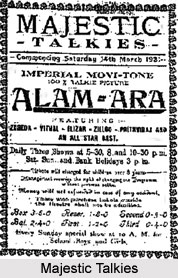

Era of talkies in India led to the introduction of sound; films incorporating synchronized dialogue were acquainted and were known as "talking pictures," or "talkies." The film viewers were bestowed with a surprising gift, the silent era had ended, and films now had sound, so we could hear actors and actresses talking. In 1931 came the first Indian talkie: Alam Ara. It was a costume drama full of fantasy and with many melodious songs to intensify the audience`s emotions and it was a stunning success. It was produced by Imperial Movie tone, Bombay. The film was released on 14th March 1931 at Majestic Cinema, Girgaon, Bombay. The film starred Prithviraj Kapoor (father of late Raj Kapoor), Zubeida, Master Vithal, Zillo and Wazir Mohammad Khan. The film had 7 songs and the music director was Firozeshah M. Mistri. The curiosity was irresistible. Crowds thronged to watch Alam Ara, India`s first talking movie. The film had an interesting ensemble. The hard work paid off. Alam Ara not only became a runaway success, it also became the template of future.

Era of talkies in India led to the introduction of sound; films incorporating synchronized dialogue were acquainted and were known as "talking pictures," or "talkies." The film viewers were bestowed with a surprising gift, the silent era had ended, and films now had sound, so we could hear actors and actresses talking. In 1931 came the first Indian talkie: Alam Ara. It was a costume drama full of fantasy and with many melodious songs to intensify the audience`s emotions and it was a stunning success. It was produced by Imperial Movie tone, Bombay. The film was released on 14th March 1931 at Majestic Cinema, Girgaon, Bombay. The film starred Prithviraj Kapoor (father of late Raj Kapoor), Zubeida, Master Vithal, Zillo and Wazir Mohammad Khan. The film had 7 songs and the music director was Firozeshah M. Mistri. The curiosity was irresistible. Crowds thronged to watch Alam Ara, India`s first talking movie. The film had an interesting ensemble. The hard work paid off. Alam Ara not only became a runaway success, it also became the template of future.

The second talkie film released in India was Shirin Farhaad, on 30th May 1931. It was produced by Madan Theatres, Kolkata and directed by its owner Mr. J.J. Madan. It had 18 songs. Indra Sabha which was released in 1932 had as much as 69 songs in it! It was produced by Madan Theatre, Calcutta and directed by J.J. Madan. The film starred Master Nissar, Jahan Aara, Kazzam, Miss Silvasia and others. The first ever color film made in India was Kissan Kanhaiya produced by Imperial Film Co. This film was released in 1973. Moti B. Gidwani directed it, and its music was composed by Ram Gopal Pandey. The film had 10 songs, which were released by Gramophone Records.

In that year, 27 films were made in four languages - Hindi language, Bengali language, Tamil language and Telugu language. The introduction of sound generated ever-increasing emphasis on music and song. The phenomenal success of Alam Ara inspired many other directors to follow in its footsteps. Music and fantasy came to be seen as vital elements of the filmy experience. At times, the emphasis on music was overdone. However it is significant that music came to be regarded as a defining element in Indian cinema.

With the spreading popularity of this new medium of mass entertainment, film directors became more audacious and explored new areas. The 1930s saw the emergence of a fascination with social themes that affected day to day living. V. Shantaram, for example, in his film Amritmantha (1934), held up for scrutiny the theological absolutisms and ritualistic excesses that were gathering momentum at the time, while the landmark Devdas (1935) sought to explore the self-defeating nature of social conventionalist. The character of Devdas has been reincarnated many times in Indian cinema. Jeevana Nataka (1942), another significant film of this period, had as its theme the injurious effects of modernization - a love triangle in which Mohan, driven to alcoholism by his infatuation with the main actress, drives his wife to suicide.

With the spreading popularity of this new medium of mass entertainment, film directors became more audacious and explored new areas. The 1930s saw the emergence of a fascination with social themes that affected day to day living. V. Shantaram, for example, in his film Amritmantha (1934), held up for scrutiny the theological absolutisms and ritualistic excesses that were gathering momentum at the time, while the landmark Devdas (1935) sought to explore the self-defeating nature of social conventionalist. The character of Devdas has been reincarnated many times in Indian cinema. Jeevana Nataka (1942), another significant film of this period, had as its theme the injurious effects of modernization - a love triangle in which Mohan, driven to alcoholism by his infatuation with the main actress, drives his wife to suicide.

