Introduction

Brahmaputra River is one of the largest rivers in India as well as in Asia. The meaning of the name Brahmaputra in Sanskrit language is `The Son of Brahma`. The river flows in India and its neighboring countries namely, Bangladesh and China. In the Indian subcontinent, it flows through the dense forests and tribal settlements.

Brahmaputra River is one of the largest rivers in India as well as in Asia. The meaning of the name Brahmaputra in Sanskrit language is `The Son of Brahma`. The river flows in India and its neighboring countries namely, Bangladesh and China. In the Indian subcontinent, it flows through the dense forests and tribal settlements.

History of Brahmaputra River

The Brahmaputra River is one of the great rivers of Asia. The history of Brahmaputra River starts its 3,000-km journey to the Bay of Bengal from the slopes of Kailash in western Tibet. As Tibet`s great river, the Tsangpo, crosses from east to the high-altitude Tibetan plateau north of the Great Himalayan Range, carving out myriad channels and sandbanks on its way. As it tumbles from the Himalayan heights towards the plains of the subcontinent it meanders back on itself, cutting a deep and still unnavigated gorge, until finally turning south it emerges in Arunachal Pradesh as the Dihong. Just beyond Pasighat, it meets the Dibang and Lohit where it finally becomes the Brahmaputra.

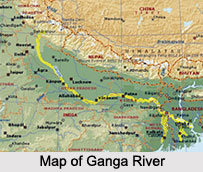

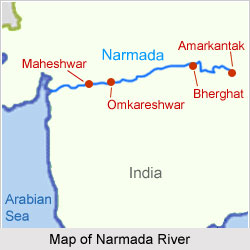

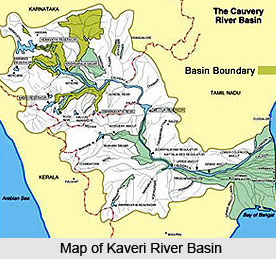

As the rivers Dibang and Lohit join the Siang, it gets the name of Brahmaputra and flows into Assam. Brahmaputra is to Assam what the Ganges is to the northern part of India and Kaveri is to the south. Coming down from a place called Sadiya, south of Arunachal Pradesh, the Brahmaputra passes through Dibrugarh, Neamati, Tezpur, Guwahati, and finally joins Padma, the easternmost tributary of the Ganges. This joined stream then flows into Bangladesh where it merges with river Meghna, one of the most significant estuaries of the Ganges. The Brahmaputra valley is closely related with lores from the great Indian epic Mahabharata and with Shaivite traditions or the worship of Lord Shiva, the destroyer in the Hindu pantheon.

As the rivers Dibang and Lohit join the Siang, it gets the name of Brahmaputra and flows into Assam. Brahmaputra is to Assam what the Ganges is to the northern part of India and Kaveri is to the south. Coming down from a place called Sadiya, south of Arunachal Pradesh, the Brahmaputra passes through Dibrugarh, Neamati, Tezpur, Guwahati, and finally joins Padma, the easternmost tributary of the Ganges. This joined stream then flows into Bangladesh where it merges with river Meghna, one of the most significant estuaries of the Ganges. The Brahmaputra valley is closely related with lores from the great Indian epic Mahabharata and with Shaivite traditions or the worship of Lord Shiva, the destroyer in the Hindu pantheon.

Every few yards there is a ruin or a site that brings legendary associations with it. One site, which is considered very holy, is the Kamakhya temple, about 2 km from the banks of the Brahmaputra, near Guwahati. It is believed that if one do not go up the steps leading to this temple of feminine power, Shakti, or the other half of Shiva, he will be made to cross the Brahmaputra seven times. That was quite a threat, for the Brahmaputra is not a quiet river that lets you pass easily. In fact, there are expanses that are so dangerous that locals believe a monster lives in those patches. Every year that monster takes a toll on the human life as boats overturn or floods swallow the neighboring lands.

