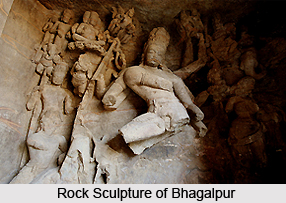

Rock-cut architecture occupies a significant place in the history of Indian architecture. This is different from `building up` in many essential ways. Firstly, art is more similar to sculpture than architecture, because, a solid body of material (rock) is taken and is then carved into a final product. Secondly, the craftsman is not excessively alarmed with bridges, forces, columns, and all the other architectural characteristics- these can be carved, but rarely plays a structural role. Indian rock-cut architecture is predominately religious in nature. Caves, that were expanded or wholly artificial, are the most sacred, small and dark surviving examples of rock-cut beauty. The original cave specimens are found in western Deccan, largely Buddhist shrines and monasteries, dating between 100 B.C. and 170 A.D. Some of the most erstwhile cave temples include Bhaja Caves, Karla Caves, Bedse Caves, Kanheri caves and parts of the Ajanta Caves. Although freestanding structural temples were built during the 5th century, rock-cut cave architecture turned classier, like the Ellora Caves, terminating in the monolithic Kailash Temple.

The earliest expanded edifices in India are in several cases not shrines, but secular buildings. Palaces and architecturally intricate city gates are portrayed in the early reliefs, predominantly at Saiki and Amaravati and on the frontages of rock-cut monuments, their descriptions flourishing in literature. Exceptions include the Bharhut relief of the Bodhi-tree shrine in Bodh Gaya and others from numerous early sites, demonstrating structures of a distinctly religious nature. Likewise the Graeco-Roman tradition, consecrated buildings were modified from secular ones. Widespread excavations of huge sites occupied over long periods, however, have so far generated peculiarly few central worldly remains- like Kumrahar (Patna), in the old Mauryan capital of Pataliputra, a pillared hall at Sisupalgarh outside Bhubaneshwar, a set of columns from a pillared hall of doubtful date, a palace dating back to the 1st/2nd centuries A.D. at Kausambi. Colossal early ramparts have been discovered in number of sites, particularly in Rajgir, capital of Magadha during the time of Buddha, and more recent ones at Kausambi. Though wood was the primary construction substance, there is sufficient proof of the employment of brick and sometimes occasionally (primarily in the foundation stone), and it is amazing that so trivial have so far been discovered by the digger`s shovel. Indisputably, the first shrines of any architectural pretence were patterned on the designs and constructions of secular buildings, beginning with the ordinary house.

To start with, and in their simplest form, the shrines of the subcontinent seem to have been hypaethral (open air), ranging from the mere enclosure by a vedika of a linga (sacred phallus) or a blessed tree, to pillared arcades, like the Bodhighara portrayed on the Bharhut relief. The earliest inscriptional verification of a stone shrine, the pujiifila priikiira (`worship stone enclosure`) of the Ghosundi inscription, indicates that it was open-air, presumably with rectilinear sides and girded not by a stone vedika, established on a wooden fence, but by vertical slabs of thin stone between posts. When an existing ground sketch is circular, like at Besnagar, or apsidal-ended, a roofed construction is generally connoted. The single apsidal-ended construction, with its hastiha (elephant-back) roof, is widely known from a relief, from its accurate replica in the rock-cut chaitya hall and from subsisting structures of later date. Buildings, not always religious, with pointed tiled roofs appear on one or two reliefs, and small roofed huts are habitually demonstrated. The coronating dome-like constituent, later to be known as the South Indian fikhara, appears on several little tower-like shrines and in a developed octagonal shape, on a relief from Ghalkasala. Gandhara alone, besides incalculable relief illustrations of architectural essentials and even small shrines, provide instances of total standing edifices, tiny and uncomplicated though they are. Where their superstructures are concerned, they are habitually of the throated dome-like category of circular form. Very similar to the Gandhara relics, they may not be prior to 4th or 5th century A.D.

