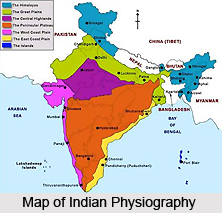

One look at the contour map of Asia will instantly drive home the distinguishable individuality of the Indian subcontinent from the remaining continent of Asia. It is the rawest geographical unit, which has evolved into a very unique civilisation. The majority of it has been additionally accustomed by a common foreign rule, spanning over two centuries. The countries that build the Indian subcontinent today are- Pakistan in the northwest, India in the centre, Nepal in the north, Bhutan in the north-east and Bangladesh in the east. India shares its land boundaries with all of them. But, the interesting part lies in the fact that none of them have a common border with one another. While India, Pakistan and Bangladesh are democracies, Nepal and Bhutan are kingdoms. The island states of Sri Lanka, and the Maldives are India`s southern neighbours in the Indian Ocean.

One look at the contour map of Asia will instantly drive home the distinguishable individuality of the Indian subcontinent from the remaining continent of Asia. It is the rawest geographical unit, which has evolved into a very unique civilisation. The majority of it has been additionally accustomed by a common foreign rule, spanning over two centuries. The countries that build the Indian subcontinent today are- Pakistan in the northwest, India in the centre, Nepal in the north, Bhutan in the north-east and Bangladesh in the east. India shares its land boundaries with all of them. But, the interesting part lies in the fact that none of them have a common border with one another. While India, Pakistan and Bangladesh are democracies, Nepal and Bhutan are kingdoms. The island states of Sri Lanka, and the Maldives are India`s southern neighbours in the Indian Ocean.

The current relief features have developed as a consequence of alterations, which have occurred over millions of years. The remains of vegetative and animal life conserved in various layers of rocks, facilitate to fix their age. Geologists have assembled the story of the Indian subcontinent together, penned as if it were in the rocks.

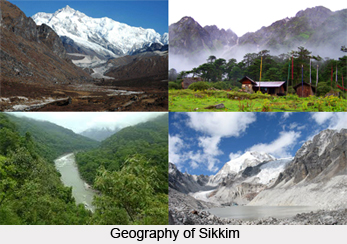

The story takes one millions and millions of years back into the geological yesteryear. The world during that time was hugely unlike from what it is now. The area that now comprises the Himalayas and the Northern Plains of India was under a sea, called `Tethys`. It was a lengthened and shallow sea, infixed between the two massive land `masses - `the Angaraland` in the north and `the Gondwanaland` in the south. The Tethys extended from the present Indo-Myanmar border in the east and cut across a wide area consisting of western Asia, northeastern and central parts of Africa, before it united with the South Atlantic Ocean in the Gulf of Guinea in the west. For millions of years uncovering of the two landmasses led to deposition of silt in the Tethys. These two colossal landmasses were gradually but progressively leading towards each other. This lateral compression force, moving from two opposite directions made the sea not only shrivel further, but also heave up establishing a string of islands to begin with and over millions of years into the grand fold mountains- the Himalayas of today.

As the Himalayas began to increase in altitude, the rivers and other factors of denudation became more and more vigourous in corroding them, and transporting enormous amount of silt to deposit in the ever-contracting Tethys.

The outcome has been what is called the Northern Plains or the Indo-Gangetic plains, lying in India and Pakistan. The river Brahmaputra too followed the similar line in the northeastern part of India and Bangladesh. If one looks at the map of the Ganga-Brahmaputra delta cautiously, one will get the trace to reason out that the process is still on and the land is tardily but certainly gaining, pushing the sea back.