Brahmaputra River has its history of flow through the dense forests and tribal settlements. A seldom-run river, the Brahmaputra offers beautiful scenery, excellent big white water and great wild life in a less-visited corner of the sub-continent. The Brahmaputra has its source at holy Mount Kailash Mansarover in Tibet, traverses the entire Tibetan plateau, and then makes its great bend into India, cutting into the Himalaya the deepest canyon in the world, a canyon which has as yet dodged away all attempts at exploration.

The various adventurous sports held in the Brahmaputra River have helped the India`s poor high-end adventure reputation to be changed. The experienced crew of rafters and kayakers has put together a rafting expedition down the mighty Brahmaputra. In the History of Brahmaputra River, this 180-km stretch of water will mark the first non-military expedition on the river and the first commercial foray in the politically susceptible region.

Origin of Brahmaputra River

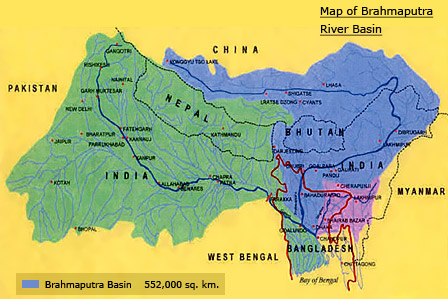

Origin of Brahmaputra River is in south-western Tibet as the Yarlung Tsangpo River. Brahmaputra River is one of the largest rivers in Asia. The total length of the river is about 2900 km. The river takes birth at the Mansarovar of the Himalayas, flows through Tibet, China, Burma, India and joins with River Ganga in Bangladesh. It flows across south-western Tibet and then it breaks through the Himalayas in great gorge. Its basin covers the areas of Tibet, China, India and Bangladesh. It is a trans-boundary river.

Origin of Brahmaputra River is in south-western Tibet as the Yarlung Tsangpo River. Brahmaputra River is one of the largest rivers in Asia. The total length of the river is about 2900 km. The river takes birth at the Mansarovar of the Himalayas, flows through Tibet, China, Burma, India and joins with River Ganga in Bangladesh. It flows across south-western Tibet and then it breaks through the Himalayas in great gorge. Its basin covers the areas of Tibet, China, India and Bangladesh. It is a trans-boundary river.

Etymology of Brahmaputra River

Brahmaputra River is also called "Tsangpo-Brahmaputra". In Tibet, the Brahmaputra River is known as "Yarlung Tsangpo River". In Arunachal Pradesh, it is known as "Dihang", in the Assam Valley as "Brahmaputra", in Bangladesh as the "Jamuna" and "Meghna" before emptying into the Bay of Bengal. The Sanskrit name for Brahmaputra is "Lauhitya". The word Brahmaputra means "Son of Brahma" and according to the Hindu mythology, it is a holy river. The biggest and the smallest river islands in the world are Majuli and Umandana which are formed along this river.

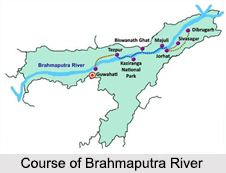

Course of Brahmaputra River in India

Course of Brahmaputra River in India

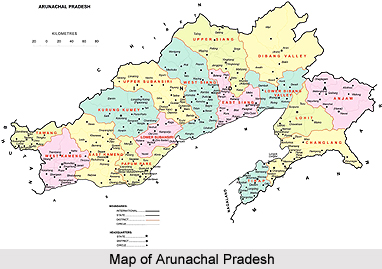

Brahmaputra River enters India in the far north-eastern state of Arunachal Pradesh after travelling hundreds of miles over Tibet as the Tsangpo from its birthplace near the holy lake of Mansarovar. It is one of the world"s largest rivers, on the similar scale with the Indus, Mississippi and the Nile.

From its origin in south-western Tibet as the Yarlung Tsangpo River, it flows across southern Tibet to penetrate through the Himalayas in great gorges and into Arunachal Pradesh, flows south-west through the Assam Valley and then towards south through Bangladesh. There it converges with the River Ganga to form a vast delta. In Bangladesh, the river merges with the Ganga and divides into two the Hooghly River and Padma River. When it merges with the Ganges, it forms the world`s largest delta at the Sunderbans and finally empties into the Bay of Bengal.