Simple dolmenoid shrines were undoubtedly manufactured from monolithic slabs from quite premature times, as they still are in present times, and this method has irregularly been used for more developed buildings. The structure and representation of the altars used in Vedic rites had an extensive influence on later temples, but the erstwhile shrines seem to have originated independently. It is therefore towards memorials, shrines and monasteries, delved cave-like into the upright faces of low cliffs and beautified with such architectural features as farads, interior columns and even beams, hewn out of the solid stone, that one must look for the first outlasting examples of Indian architecture, until well into the present era. That these monuments certainly had replicated all the characteristics of modern free-standing buildings in wood admits them to be considered as architecture and used as architectural records, bizarre as the form may at first emerge. It had happened in the Middle East and Ethiopia also. Its introduction in India under Mauryan benefaction indeed indicates a linkage, as with so many facets of early Indian art, with western Asia. Rock-cut monuments simultaneously were especially well adjusted to Indian conditions- material and divine. Cool in summer, warm in winter, cave-temples and monasteries were well adjusted to the Indian clime. Low cliffs often intended water falls, a stream through a valley, or simply water penetrating down from the tableland above. More than this, the conception of the cave with its elementary, uncreated (svayambhu) nature impresses upon the rudimentary chords on Indian spiritualism. Simultaneously, it should not be neglected that for every rock-cut monument there must have been loads, if not hundreds of structural buildings of which no traces survive.

From the late 2nd century H.C., till mid-2nd century A.D., when such constructions stopped pretty suddenly, a thousand caves of changing sizes and degrees of expansion were excavated in northern Konkan (coastal region, south of present day Mumbai), in the western ghats behind the seaward region, and in the Sahyadri hills, as midland as Aurangabad, the ancient Aparanta. They were seemingly all for Buddhist communities. This first great explosion of activity, the Hinayana phase, was unmatchable elsewhere in the world, until the Mahayanas started out approximately three centuries later, appears to have been nurtured by dynamic trade with the rest of India, originating in the Konkan coast. The caravan paths were pushed to climb the Western Ghats before continuing towards the north and east, an energetic merchant community, and an emphatic dynasty, the Satavahanas, with their capital in Mathura. Whatever the scenes portray, there is no refusing the extremely secular atmosphere, which places them besides the conventional Indian sculpture. Interestingly though, they are all part of stone bowls, whose purpose is not comprehensible, though one at least was established in a Buddhist sangharama.

A number of statuettes represented Kusana kings and princes, customarily in their resident costume- the trousers or boots, the tailored tunic and the sharpened `Scythian` cap of Central Asian horsemen- as they appear in their coins. Likewise the Gandhara, reliefs quite often portrayed figures in `Scythian` garb, seemingly members of the foreign reigning, who had held back their characteristic dress even while changing into Buddhism and Jainism and while worshipping at liiga shrines. What makes the greater free-standing sculptures surpassing is the fact that they are portraits, which are priceless in Indian art and that the most significant of them were found, like correspondingly dressed someone from Surkh Kotal in Afghanistan, in what appears to have been a royal shrine in the close by village of Mat. One of these grand figures, sadly headless, seated in European style, on a chair-like lion throne of apparently non-Indian origin, may embody Wema Kadphises, a precursor of Kanishka. There is no doubt, however, about the destiny of the legendary standing figure, also headless, known throughout an inscription to be the outstanding Kanishka, one of the premium works of art ever formed on Indian soil. In fashion it blends Indian motifs with a hard and notched angularity, recalling the Kusanas of Central Asian origin. In this manner it is exclusive as the only chief Indian work of art to portray an unfamiliar stylistic influence that has not arrived from Iran or the Hellenistic or Roman world.

A number of crouching figurines in the same costume, encompassing a very bulky one in worship as Mahadeo in a contemporary Mathura temple, are not essentially Kusana rulers, because Surya, the sun god and his two attendees are depicted in a diversified northern dress of which traces, predominantly the boots, continue to differentiate figures of Surya for centuries.