empire is known for the innumerable jewellery. Besides there are also the throne of Muhammad Shah, a rose water sprinkler and a gold ovoid box encrusted with rubies and emeralds. Gold Art includes octagonal box of gold, covered with white enamel - like the pandans with matching trays in plates. An engraved gold spoon set with rubies, emeralds and diamonds displays the restrained elegance with which objects were fashioned for Akbar, the Great. There is little emphasis in the design on the intrinsic worth of the gems, so unlike the glitter of Ottoman pieces which loudly proclaim the bulging coffers of the Sultans.

Gold Art in Mughal Empire were particularly at risk because of their higher intrinsic value. Historical records say that in India still there are a lot of Mughal decorative arts in gold. Gold Art in Mughal Empire is known for the innumerable jewellery. Besides there are also the throne of Muhammad Shah, a rose water sprinkler and a gold ovoid box encrusted with rubies and emeralds. Gold Art includes octagonal box of gold, covered with white enamel - like the pandans with matching trays in plates. An engraved gold spoon set with rubies, emeralds and diamonds displays the restrained elegance with which objects were fashioned for Akbar, the Great. There is little emphasis in the design on the intrinsic worth of the gems, so unlike the glitter of Ottoman pieces which loudly proclaim the bulging coffers of the Sultans.

Equally discreet is the gold vase with a domed cover embellished with dark green enamel for the background, and white enamel for the flowers which are enclosed in a trellis design. Unusual mango-hued enamel joins them on the neck and shoulder to represent the centres of the narcissi, and the blossoms on the lid are painted in pink. These colours and patterns remind us of the brilliant but sadly damaged unpublished tiles of the shrine of Shaykh Bakhtiyar Kaki at Mehrauli, south of Delhi, refurbished by Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb. The overall shape of this piece has no parallel in India; it may have been inspired by a Timurid jug owned by the emperor.

Gold pandan is also famous art craft of Gold Art in Mughal era. The three surfaces are engraved to form the radiating petals of great, full-blown lotuses. The exterior of the box and its matching tray present a bustling mass of flowering plants, clearly meant to resemble rubies and emeralds.

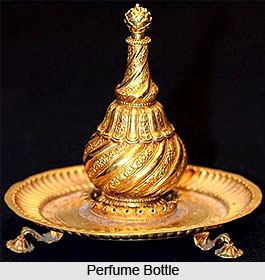

Another gold pandan and matching tray of the Mughal era combines the techniques of champleve and cloisonn‚ enamel. A similarly conceived polygonal gold pandan on a tray is depicted in a painting where it lies at the feet of a young Mughal prince enjoying a cooling bath at the side of a well. His radiance is enhanced by a Timurid halo exactly like the one often favoured by Jahangir in his portraits: an effulgent solar disk combined with a crescent moon at the bottom. As beautiful country girls serenade him and shower him with jewels - a compliment no doubt to his charms a round huqqa on a ring is noted around him, a small spittoon, a low table, perfume bottles, a lidded cup, rose water sprinklers and various rope rings used by village girls for carrying water pots on their heads, the ancestors of the rings placed beneath huqqas.

Another gold pandan and matching tray of the Mughal era combines the techniques of champleve and cloisonn‚ enamel. A similarly conceived polygonal gold pandan on a tray is depicted in a painting where it lies at the feet of a young Mughal prince enjoying a cooling bath at the side of a well. His radiance is enhanced by a Timurid halo exactly like the one often favoured by Jahangir in his portraits: an effulgent solar disk combined with a crescent moon at the bottom. As beautiful country girls serenade him and shower him with jewels - a compliment no doubt to his charms a round huqqa on a ring is noted around him, a small spittoon, a low table, perfume bottles, a lidded cup, rose water sprinklers and various rope rings used by village girls for carrying water pots on their heads, the ancestors of the rings placed beneath huqqas.

Three gold enamelled dishes, also part of Nadir Shah`s booty, are costlier versions of the dramatic bidri trays. These are of modest size, averaging slightly more than 19 cm in diameter. One is strewn with concentric rows of red carnations against a plain gold ground; another has a brilliant tangle of red poppy plants around a central lotus. The third is the most dramatic of all: a single giant lotus fills the entire field, using this favourite Indian flower just like the monumental stone lotus roundels at the ancient Buddhist Sanchi Stupa and Amaravati from two thousand years before. These flowers were symbols of Bodhisattvas, pure beings who, unsullied by the filth of the world, chose to remain in it to inspire less advanced creatures, just like lotus flowers whose beauty is undimmed by the mud of the swamp in which they grow. Such Hindu and Buddhist motifs were still very much alive in Mughal India, although we can hardly suppose their ancient meanings had survived.