The upper course of Brahmaputra River was unknown for a long time, and its identity with the Yarlung Tsangpo was only recognized by exploration in 1884-86. The lower reaches are sacred among the Hindus. Brahmaputra River is navigable along most of the river length. The river is prone to catastrophic flooding in spring when the Himalayan snows melt. It is also one of the few rivers in the world that exhibit a tidal influence.

Geology of Brahmaputra River

After the origin of Brahmaputra River in southwestern Tibet as the Yarlung Tsangpo River, it flows across southern Tibet to penetrate through the Himalayas in great canyons and into Arunachal Pradesh where it is known as Dihang River. The Brahmaputra River flows southwest through the Assam Valley as Brahmaputra and south through Bangladesh as the Jamuna. There it gets together with the Ganga to form an enormous delta. The river is almost 1,800 mi (2,900 km) in length and is an important source for irrigation and transportation. Its upper course was long unknown, and its identity with the Yarlung Tsangpo was only established by discovery in 1884-86. This river is often called Tsangpo-Brahmaputra River. In Bangladesh the river flows together with the Ganga and splits into two the Hugli and Padma River. When it merges with the Ganges it forms the world`s largest delta, called the Sunderbans. The Sunderbans is best known for its tigers and mangroves. This river has a rare male name that means "son of Brahma" in Sanskrit.

After the origin of Brahmaputra River in southwestern Tibet as the Yarlung Tsangpo River, it flows across southern Tibet to penetrate through the Himalayas in great canyons and into Arunachal Pradesh where it is known as Dihang River. The Brahmaputra River flows southwest through the Assam Valley as Brahmaputra and south through Bangladesh as the Jamuna. There it gets together with the Ganga to form an enormous delta. The river is almost 1,800 mi (2,900 km) in length and is an important source for irrigation and transportation. Its upper course was long unknown, and its identity with the Yarlung Tsangpo was only established by discovery in 1884-86. This river is often called Tsangpo-Brahmaputra River. In Bangladesh the river flows together with the Ganga and splits into two the Hugli and Padma River. When it merges with the Ganges it forms the world`s largest delta, called the Sunderbans. The Sunderbans is best known for its tigers and mangroves. This river has a rare male name that means "son of Brahma" in Sanskrit.

The Brahmaputra is navigable for most of its length because of its favorable geological properties. The lower part of this river is sacred to Hindus. The river is prone to disastrous flooding in spring when the Himalayan snows melt. It is also one of the few rivers in the world that is prone to tides.

Late Quaternary sediments of the Brahmaputra basin bear a history of river switching, climate change as revealed from sand- and clay-size mineralogy of boreholes, and modern riverbed grabs. Epidote to garnet ratios in sand fraction sediments is diagnostic of source with high E/G that indicates Brahmaputra origin and low E/G indicates Ganges prominence. The Brahmaputra contains kaolinite (29%), illite (63%), and chlorite (3%).

The analysis of mineralogic and stratigraphic data of Brahmaputra basin indicates that the Ganges and Brahmaputra rivers have changed position several times during the Holocene. Extended periods of mixed river inputs seem to be out-of-the-way to the Early Holocene, indicating quick migrating and meandering channels during sea level low stand. Tectonically shifted accommodation in the Sylhet Basin may have contributed to the superior easterly course of the Brahmaputra during much of the Holocene.

The abundances of illite and chlorite as in comparison to smectite and kaolinite suggest varied degrees of physical and chemical weathering. High IC values in early post-glacial deposits in the Brahmaputra river course, suggest a dominance of physical weathering during that time. Enhanced chemical weathering under increasingly warmer and more humid conditions are also due to various geological changes in the basin. Weathering patterns in the catchment respond quickly to climatic shifts has similar reasons.

