Forests in ancient India have been well mentioned in Vedic texts, epics and Puranas. The principles regarding forests and their sustainable management are well encroached in pre-historic India. Like for instance, the Vedas provide description about the uses and management of forests. In ancient India, several plants were considered sacred because of their natural, aesthetic and medicinal qualities. Further, they were also believed to be significant because of their proximity to a particular god or goddess.

Description of Indian forest in Ramayana

It has been described in Ramayana that when Lord Rama is about to set out on his long exile in the forests south of the Gangetic plains, his mother, Kaushalya, expresses fear about his safety. Further, Lord Rama himself, in a bid to dissuade his wife, Sita, from following him into the woods, paints a similar portrait of the forest as a place of hidden menace. Even the word vana or forest was only given to lands where pleasure gave way to hardship. But a very different picture of the same lands emerges when Sita finally has her way and joins her husband in exile. The forested lands are considered as a source of pleasure for her. The twin themes of the forest as a place of dangers to be confronted and of beauty to be enjoyed run like a thread through subsequent sections of this great epic.

Description of Indian forest in Vedas

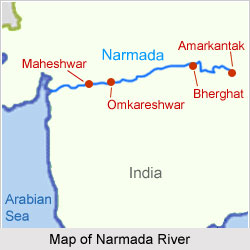

Vedic tradition confirms that every single village comes under three main categories namely Mahavan, Tapovan and Shrivan. By 3rd century AD, a fresh phase of town-building began in northern region of India. The scribes in the city had their own conceptions of what the forest was like. Most often, it was seen as another land, culture and space, set apart not only by its beasts and birds but also by its people. The forest was all that the city was not. The forest hermitage of Lord Rama and Lakshmana had the gleam of metal sword and axe to warn any intruder. In the texts from the Vedic times many centuries earlier Aryavarta, the land of the Aryans, was often co-terminus with the land of the black antelope. Sometimes defined in terms of geography, these were areas to the north of the Vindhya mountain chain. At other times, it included lands to the south. The societies beyond were seen as different in culture and lifestyle - unruly, barbaric and dangerous.

Description of Indian forest in Literature

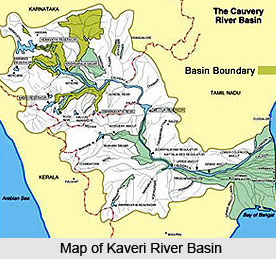

In the Tamil literature of the Sangam period dating back even further than Valmiki`s epic, land is divided into as many as five eco-types, ranging from the littoral to the wet rice fields. The ecology and nature of habitat changed over time. For instance, the dry land where people lived by herding became a land of great scarcity and danger when the rains failed, a place of menace where wolves and thieves attacked people. In a very different category were the medical treatises of Charaka and Susruta. In non-medical texts, composers see the animals or their habitat in a metaphorical and not a literal sense.

Archeological details of Ancient Indian forest

It is believed that archaeological evidence in the form of artefacts and animal remains are a more reliable guide to the changes in the land in centuries past than literature is. There is little doubt that there were several sites in India where hunting, the rearing of goats or sheep, and cereal-eating, often went together. The uncertain cycles of rainfall could push people relying on one occupation, towards another. There was no watertight division between hunter-gatherer, herder and cultivator. Long before the times referred to by the Sanskrit texts, wild animals were a major source of meats in the various sites of the Harappan civilisation. Over 1000 sites across north-western India and a range of bones of wildlife including the chital, hare, jackal, the great Indian one-horned rhino, wild ass and elephant have been found. These make up to a fifth of the animal remains in many sites in the Indus valley. In western Indian sites, most seeds found in the old dwellings are of wild plant species now extinct in the region.

Flora and Fauna of Ancient Indian Forest

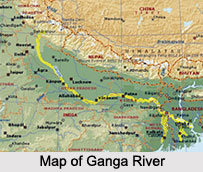

Some changes in faunal and floral distribution were probably the result of climatic shifts, such as increasing aridity in some tracts. Others may have been due to the impact of early humans. The swamp deer or barasingha was found in Mehrgarh in Baluchistan till around 300 BC. Its local extinction was probably a result of over-hunting and cultivation of its riverside habitat. Its vulnerability to such changes hastened its disappearance, though it survived along the Indus River till about a century ago. While people hunted a wide spectrum of wild animals, they herded only a few varieties. Such faunal collapses were still exceptional. One reason was the sheer immensity of the forest. Contrary to what was believed till recently, 2000 years before the Christian era did not see extensive denudation across much of the Indo Gangetic plain. Iron tools and fire are often celebrated in ancient Sanskrit texts as being responsible for replacing forests with farmland, and nature with culture. There is no doubt that cultivation, domestication, the taming of animals like the elephant and the rooster, the water buffalo and the zebu cow were major landmarks.

Rulers in ancient India claimed the woods, mountains and forests as their own. The forests were so immense that even a few centuries after the composition of Valmiki`s Ramayana in its final form, there were vast wooded areas even across the plains of north India. The Chinese traveller Hieun-Tsang in his travels across India during 7th century AD refers repeatedly to the immensity of the forested spaces that made travel unsafe and difficult. Thus, it can be said that epics and other narratives provide only a glimpse of what forests in ancient India were like.