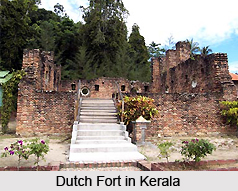

Dutch rule in Kerala was more centered around the spice trade rather than the expansion of the territory. The Dutch first captured Cochin in the year 1661 and they finally expelled the Portuguese in 1663, and from that time the Cochin Jews, who were oppressed by the Portuguese, lived in peace. In the year 1594, a meeting of merchants in Amsterdam founded the Dutch East India Company, and in 1604 a Dutch fleet under Steven Van Der Hagen appeared off Calicut and concluded a treaty with the Zamorin aimed at driving the Portuguese out of India. Like the Cochin Jews, the Syrian Christians welcomed the displacement of the Portuguese by the Dutch in the year 1663. The persecution which in one form or the other they had endured since the banning of the Persian bishops in the year 1558 was ended, and in 1665 their episcopal succession was re-established by the coming of a bishop upholding the Syrian liturgy who came unimpeded by the Dutch.

Dutch rule in Kerala was more centered around the spice trade rather than the expansion of the territory. The Dutch first captured Cochin in the year 1661 and they finally expelled the Portuguese in 1663, and from that time the Cochin Jews, who were oppressed by the Portuguese, lived in peace. In the year 1594, a meeting of merchants in Amsterdam founded the Dutch East India Company, and in 1604 a Dutch fleet under Steven Van Der Hagen appeared off Calicut and concluded a treaty with the Zamorin aimed at driving the Portuguese out of India. Like the Cochin Jews, the Syrian Christians welcomed the displacement of the Portuguese by the Dutch in the year 1663. The persecution which in one form or the other they had endured since the banning of the Persian bishops in the year 1558 was ended, and in 1665 their episcopal succession was re-established by the coming of a bishop upholding the Syrian liturgy who came unimpeded by the Dutch.

In the year 1555, however, the Portuguese at Mattancherri constructed as a gift to the Raja of Cochin a large stone palace with thick walls and a heavy tiled roof, which still survives under the misleading name of the Dutch Palace and which possesses one of the finest groups of traditional Indian murals paintings in Kerala. The Dutch Palace set a fashion for mansions made of masonry, and at the time of the Portuguese rule, many such buildings were apparently constructed for the use of the Nayar nobles in trading towns like Cochin, Quilon and Kolikod (Calicut).

Conquest of Dutch in Kerala

The aim of the Dutch at the commencement of the 17th century was to take over the whole of the Portuguese trading empire in Asia. But though they made their first contacts with the Keralite princes early in the 17th century, and continued friendly relations with them for half a century, it was not until 1658, when they threw out the Portuguese from Ceylon, that they finally began a serious campaign on the Malabar Coast. During the end of the same year, they made the first attack in strength, when Admiral Van Goens captured the Portuguese fort at Quilon. Next spring their garrison there was forced to retreat to Colombo, but soon a succession dispute in Cochin gave an excuse to intervene on a larger scale and with at least a show of legitimacy. In the year 1646, the senior line of the royal house of Cochin had proved insufficiently docile for the Portuguese, and had been dispossessed. Their cause was openly supported by the Zamorins of Calicut and some of the major princes of central Kerala. Secretly the Paliath Achan, the Lord of Paliyam and hereditary Chief Minister of Cochin State, was also in their favour; his support was vital since he owned the strategic Vypeen Island which defended the entrance of Cochin harbour.

Advised by the Paliath Achan, the head of the dispossessed Cochin line, Vira Kerala Varma, paid a visit to Colombo and laid his case before the Dutch, who agreed to help him, and in early 1661 an expedition under Van Der Meyden landed near Cranganore, concluded an agreement with the Zamorin, and captured the Portuguese fort of Pallipuram. At this time they did not feel enough powerful to make a direct assault on Cochin, but in the month of January 1662, they returned and fought a battle outside the palace of Mattancherri in which the Raja was killed and the captured Rani was forced to recognize their protege as the lawful king of Cochin. But the capture of the Portuguese fort which followed this partial victory dragged on for two months and so wiped out the Dutch forces that they withdrew, returning again after the monsoons with a much larger force which cut of Portuguese supplies by occupying the island of Vypeen and conquering the native town of Ernakulam.

