Ezhavas or Tiyyas, originally the caste to whom the task of tapping toddy from palm trees was allotted, but later an agrarian tenant class, are considered to be the outcastes in the caste structure of Kerala. The Nayars, the Ezhavas, and the outcaste groups, led numerically by the Pulayas and the Paraiyas dominate Keralan Hinduism by the weight of their numbers. It is the Nayars and the Ezhavas, the largest, most enterprising, and in recent times the most communally aggressive of the Kerala castes, which have aroused most speculation regarding their origins.

Ezhavas or Tiyyas, originally the caste to whom the task of tapping toddy from palm trees was allotted, but later an agrarian tenant class, are considered to be the outcastes in the caste structure of Kerala. The Nayars, the Ezhavas, and the outcaste groups, led numerically by the Pulayas and the Paraiyas dominate Keralan Hinduism by the weight of their numbers. It is the Nayars and the Ezhavas, the largest, most enterprising, and in recent times the most communally aggressive of the Kerala castes, which have aroused most speculation regarding their origins.

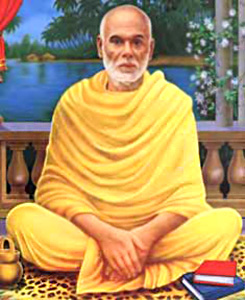

The Ezhavas, the most numerous of all the Hindu groups in Kerala, are also the most puzzling of its peoples. Subdued for centuries by the members of the Brahmins and the Nayar community, regarded as outside the fourfold structure of the caste system, they nevertheless retained a pride even in their position as the leading caste of the outcastes, and during the nineteenth century developed a great will to rise above the limitations which society had laid upon them, a will personified most dynamically in the teachings of Sri Narayana Guru, who was himself an Ezhava. Sri Narayana Guru was a social reformer and a Hindu saint of India.

The Ezhavas sought education, even established their own schools, and were encouraged by the British who admitted them into the civil service in Malabar at the same time as they were kept out of the service of the native princes and the Congress Party hierarchy; unfortunate Ezhavas took to business and the Congress Party hierarchy; unfortunate ones to radical rebellion, for the poor Ezhavas have long formed the dedicated core of the communist Party in Kerala. But whatever form the discontent of these people assumes, it shows an extraordinary spirit not in the least cowed by centuries of humiliation. Unwillingly, but inevitably, the higher castes granted the Ezhavas a place in the social sun, so that they have never, since independence, figured among the Scheduled Castes, which is the polite modern way of saying `the untouchables`. No group anywhere in India has so successfully, by its own efforts, removed from itself the double stigma of untouchability and ex-untouchability.

But the origin of the Ezhavas remains mysterious. There are legends which relate how they brought the coconut palm to Kerala. And the fact that the occupation of tapping the palm for toddy is traditionally reserved for Ezhavas emphasizes the connection between the people and the tree. Still it is only Ezhavas who walk lightly up the palm trunks, with square-bladed knives and earthenware pots hanging from their waists, to cut the flower buds and gather the liquor that in the eight hours will ferment into a heady and yeastry-flavoured beer.

Arjuna nritham or Mayilpeeli Thookkam or the dance of Arjuna is a ritual art which is practiced by the Ezhavas and is widely prevalent in the Bhagavathy temples of the southern parts of Kerala, primarily in Alappuzha, Kollam and the Kottayam District. Another is the Poorakkali, which is a folk dance, which is performed by the Ezhavas of Malabar, in the Bhagavathy temples in the form of a ritual offered in the month of Meenam which comes between the months of March to April in the Christian calendar. The most prominent deities of the Ezhavas are Muthappan, Kathivannur Veeran, Vayanattu Kulavan, Poomaruthan, etc.

Arjuna nritham or Mayilpeeli Thookkam or the dance of Arjuna is a ritual art which is practiced by the Ezhavas and is widely prevalent in the Bhagavathy temples of the southern parts of Kerala, primarily in Alappuzha, Kollam and the Kottayam District. Another is the Poorakkali, which is a folk dance, which is performed by the Ezhavas of Malabar, in the Bhagavathy temples in the form of a ritual offered in the month of Meenam which comes between the months of March to April in the Christian calendar. The most prominent deities of the Ezhavas are Muthappan, Kathivannur Veeran, Vayanattu Kulavan, Poomaruthan, etc.

Ezhava legends suggest that they first came as warriors; no other evidence confirms this, and in historical times their role has been completely unmilitary. Yet there may be some ironic truth in the tradition, for the Tamil poems of the second and the third century tell of Ceylonese - as many as ten thousand at a time - having been brought to India as prisoners of the Dravidian kings round about the beginning of the Christian era and having been used as coolies; the subordinate position of the Ezhavas in the caste structure might well be explained by the fact of their being the descendants of liberated prisoners.