Geography of Brahmaputra River

The Brahmaputra River is one of the major rivers in Eastern India. During the monsoon season or the months of June-October, floods seem to be a common occurrence in the geographical area of Brahmaputra River. Deforestation in the Brahmaputra watershed has resulted in increased siltation levels that result in flash floods, and soil erosion in critical downstream habitat, such as the Kaziranga National Park in middle Assam. Occasionally, massive flooding causes huge losses to crops, life and property. Periodic flooding is a natural phenomenon that is economically important because it helps to maintain the lowland grasslands and associated wildlife. Periodic floods also deposit fresh alluvium refilling the fertile soil of the Brahmaputra River Valley. Thus flooding, agriculture and agricultural practices are closely connected.

The Brahmaputra River is one of the major rivers in Eastern India. During the monsoon season or the months of June-October, floods seem to be a common occurrence in the geographical area of Brahmaputra River. Deforestation in the Brahmaputra watershed has resulted in increased siltation levels that result in flash floods, and soil erosion in critical downstream habitat, such as the Kaziranga National Park in middle Assam. Occasionally, massive flooding causes huge losses to crops, life and property. Periodic flooding is a natural phenomenon that is economically important because it helps to maintain the lowland grasslands and associated wildlife. Periodic floods also deposit fresh alluvium refilling the fertile soil of the Brahmaputra River Valley. Thus flooding, agriculture and agricultural practices are closely connected.

The Indo-Gangetic Plains along the Brahmaputra River are large floodplains of the Indus and the Ganga-Brahmaputra river systems. They run parallel to the Himalayan mountain ranges and extend from the Jammu and Kashmir in the northwest to Assam in the east. Some of the main rivers like Ganga and Indus are an integral part of Indian geography. The Geography of India extends from the Deccan Plateau and is a part of the Central Highlands, which comprises, besides Deccan Plateau, in the south, Malwa Plateau, in the west, and Chota Nagpur Plateau in the east. The fertile plain of Brahmaputra is a flat plateau covering vast acres of land with elevations ranging from 300 to 600 m. It is bounded by mountain ranges to the north and flanked by other vegetations.

Brahmaputra River one of the largest rivers in the world and its basin covers areas in Tibet, China, India and Bangladesh. It originates in the Chemayung-Dung glacier, approximately at the location of some 145 km from Parkha, an important trade centre between lake Manasarowar and Mount Kailas. It has a long course through the dry and flat region of southern Tibet before and then it breaks through the Himalayas near the Namcha Barwa peak at about 7,755m. Its main tributaries in India are the Amochu, Sankosh, Dibang, Raidak, Bhareli, Mans and Luhit. The several tributaries in Tibet are resulting partly from a low range between the main Himalayas and the Tsang-po. The total length of the river from its source in southwestern Tibet to the mouth in the Bay of Bengal is around 2,850 km, including the Padma and Meghna rivers up to the mouth. Within Bangladesh territory, Brahmaputra-Jamuna is 276 km Long River, of which Brahmaputra is only 69 km.

Course of Brahmaputra River

Brahmaputra flows some 2,900 kilometres from its source (Manasarovar Lake region, near Mount Kailash, on the northern side of the Himalayas in Tibet) to its confluence with River Ganges. It flows along southern Tibet to break through the Himalayas and then into Arunachal Pradesh (India). It flows through the Assam Valley as Brahmaputra and in the south through Bangladesh as the Jamuna River (not to be mistaken with Yamuna of India). In the Ganges Delta, it merges with the Padma, the name of the Ganges river in Bangladesh, and after merging with Padma, it becomes Meghna, before emptying into the Bay of Bengal.

