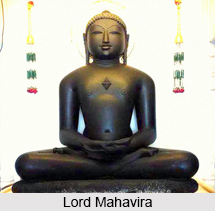

During the medieval period the Digambara Sect or ascetic community had split into different sects. The Mula Sangha, i.e. the `Root Assembly,` had descended from Lord Mahavira through Kundakunda. Later it was split into four sections called Sena, Deva, Simha, and Nandin. Apart from these there were also rival Digambara sects such as the Dravida Sangha at Madurai which allowed bathing.

The prominent figure during the medieval Digambara Jainism was the bhattaraka, meaning `learned man.` They were the head of a group of monks in a matha or monastery. These bhattaraka wore orange coloured robes except when eating or initiating another bhattaraka. There were thirty-six bhattaraka thrones around India and few of these bhattarakas became Emperor-like figures. These bhattaraka helped in perpetuating Digambara Jainism. In the fifteenth century a Rajasthan based bhattaraka consecrated thousand Jin-images to send them all over India in order to replace those demolished by the Muslims.

Jainism in South India went into retreat during the Hindu Renaissance period. In the eighth century there was a terrible persecution of Jains. The Hindu temples in Tamil Nadu have depicted the impaling of eight thousand Jains at Madurai. The Virashaiva movement had also killed Jains in Karnataka. These incidents took place in the twelfth century. However, the Jain followers had prominent positions in the Vijayanagar Empire that was established in 1336. Nevertheless, the number of Jain followers began to decline with many Jains converting to Hinduism. Maximum number of Jain followers was mainly centred in South West India. Jainism still kept on spreading and was exemplified by the erection of great images of Bahubali at Karkala in 1432 and at Venur in 1604.

Again during the late sixteenth century another important reform movement began within Digambara Jainism in Agra. The movement was forged in the first half of the seventeenth century by Banarsidass and the Adhyatma movement and his later devotees such as Pandita Todarmal of Jaipur. The movement had a profound effect on the Digambara society. The movement provided a new thought and direction to the sect by largely eliminating the crippling excesses of ritualism. It also helped in the process of awakening the community to a deeper meaning of its faith.

By the nineteenth century the thrones of bhattaraka in India had almost become had lost its significance except the oldest ones at Mudbridri and Sravana Belgola. These are still well-known and celebrated. There are also two in Kolhapur. Presently the Digambara Sect and Swetambar Sect flourish independently of each other.