With the inauguration of British Empire in India, the educational system was given a changed style, with emphasis given on every single detail. In all, everything took a Westernised appearance. Developments in Botany also gained much impetuous. Scientific experiments which had already been started by talented natives, the educated middle-class, gained a specific contour with the active participation of the gifted British. This indeed created a history. It was precisely under English administration that developments in Botany adopted a serious turn, with surveyors and other knowledgeable men arriving in India to have a slice of Indian flora.

With the inauguration of British Empire in India, the educational system was given a changed style, with emphasis given on every single detail. In all, everything took a Westernised appearance. Developments in Botany also gained much impetuous. Scientific experiments which had already been started by talented natives, the educated middle-class, gained a specific contour with the active participation of the gifted British. This indeed created a history. It was precisely under English administration that developments in Botany adopted a serious turn, with surveyors and other knowledgeable men arriving in India to have a slice of Indian flora.

In 1778, Johan Gerhard Koenlg (1728-1785) was engaged as the Natural Historian of the British East India Company in Madras. He introduced the Linnean binomial system of nomenclature in India. He also led a loosely grouped number of naturalists in Madras in an organisation called "The United Brethren".

Within the period of 1785-89, Patrick Russell (1725-1805) was named Naturalist in Madras, succeeding Koenlg. He collected in the period within 1785-87 approximately 900 plants in the Circars.

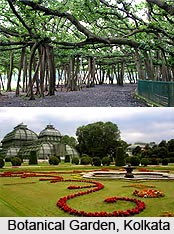

In 1787, Colonel Robert Kyd (1746-1793) gained the support of the East India Company for the initial establishment of the Calcutta Botanical Gardens at Sibpur, near Calcutta. This can be called a momentous step towards a historical development in Botany and its associates for future years. By 1790, Kyd had established an inventory of over 4000 plants at the garden, with an emphasis on the collection and growth of teak trees.

In 1785, Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820), President of the Royal Society of London, began his service as a consultant to the Company on botanical matters. For several decades he maintained influential ties with Sir William Jones (1746-1794), Colonel Robert Kyd (1746-1793), William Roxburgh (1751-1815), Francis Buchanan (1762-1829), Nathaniel Wallich (1786-1854), and other early botanists in India. He received from them many collections of dried plants for placement in the herbarium of the Royal Botanic Garden at Kew, England.

In 1793, Benjamin Heyne joined the Company`s service and was assigned in 1796 as the Madras Botanist to Samalkot. Then in 1800, he was placed in charge of the botanical garden at Bangalore. Here, Heyne made a considerable collection of plant specimens which were forwarded to London.

Within the years of 1793-1813, William Roxburgh (1751-1815) received employment as Superintendent of the Calcutta Botanical Gardens. He laid out the foundation of taxonomic research through his collection and description of living plants at the Botanical Garden. Derived from Roxburgh`s studies were his Plants of the Coast of Coromandel (1795-1820), Hortus Bengalensis (1814) and Flora Indica (1820-24). Such promising and well-researched works of gifted Englishmen, further heightened the sophisticated developments in Botany in India, a country which is primarily rich in plants.

In the time period of 1794-1803, Francis Buchanan (1762-1838) conducted several famous plant collecting tours and surveys, comprising places like Ava, Pegu and the Andaman Islands in 1794, south India in 1800-01 and Nepal in 1802-03.

The extensive years of 1800-34 witnessed much more speedy developments in Botany. Reverend William Carey (1761-1834) established from 1800 onward a significant private garden at Serampore, consisting of trees and some 427 species of plants laid out in the Linnean system.

In the years of 1815-46, Nathaniel Wallich (1786-1854) served as Superintendent of the Calcutta Botanical Gardens. In 1834, he made the significant verification that an Assamese scrub sent to him was a genuine tea plant, thus establishing the existence of a domestic Indian tea culture. In 1835, Wallich joined William Griffith (1810-1845) and John McClelland (1800-1883) to explore Assam for a site capable of growing tea. Throughout his many long tours Wallich gathered an extensive collections of plants in Nepal, Assam, Penang and Singapore. From these collections he prepared Plantae Asiaticae Rariores (1830-32) and Tentamen Florae Nepalensls (1824-26).

Developments in Botany were governed by a curious factor that Botanical Gardens were being founded in every significant city, only to chart the escalating growth of botanical specimens. In 1815, George Govan (1787-1865) created the Saharanpur Botanical Garden. He took charge of it after the Nepal War and in 1819-21 was formally named its Superintendent. The garden`s mission embraced the growth of plants and trees needing this locale`s cooler more European-like climate. Govan was succeeded as superintendent by John Forbes Royle (1823-31) and Hugh Falconer. At the associated Mussoorie Garden, Royle attempted to grow plants capable of producing drugs for the British East India Company`s medical service.

Within the period of 1826-28, Robert Wight (1796-1872) collected several thousand plant specimens in South India while serving as Naturalist to the Government of Madras. After his retirement in 1853, he presented over 4000 plants to the Royal Botanic Garden, Kew. Wight produced two illustrated works, first of a kind containing lithograph illustrations: Illustrations of Indian Botany (1831) and Icones Plantanun Indiae Orientalis (1840-53).

In the time period of 1832-42, after serving as Superintendent of the Saharanpur Gardens, Hugh Falconer (1808-1865) became Superintendent of the Calcutta Botanical Gardens from 1847 to 1855. Here, he restored numerous palm trees and scrubs to the garden, introduced cinchona from South America and implemented conservation measures for the teak forests of Tenasserim, Burma.

