Gandhara sculpture has survived dating from the first to probably as late as the sixth or even the seventh century in a remarkably homogeneous style. Gandhara constituted the undulating plains, irrigated by the Kabul River from the Khyber Pass area, the contemporary boundary between Pakistan and Afganistan, down to the Indus River and southward towards the Murree hills and Taxila (ancient Taksasila), near Pakistan`s present capital, Islamabad.

Gandhara sculpture has survived dating from the first to probably as late as the sixth or even the seventh century in a remarkably homogeneous style. Gandhara constituted the undulating plains, irrigated by the Kabul River from the Khyber Pass area, the contemporary boundary between Pakistan and Afganistan, down to the Indus River and southward towards the Murree hills and Taxila (ancient Taksasila), near Pakistan`s present capital, Islamabad.

Gandhara became roughly a Holy Land of Buddhism and excluding a handful of Hindu images, sculpture took the form either of Buddhist sect objects, Buddha and Bodhisattvas, or of architectural embellishment for Buddhist monasteries.

Features of Gandhara Sculpture

Most of the arts were almost always in a blue-gray mica schist, though sometimes in a green phyllite or in stucco, or very rarely in terracotta. Gandhara sculpture primarily comprised Buddhist monastic establishments. These monasteries provided a never-ending gallery for sculptured reliefs of Lord Buddha and Bodhisattvas.

In the excavation among the varied miscellany of small bronze figures, though not often like Alexandrian imports, four or five Buddhist bronzes are very late in date. Mythical figures and animals such as atlantes, tritons, dragons, and sea serpents derive from the same source, although there is the occasional high-backed, stylized creature associated with the Central Asian animal style. Mouldings and cornices are decorated with acanthus, laurel, and vine, though sometimes with motifs of Indian, and occasionally ultimately western Asian, origin: stepped merlons, lion heads, vedikas, and lotus petals.

Double-Headed Eagle at Sirkap, in actuality a stupa pedestal, well demonstrates this enlightening eclecticism- the double-headed bird on top of the chaitya arch is an insignia of Scythian origin, which appears as a Byzantine motif and materialises much later in South India.

In Gandhara art the descriptive friezes were all but invariably Buddhist, and hence Indian in substance- one depicted a horse on wheels nearing a doorway, which might have represented the Trojan horse affair. The Dioscuri, Castor and Pollux, familiar from the previous Greek-based coinage of the region, appeared once or twice as standing figurines, presumably because as a pair, they tallied an Indian mithuna couple. There were also female statuettes, corresponding to city goddesses. Sculpture was, in the main, Hellenistic or Roman, and the art of Gandhara was indeed `the easternmost appearance of the art of the Roman Empire, especially in its late and provincial manifestations`. Naturalistic portrait heads, one of the high-points of Roman sculpture, were all but missing in Gandhara, in spite of the episodic separated head, probably that of a donor, with a discernible feeling of uniqueness. Some constitutions and poses matched those from western Asia and the Roman world; like the manner in which a figure in a recurrently instanced scene from the Dipankara jataka had prostrated himself before the future Buddha, is reverberated in the pose of the defeated before the defeater on a Trojanic frieze on the Arch of Constantine and in later illustrations of the admiration of the divinised emperor. One singular recurrently occurring muscular male figure, hand on sword, witnessed in three-quarters view from the backside, has been adopted from western classical sculpture. On occasions standing figures, even the Buddha, deceived the elusive stylistic actions of the Roman sculptor, seeking to express majestas. The drapery was fundamentally Western- the folds and volume of dangling garments were carved with realness and gusto- but it was mainly the persistent endeavours at illusionism, though frequently obscured by unrefined carving, which earmarked the Gandhara sculpture as based on a western classical visual impact.

The notable Begram hoard confirms articulately to the number and multiplicity of origin of the foreign artefacts imported into Gandhara. This further illustrates the foreign influence in the Gandhara art. Parallel hoards have been found in peninsular India, especially in Kolhapur in Maharashtra, but the imported wares are sternly from the Roman world. At Begram the ancient Kapisa, near Kabul, there are bronzes, possibly of Alexandrian manufacture, in close proximity with emblemata (plaster discs, certainly meant as moulds for local silversmiths), bearing reliefs in the purest classical vein, Chinese lacquers and Roman glass.

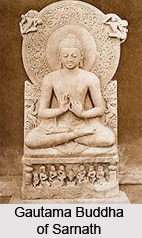

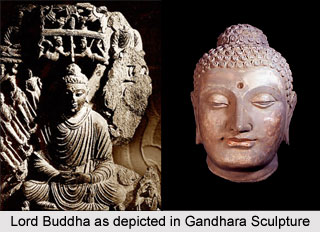

Lord Buddha in Gandhara sculpture

The distinguishing Gandhara sculpture is the standing or seated Buddha. This flawlessly reproduces the necessary nature of Gandhara art, in which a religious and an artistic constituent, drawn from widely varied cultures have been bonded. The iconography is purely Indian. The seated Buddha is mostly cross-legged in the established Indian manner. Buddha is clothed either in waves or in taut curls over his whole head. The extended ears are merely due to the downward thrust of the heavy ear-rings worn by a prince or magnate; the distortion of the ear-lobes is especially visible in Buddha, who, in Gandhara, never wore ear-rings or ornaments of any kind.

The distinguishing Gandhara sculpture is the standing or seated Buddha. This flawlessly reproduces the necessary nature of Gandhara art, in which a religious and an artistic constituent, drawn from widely varied cultures have been bonded. The iconography is purely Indian. The seated Buddha is mostly cross-legged in the established Indian manner. Buddha is clothed either in waves or in taut curls over his whole head. The extended ears are merely due to the downward thrust of the heavy ear-rings worn by a prince or magnate; the distortion of the ear-lobes is especially visible in Buddha, who, in Gandhara, never wore ear-rings or ornaments of any kind.

The western classical factor rests in the style, in the handling of the robe, and in the physiognomy of Buddha. The cloak, which covers all but the appendages (though the right shoulder is often bared), is dealt like in Greek and Roman sculptures; the heavy folds are given a plastic flair of their own, and only in poorer or later works do they deteriorate into indented lines, fairly a return to standard Indian practice. The `western` treatment has caused Buddha`s garment to be misidentified for a toga; but a toga is semicircular, while, Buddha wore a basic, rectangular piece of cloth. The head gradually swerves towards a hieratic stylisation, but at its best, it is naturalistic and almost positively based on the Greek Apollo, undoubtedly in Hellenistic or Roman copies.

Gandhara art also had developed at least two species of image in which Buddha is the fundamental figure of an event in his life, distinguished by accompanying figures and a detailed mise-en-scene. The small statuettes of the visitors emerge below, an elephant describing Indra. The more general among these detailed images, of which approximately 30 instances are known, is presumably related with the Great Miracle of Sravasti. In one such example, one of the adjoining Bodhisattvas is distinguished as Avalokiteshwara by the tiny seated Buddha in his headgear. Other features of these images include the unreal species of tree above Buddha, the spiky lotus upon which he sits, and the effortlessly identifiable figurines of Indra and Brahma on both sides.