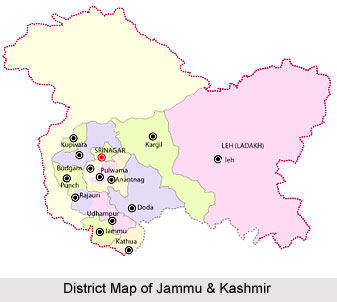

Course of Brahmaputra River in Tibet

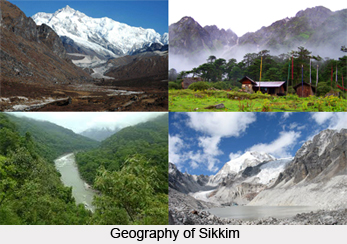

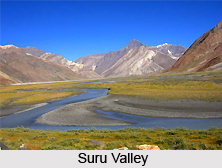

The Brahmaputra river course in Tibet signifies its origin or the upper course. The Yarlung Tsangpo or Brahmaputra River originates in the Jima Yangzong glacier near Mount Kailash in the northern Himalayas. It then flows east for about 1700 km, at an average height of 4000 m, and is thus the highest of the major rivers in the world. From its source, the river runs for nearly 1,100km in an easterly direction between the main range of the Himalayas to the south and the Kailash Range to the north. At its easternmost point, the river bends around Mt. Namcha Barwa, and forms the Yarlung Tsangpo Canyon, which is considered the deepest in the world. During that stretch, the river enters northern Arunachal Pradesh state in India, where it is known as the Dihang or Siang River.

Course of Brahmaputra River in India

River Brahmaputra in India starts from the Arunachal Pradesh. The river enters Arunachal Pradesh and is called Siang and makes a very rapid descend from its original height in Tibet, and finally appears in the plains, where it is called Dihang. It flows for about 35 km and is joined by two other major rivers like Dibang and Lohit. From this point of convergence, the river becomes very wide and is called Brahmaputra. it then enters the state of Assam, and becomes wider. The Jia Bhoreli joins the river in Sonitpur District. At this joint, the river is known as the Kameng River. This river flows across the entire stretch of Assam.

Between the districts of Dibrugarh and Lakhimpur, the river gets divided into two channels; the northern Kherkutia channel and the southern Brahmaputra channel. The two channels join again at about 100 km downstream forming the Majuli Island. At Guwahati near the ancient pilgrimage centre of Hajo, the Brahmaputra penetrates through the rocks of the Shillong Plateau, and is at its narrowest at 1 km bank-to-bank. Because the Brahmaputra River is the narrowest at this point, the Battle of Saraighat was fought here thus giving it a historical importance. The first rail-cum-road bridge across the Brahmaputra was kept to traffic in April 1962 at Saraighat. The old Sanskrit name for the Brahmaputra river is Lauhitya and the local name in Assam is Luit. The native inhabitants, i.e., the Bodos called the river Bhullam-buthur. This term means `making a gurgling sound`. The term was later sanskritised into Brahmaputra.

Course of Brahmaputra River in Bangladesh

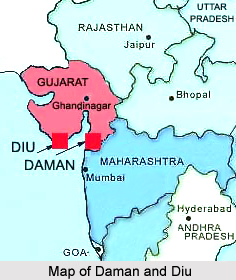

In Bangladesh, the Brahmaputra is joined by the Teesta River, one of its largest tributaries. After this, Brahmaputra River in Bangladesh splits into two branches. The much larger division continues due south as the Jamuna and flows into the Lower Ganges, locally called Padma, while the older branch curves southeast as the lower Brahmaputra and flows into the Meghna. Both rivers eventually reconverge near Chandpur in Bangladesh and flow out into the Bay of Bengal. However, the actual Brahmaputra River in Bangladesh crosses through the Jamalpur and Mymensingh district. The waters of the Ganges and Brahmaputra feed these rivers. This river system forms the Ganges Delta, which is the largest river delta in the world.

When compared to the other major rivers of India, the Brahmaputra is less polluted. However there have been problems arising. The petroleum-refining units contribute most of the industrial pollution load into the basin. Other medium and small industries too pollute the river to some extent. The main problem facing the river basin is that of constant flooding. Floods have been happening more often in recent years. Deforestation and other human activities have also increased to great extent.