On the seventh of January, the Fort Cochin fell to the assault of the Dutch and their Malayan allies, and, dressed in mourning; the successors of Vasco da Gama and Albuquerque handed over the keys of the city and took their dignified departure. The Portuguese epoch in Kerala was at an end. The Dutch were to remain in the state until they were finally expelled by the British in the year 1796. But one can hardly talk of a Dutch era in the same way as one discusses about a Portuguese or a British era.

The Dutch came merely for trade. They had no desire either to win a land for their God or to become the political overlords of the Malabar Coast. Their policies were thus less forceful and less impetuous as compared to the Portuguese. In order to safeguard their base at Cochin they had to treat this one principality as a vassal state and to hold fortresses on its borders, and for the same reason they got involved in the wars between principalities which disturbed Kerala during the 18th century.

The port of Cochin, which had degraded in the last generations of Portuguese rule, revived under the Dutch. The Dutch governance was relatively efficient, and, for the period, surprisingly unmarred by corruption. There were no major barbarities when wars were waged against local chieftains. The Dutch attitude towards the people of Kerala was one of liberal tolerance; Jews, Syrian Christians, Muslims, Hindus, all were free from any kind of persecution, and even the Latin Catholics, after suffering a few disabilities in the very early years of Dutch rule, were afterwards provided so much liberty that the Pope Clement XIV in the year 1772, sent a message to the Governor of Cochin giving thanks to him for his Christian acts of kindness.

Contribution of Dutch rule in Kerala:

The Dutch, unlike the Portuguese before or the British after them, were not interested in bringing the benefits of Western civilization to the Keralas, except by way of trade. They established no colleges, founded no libraries, and made almost negligible attempt at missionary activities. Even if they employed the Ezhavas as soldiers and at times in other humble capacities, and thus gave assistance to this caste indirectly in its long climb out of untouchability, they were moved by no passion to assert the equality of the humble before God like that which sent Francis Xavier to preach among the poor and lowly class of fishermen.

The attitude of the Dutch towards the places where they settled was particularly significant. While the Portuguese had constructed in Cochin as if they were constructing a future metropolis, with a massive fort, convents, churches, colleges and palaces, the Dutch purposely reduced the fort area and the city, and pulled down probably all the public buildings which the Portuguese had erected. The buildings constructed by them were devoted to commerce, and if the Portuguese are reminded by the great churches they left behind in the villages of the Malabar Coast, the Dutch are reminded by the warehouses at Mattancherri along the waterfront and the merchants` houses in Fort Cochin. The one area in which they benefited Kerala was in the extension of the agricultural improvements which was introduced by the Portuguese and in the introduction of such industries as salt-making and dyeing.

The attitude of the Dutch towards the places where they settled was particularly significant. While the Portuguese had constructed in Cochin as if they were constructing a future metropolis, with a massive fort, convents, churches, colleges and palaces, the Dutch purposely reduced the fort area and the city, and pulled down probably all the public buildings which the Portuguese had erected. The buildings constructed by them were devoted to commerce, and if the Portuguese are reminded by the great churches they left behind in the villages of the Malabar Coast, the Dutch are reminded by the warehouses at Mattancherri along the waterfront and the merchants` houses in Fort Cochin. The one area in which they benefited Kerala was in the extension of the agricultural improvements which was introduced by the Portuguese and in the introduction of such industries as salt-making and dyeing.

Politically the Dutch age in the state of Kerala does not stand out like the Portuguese, primarily because the issues had ceased to be clearly defined, and their exponents had ceased to be passionately involved. The Dutch never sought the control of the Malabar Coast, never thought in terms of demolishing the Arabs or of cutting down the Zamorin to a puppet like the Raja of Cochin. At most, in the beginning, they had some idea of keeping a balance of power among the fifty separate principalities into which Kerala was divided in the year 1663 when they reached Cochin, and of drawing the advantage not politically but commercially by commanding the pepper trade and governing the prices to their own advantage.