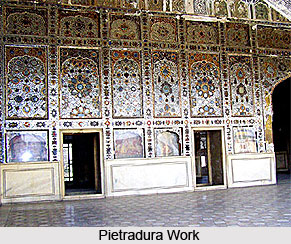

A slightly larger gold dish of the Mughal Era far surpasses the impact of the last three. Against white enamel, spinels and emeralds form flower-heads of convincing weight and volume, contrasting with the unenamelled gold surface of the centre. These gem-studded poppy plants, swaying to the gentlest of rhythms, give an effect of such potent and severe classicism that one is tempted to see the plate in the old Indian tradition of a great abstract mandala, a tool if not for meditation then at least for the most lyrical reverie. Its amazing quality puts it into a class well above most other Mughal objects, more akin to the finest carved marble dados or pietra-dura work in Mughal palaces. In fact, the plate`s milky white enamel is analogous to the fashion for white marble architecture popularised by Shah Jahan (1628-58), and must fall into his reign and circle.

A gold spice box is also noteworthy in the Mughal era. Its off-white enamel is merely speckled, lacking the finesse of the other; its flowers have much more dash. On the bottom, parrots squawk and nibble flowers; on the lid, floppy lilies perform a mad dance beneath a ruby finial. Poppies and lilies on the sides jostle each other like viewers at some spectacle. Lightly drawn, minute gold V-shapes give the effect of far-off birds soaring in the sky, making the decidedly short flowers seem monumental.

A gold spice box is also noteworthy in the Mughal era. Its off-white enamel is merely speckled, lacking the finesse of the other; its flowers have much more dash. On the bottom, parrots squawk and nibble flowers; on the lid, floppy lilies perform a mad dance beneath a ruby finial. Poppies and lilies on the sides jostle each other like viewers at some spectacle. Lightly drawn, minute gold V-shapes give the effect of far-off birds soaring in the sky, making the decidedly short flowers seem monumental.

A huqqa ring of the Mughal period has an earthier air, appropriate to its function of stabilising another object: a large round matching huqqa would have been placed upon it while being smoked. Outside, butterflies and dragonflies hover over large red poppies, while inside powder-blue and yellow serrated leaves descend towards the (missing) huqqa. These tones, so different from those of the other enamelled pieces, suggest a different provenance within India, perhaps Rajasthan.

Unadorned gold provides the background for an ecstatic vision of three angels bearing celebratory vessels, alternating with birds in full flight and full-blown white lotuses, the whole enclosed in a graciously unfolding meander of creepers and flowers. The variety of brilliant colours, carefully chosen to harmonise, the sensitively drawn designs and the perfectly balanced composition establish a mood of rapture where we would expect mere luxury. The nuances of colour are surprisingly subtle: several shades of blue, from pale lilac to deep royal blue; several shades of green, yellow and white; and a unique sherry-like tan on the wings of the birds and angels. The facial types of the angels, their costumes and turbans, and the peculiar swing of their skirts and sashes are exactly those of figures in early eighteenth-century Mewar paintings.

It can be said about Golden Art in Mughal Empire that serenity is sought and the values of artistry prevail over brash displays of wealth. The surface of each piece is so densely packed with stones in such narrow, masterfully worked settings that potential visual jolts are minimised.

The great gold throne in the Topkapi is one of the most significant vestiges of Mughal India. It is of the bed-like, platform type favoured in the subcontinent, with a back-rest in the elegantly cusped Chinese cloud-collar form. Its low parapets resemble the low walls on Indian palace terraces, with horizontal panels alternating with uprights crowned with fruit-like finials - here, all rubies set in gold. The panels themselves bear extraordinary enamelling in red, dark green and unusual chartreuse, set with jewelled flowering plants and arabesques. The feet are splendidly robust, shortened versions of the familiar Mughal baluster pillar. The whole is of such impeccable quality, costliness of materials and harmony of design that there can be no doubt that this throne is one of the royal pieces sent to Istanbul by Nadir Shah - probably the very throne used by the unfortunate

Emperor Muhammad Shah.

Also at Powis is a remarkable bit of decorative sculpture: a small tiger head of gold on a wooden core, set with rubies, diamonds and emeralds, some of the jewels imitating tiger stripes.