Religious Importance of Brahmaputra River

The Brahmaputra is one of the major rivers of Asia possessing mythological importance. The term " Brahmaputra" means "son of Brahma" in Sanskrit. It originates from Mount Kailash in the Himalayan Mountains in western Tibet, passes through China and then flows for 2900kms into the sea in the Bay of Bengal in Bangladesh. It is called Tsangpo in Tibet, Luit or Brahmaputra in Assam, Siang or Dihang in Arunachal Pradesh and one of its main branches is called Jamuna in Bangladesh. Another term for this river in Sanskrit is the Lauhitya. The Bodos call this river Bhullumbutter.

Mount Kailash, the origin of Brahmaputra River is the abode of Lord Shiva and goddess Parvati. The lands and towns along the Brahmaputra River thus attain mythological importance along with the rivers. Koppa Temple at Mansarovar Lake is one of the major visiting spots. Mt. Kailash is claimed to be the summit of the Hindu religious axis, is also one of the highest mountains in Tibet at 22,022 feet. Lord Shiva resides over here among the peaceful Himalayas.

Mount Kailash, the origin of Brahmaputra River is the abode of Lord Shiva and goddess Parvati. The lands and towns along the Brahmaputra River thus attain mythological importance along with the rivers. Koppa Temple at Mansarovar Lake is one of the major visiting spots. Mt. Kailash is claimed to be the summit of the Hindu religious axis, is also one of the highest mountains in Tibet at 22,022 feet. Lord Shiva resides over here among the peaceful Himalayas.

A legendary story says that Lord Shiva once built a house for himself but gave it away to a follower who asked for it. Thus without changing his residence he settled in the mountain of Kailash. This is his abode where he stays with his whole family including his wife Goddess Parvati and children Lord Ganesha and Lord Kartikeya and the other Shiv Ganas like Nandi and others. According to ancient religious texts, the abode of Lord Vishnu is called Vaikuntha, the abode of Lord Brahma is called Brahamaloka and the abode of Lord Shiva is called Kailash. The Brahmaputra River originates from the Kailash. Of the three, one can only go bodily and return in this life from Kailash having experienced spirituality. The Hindus, Bons and Jains all travel to this place as pilgrims. A journey to Kailash along River Brahmaputra is considered as once in a lifetime accomplishment.

It is because of Kailash - Manasarowar, the river Brahmaputra is considered a religious or holy river. The Manasarowar Lake is 865-kms from Delhi, that Kumaon is sometimes called "Manaskhand". Many myths are associated with this unusual mountain and lake and its flowing river. The Buddhists, the Jains and the Bonpas of Tibet too, all respect this river with great fervor and devotion. Therefore, it is not surprising for a devotee to come across the worlds. The Bonpas make an anti-clockwise pilgrimage around Mt. Kailash after a short worship to River Brahmaputra, whereas the believers of the Jain faith specially visit astpaad near the southern region of Kailash in the Kailash --Mansarover region.

Among the thousands of deities of Hinduism, Lord Shiva is the most beloved and the most sought after lord. Lord Shiva finds a great place in the heart of all devotees be it the Human beings, the Devataas or the Rakshasaas and he is directly related to the River Brahmaputra. He is even called Bhola Baba because of his uniqueness of being simple and he grants whatever the devotee asks for. This is the reason why he is having a large number of devotees in all the 3 worlds of Akash, Bhumi, & Patal. Bhola Baba filled with Vairagya or dispassion is a joy of all spiritual seekers.

Divinity is initiated in "Kailash Manasarowar Yatra" along the River Brahmaputra. Many conducted tour packages are available including these spots of religious importance. The most dominant temple is the `Pashupatinath` with many others that are equally significant temples are of great merit along the towns of this river. This primordial temple enshrines faith of millions of Hindus throughout the world as Lord Shiva`s sacred residence. A spiritual atmosphere is carried out throughout the religious trip of River Brahmaputra.

Transportation and navigation of Brahmaputra River

Until Indian independence in 1947, the Brahmaputra River was used as a chief waterway. After the 1990s, the river stretch between Sadiya and Dhubri in India was stated as National Waterway No.2, and it provides services for goods transportation. Recent years have encountered a modest spurt in the growth of river cruises with the advent of the cruise ship, "Charaidew", provided by the Assam Bengal Navigation.