Botanical developments and further research work were being extensively looked at, with the educated British elite bottling out fresh kinds of ideas every other day. On such an occasion, in the times of 1832-45, William Griffith excelled as a collector of mammals, fishes, insects and especially of plants from Afghanistan to Malacca. He examined not only their classification but also their morphology. From his study came: Icones Plantarum Astaticarum (1847-54), Notulae ad Plantas Aslaticas (1847-54), and Palms of British India (1850). While Acting Superintendent of the Calcutta Botanical Gardens (1842-44) he reversed many of Wallich`s Linnean arranged gardens for those ordered according to the Natural System.

Within the years of 1842-61, Thomas Thomson (1817-1878) joined a boundary commission determining the border between Kashmir and Tibet during which he collected plants of the Himalayas. In 184, he joined Sir Joseph Hooker (1817-1911) in exploring the botanic resources of the Himalayas. From his travels Thomson published Western Himalaya and Tibet (1852) then joined Hooker in the production of Floria Indica (1855). Thomson served as Superintendent of the Calcutta Botanical Gardens from 1855 to 1861.

Within the prolonged period of 1847-51, Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker travelled widely in the Himalayas, Eastern Bengal and the Khasi Hills collecting plants. From these tours he prepared: The Rhododendrons of Sikkim Himalaya (1849), Himalaya Journal (1854), and The Flora of British India (1872-96). Later in 1855-85, Hooker served as the Assistant Director, then Director of the Royal Botanic Garden, Kew, where he received and incorporated in the Kew collections many Indian plants. Developments in Botany had earned a full-circle status, with unexplored domains coming to light under exhaustive research work and surveys, which were later jotted down as treatises.

Within the years of 1857-82, Richard Henry Beddome (1830-1911) collected several thousand plants, especially ferns, while serving as an Assistant Conservator and later Head of the Madras Forest Department. Several publications emerged from his work including: Ferns of Southern India (1862), Trees of the Madras Presidency (1863), Ferns of British India (1865-70), Icones Plantarum Indiae Orientalls (1868-74), Flora Sylvatica for Southern India (1869-73) and Handbook to Ferns of British India (1883).

Within the span of 1861-1868, Thomas Anderson (1832-1870) was named Superintendent of the Royal Botanical Gardens, Calcutta. In 1864 he took on additional responsibility for the Bengal Forest Department. Much of his garden stock was devastated by cyclones in 1864 and 1867.

Within the span of 1861-1868, Thomas Anderson (1832-1870) was named Superintendent of the Royal Botanical Gardens, Calcutta. In 1864 he took on additional responsibility for the Bengal Forest Department. Much of his garden stock was devastated by cyclones in 1864 and 1867.

During the years of 1869-1878, Charles Clarke, 1st Baron (1832-1906) succeeded Anderson as the superintendent of the Calcutta Botanical Gardens. He pioneered the application of phyto-geographical organisation to Indian botany. In support of this school of thought, Clarke published Compositae Indicae (1876) and A Class-Book of Geography (1878). These small incidents were instances enough to add up to substantial developments in Botany and experimentations and discoveries from rich floral collection gradually being uncovered.

In the years of 1871-1898, Sir George King (1840-1909) was appointed Superintendent of the Royal Botanical Gardens, Calcutta. King eschewed the former scientific layout for the garden replacing it with an aesthetic design of curved walks and undulating hillocks. He provided glasshouses, a conservatory and numerous pools. In 1887 he initiated the publication of The Annals of the Royal Botanic Garden, Calcutta. In 1890 with the establishment of the Botanical Survey of India, King became its first Director. He was equipped with the mission to explore the flora of the whole of India, to oversee all botanical research and to coordinate the work of the other official botanic gardens at Saharanpur and Ootacamund (Ooty).

In 1885, Dr. David Douglas Cunningham (1843-1914) carried out mycological research at the Medical College of Calcutta regarding fungus diseases on India. These efforts represent the first applications of laboratory research to Indian botany. Botanical developments had become a regular work of the day in British Indian administration, with the turn of the century witnessing heightened advancements and sophisticated implemental application.

During the years of 1886-97, Sir David Prain (1857-1944) became Curator of the Calcutta Herbarium. Then he succeeded King in 1898 as Director of the Royal Botanic Garden. In this post, he displayed a special interest in economic botany. In 1905 Prain became the Director of the Royal Botanic Garden at Kew, England.

During the span of 1875-1903, John Firminger Duthie (1845-1922) was named Superintendent of the Saharanpur Garden. With interests in economic botany he specialised in the study of grasses due to the need for fodder in Northwest India. Duthie published Flora of the Upper Gangetic Plain.... (1903).

The upcoming phase of 1880s to 1910s, saw developments in Botany marked by a period of publication of Hooker`s Flora of British India in seven volumes and a range of regional and local flora studies: Theodore Cook`s Flora of the Bombay Presidency (1903), Sir David Prain`s Bengal Plants (1903) and Sir Henry Collett`s Flora Simlensis (1902).

In 1921, A. F. R. Wollaston while serving as the Medical Officer and Naturalist to a Mount Everest expedition collected numerous species of plants found in the Himalayan region. These species were later presented to the Royal Botanic Garden at Kew, England.

Within the period of 1933-1950, Frank Ludlow (1885-1972) and George Sherriff (1898-1967) conducted numerous tours collecting plants in Bhutan and south-eastern areas of Tibet. For the first time many of these plants were photographed in situ, crated and flown to England. Their collection of some 21,000 specimens now resides in the British Museum (Natural History).