The interplay between tradition and modernity in its various guises began to interest Indian filmmakers more and more, as evident in films like Maya (1936) and Manzil (1936).Western influences, however, still loomed large in at least one dimension of the Indian popular cinema in the late 1930s. India`s most exciting daredevil from the 1930s to the 1950s was Nadia, daughter of a British father and Greek mother. Billed as fearless, Nadia, her story has recently been told by her grand nephew, Rijad Vinci Wadia (1993) in Fearless: The Hunterwali Story, a 75-minute film documentary.

By the 1940s, however, a winning formula for success at the box office had been forged, consisting of song, dance, spectacle, rhetoric and fantasy. A close and significant relationship between the epic consciousness and the art of cinema had been established. Moreover, film was increasingly being recognized as a vital instrument of social criticism. It was against this background that film directors like V. Shantaram, Raj Kapoor, Mehboob Khan, Bimal Roy had chosen to make their films, films that were to generate not only national but also international interest.

The foundations of the Indian popular cinema as both entertainment and industry were laid in the 1940s. Raj Kapoor became a celebrity not only in India but also in other parts of South Asia, Southeast Asia, East Africa, the Middle East and the Soviet Union. Gifted film directors such as Bimal Roy, Guru Dutt and Raj Kapoor won increasing recognition for Indian popular cinema in many parts of the world. Film historians regard the 1950s as the Golden Age of Indian popular cinema. By now cinema was firmly established as art, entertainment and industry.

The foundations of the Indian popular cinema as both entertainment and industry were laid in the 1940s. Raj Kapoor became a celebrity not only in India but also in other parts of South Asia, Southeast Asia, East Africa, the Middle East and the Soviet Union. Gifted film directors such as Bimal Roy, Guru Dutt and Raj Kapoor won increasing recognition for Indian popular cinema in many parts of the world. Film historians regard the 1950s as the Golden Age of Indian popular cinema. By now cinema was firmly established as art, entertainment and industry.

While the popular tradition of Indian filmmaking was developing with undiminished vigour, by the mid 1950s, a distinctly `artistic` cinema took shape, thanks to the pioneering efforts of the Bengali filmmaker Satyajit Ray. His Pather Panchali (Song of the Road) of 1955 won for Indian cinema great international recognition and critical acclaim. It was given the `best human document` award at the 1956 Cannes film festival and went on to win awards at film festivals in San Francisco, Vancouver, Ontario and elsewhere. Pather Panchali, based on a well-known Bengali novel, realistically and sensitively chronicles the privations and hardships encountered by a Brahmin family at the beginning of the present century. If Indian popular filmmakers looked towards Hollywood musicals for inspiration, Satyajit Ray`s cinematic imagination was stirred by the work of French director Renoir and the Italian neo-realists.

Pather Panchali along with Aparajito (The Unvanquished, 1956) and Apur Sansar (The World of Apu, 1959) - generally referred to as the Apu Trilogy - are regarded as masterpieces of world cinema. After making the trilogy, Satyajit Ray went on to create such outstanding works of cinema as Charulata (The Lonely Wife, 1964), Devi (Goddess, 1960) and Jalsaghar (Music Room, 1958). Ray`s cinema with its emphasis on realism, psychological probing, visual poetry, outdoor rather than studio shooting, and the use of non-professional actors was in sharp contrast to the practices of Indian popular cinema. Before his death, Ray was awarded the Lifetime Award by Hollywood and was the only Indian director to be singularly honoured by President Mitterand of France, who flew to Kolkata to bestow on him the Legion of Honour. Satyajit Ray was largely responsible for the creation of an internationally recognized artistic cinema in India.

Very quickly, a number of highly talented directors, including Mrinal Sen, Adoor Gopalakrishnan, G. Aravindan, Mani Kaul, Kumar Shahani, Buddhadeb Dasgupta, Gautam Ghose, Ketan Mehta, Aparna Sen, Govind Nihalani, Shyam Benegal, Vijaya Mehta, Shaji Karon emerged as able expositors of artistic cinema. Their body of work is normally referred to as New Cinema, as characterised by the qualities established by Ray. Another filmmaker and contemporary of Ray, Ritwik Ghatak, have belatedly won national and international recognition for his audacious exploration of political themes, using the strengths of Art Cinema and Commercial Cinema.

Very quickly, a number of highly talented directors, including Mrinal Sen, Adoor Gopalakrishnan, G. Aravindan, Mani Kaul, Kumar Shahani, Buddhadeb Dasgupta, Gautam Ghose, Ketan Mehta, Aparna Sen, Govind Nihalani, Shyam Benegal, Vijaya Mehta, Shaji Karon emerged as able expositors of artistic cinema. Their body of work is normally referred to as New Cinema, as characterised by the qualities established by Ray. Another filmmaker and contemporary of Ray, Ritwik Ghatak, have belatedly won national and international recognition for his audacious exploration of political themes, using the strengths of Art Cinema and Commercial Cinema.