Until Indian independence in 1947, the Brahmaputra River was used as a chief waterway. After the 1990s, the river stretch between Sadiya and Dhubri in India was stated as National Waterway No.2, and it provides services for goods transportation. Recent years have encountered a modest spurt in the growth of river cruises with the advent of the cruise ship, "Charaidew", provided by the Assam Bengal Navigation.

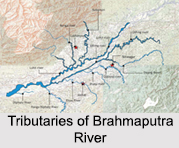

Tributaries of Brahmaputra River

Tributaries of Brahmaputra River are some of the major rivers of North-east India. They feed most of the fertile plains in the zone. The tributaries of Brahmaputra River are Lohit River, Dibang River, Subansiri River,Dhansiri River, Manas River, Torsa River, Dihing River, Teesta River, Sankosh River, Kopili River, Raidak River and Bhareli River. Several towns and cities have grown along the tributaries of Brahmaputra River.

Tributaries of Brahmaputra River are some of the major rivers of North-east India. They feed most of the fertile plains in the zone. The tributaries of Brahmaputra River are Lohit River, Dibang River, Subansiri River,Dhansiri River, Manas River, Torsa River, Dihing River, Teesta River, Sankosh River, Kopili River, Raidak River and Bhareli River. Several towns and cities have grown along the tributaries of Brahmaputra River.

Some of the major tributaries of River Brahmaputra are as follows:

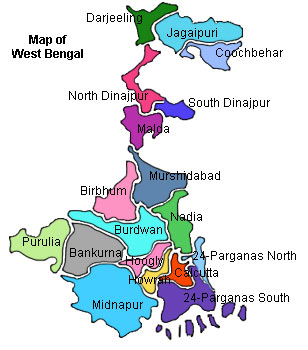

Teesta River, Tributary of Brahmaputra River

Teesta River rises in the eastern Himalayas, flows through the Indian states of West Bengal and Sikkim through Bangladesh and enters the Bay of Bengal. The river runs downhill through Sikkim and Darjeeling for 172kms, then meanders along the plains of West Bengal for about 98kms and eventually enters Bangladesh.

Raidak River, Tributary of Brahmaputra River

Raidak River, Tributary of Brahmaputra River

Raidak River is one of the main right bank tributaries of the Brahmaputra River in the lower course. The river is known as the Wong in its upper course in Bhutan and then the river traverses through the mountainous terrain in Bhutan and again comes back to the plains in India, in the districts of Jalpaiguri and other nearby localities.

Sankosh River, Tributary of Brahmaputra River

Sankosh River rises in northern Bhutan and then flows into the Brahmaputra in the state of Assam in India. In Bhutan, it is known as the Puna Tsang Chhu below the merging of several tributaries near the town of Wangdue Phodrang. The two largest tributaries of Sankosh River are the Mo Chhu and Pho Chhu.

Torsa River, Tributary of Brahmaputra River

Torsa River flows through the northern part of West Bengal. It flows past the important border towns of Phuntsholing (Bhutan) and Jaigaon and past the great tea estate of Dalsingpara and the Jaldapara Wildlife Sanctuary.

Bhareli River, Tributary of Brahmaputra River

Bhareli River is presently known as the Kameng River and flows in Arunachal Pradesh and Jia Bhoreli in Assam. The river originates in the eastern Himalayan Mountains, in Tawang district from the glacial lake below snow capped Gori Chen Mountain.

Dibang River, Tributary of Brahmaputra River

Dibang River flows through the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh. The river goes through its middle course across the Lower Dibang Valley District of Arunachal Pradesh. The Dibang River is an important tributary of the Brahmaputra. The Dibang River and Lohit River merge together and flow along the northern side of the Saikhowa Reserve forest.

Lohit River, Tributary of Brahmaputra River

Lohit River originates in eastern Tibet, in the Zayal Chu range and surges through Arunachal Pradesh for 200 kilometers, before emptying itself in the plains of Assam. Uncontrolled and turbulent is the features of the Lohit River. The Lohit River has derived its name because of its vigorous nature and thus it is also called the river of blood. The river flows through the Mishmi Hills, to meet the Siang at the head of the Brahmaputra valley.

Burhidihing River, Tributary of Brahmaputra River

Burhidihing River or Dihing River is one of the major tributaries of the Brahmaputra River in Upper Assam in north-eastern India. The River Burhidihing flowing at the speed of 103.58m at Khowang. This river is highly prone to floods and the previous highest flood level was measured to be 103.92m in1988.

Brahmaputra River Basin

The Brahmaputra River of South Asia is the fourth largest river in the world, in the aspect of annual discharge. The lower Brahmaputra River basin is prone to catastrophic flooding with major social, economic, and public health consequences. There is relatively little rainfall and snowfall information for the watershed, and the system is poorly understood hydrologically. Using a combination of available remotely sensed and gauge information, this study evaluates snow cover, rainfall and monsoon period discharge for a 14-yr time period during 1986-99.

The Brahmaputra River of South Asia is the fourth largest river in the world, in the aspect of annual discharge. The lower Brahmaputra River basin is prone to catastrophic flooding with major social, economic, and public health consequences. There is relatively little rainfall and snowfall information for the watershed, and the system is poorly understood hydrologically. Using a combination of available remotely sensed and gauge information, this study evaluates snow cover, rainfall and monsoon period discharge for a 14-yr time period during 1986-99.

The interannual rainfall variability is low and is a weak predictor of monsoon discharge volumes in the Brahmaputra basin. Strong evidence is found, however, that maximum spring snow cover in the upper Brahmaputra basin is a good forecaster of the monsoon flood volume. Despite the temporal and spatial limitations of the data, this study`s analysis demonstrates the potential for developing an empirical tool for predicting large flood events that may happen as an annual early window for justifying flood damages in the lower Brahmaputra basin, which is home to around 300 million people.

As the river Brahmaputra enters Arunachal Pradesh, it is called Siang and makes a very rapid flow from its original elevation in Tibet, and finally comes out in the plains, where it is called the Dihang River. This river flows for about 35 km and is joined by two other major rivers: Dibang and Lohit. From this point of convergence, the river becomes very wide and is called Brahmaputra. It is joined in Sonitpur District by the Jia Bhoreli and called the Kameng River where it flows from Arunachal Pradesh and then flows through the entire expanse of Assam. In Assam the river is at times as wide as 10 km.

Between Dibrugarh and Lakhimpur districts the river divides into two different channels---the northern Kherxhutia channel and the southern Brahmaputra channel. The two channels again join about 100 km downstream forming the Majuli island. At Guwahati near the ancient pilgrimage site of Hajo, the Brahmaputra flows through the rocks of the Shillong Plateau, and is at its narrowest at 1 km bank-to-bank. Because the Brahmaputra is the narrowest at this point the Battle of Saraighat was fought here. The first rail-cum-road bridge across the Brahmaputra was opened to public in April 1962 at Saraighat.

The old Sanskrit name for the river is Lauhitya, however the local name in Assam is Luit. The native inhabitants or the Bodos called the river Bhullam-buthur that means `making a gurgling sound`. This name was later Sanskritized into Brahmaputra.

The Brahmaputra is less polluted river in India, if compared to other rivers. The main problem related to this river is petroleum-refining units, which contribute most of the industrial pollution load into the basin and other medium and small industries. The main problem facing the river basin is that of regular flooding. Floods have been occurring more often in recent years with deforestation, and other human activities being the major causes.

The main rivers in the Brahmaputra basin are Brahmaputra River, Lohit River, Burhidihing River, Dihing River, Kameng River, Manas River, Sankosh, Yamuna, Teesta River, Rangeet River, Lachen River, Lachung River, Darla River and Jaldhaka River.