Dakhni Muslims are referred to as the Dakhni Urdu-speaking Muslims. The word `Dakhni` has been derived from the word, `Deccani` or one who belonged to the Deccan region of South India. The had more in common with their co-religionists in other parts of South India, like the Urdu-speaking Muslims of Bangalore, Hyderabad, and Maharashtra, and, in lesser ways, with the Urdu-speaking Muslims of north India. Dakhni Muslims were further subdivided into the Sunni and Shiah sects. `Dakhni Muslim` itself is an umbrella category, which covers intra-cultural divisions based on the origin myths of the different groups such as the Navayats, Syeds, Sheikhs, and Pathans.

Where these intra-cultural divisions between the Navayats, Syeds, Sheikhs and Pathans took on relevance was in their consistent endogamy for a large part of the twentieth century. This endogamy was redefined as Dakhni endogamy where the main criterion for marital ties between families became the language spoken among them. They rarely inter-married with any Tamil-speaking Muslims. This meant that they permitted inter-marriage between Dakhni Urdu-speaking families unmindful of the earlier intra-cultural divisions. There are, however, exceptions to this practice. The Navayats, for example, were known to rest their claim to purity of descent on an endogamous pattern of marital alliance. Again, the Syeds, for instance, rarely inter-married with Pathans. Dakhni endogamy can be explained partly in terms of the concern for purity of descent. In present-day Tamil Nadu, such endogamy is explained more empathically as a consequence of a crucial concern for language and, deriving from it, the differences in customs and social milieux between Tamil and Urdu speakers.

Among all these divisions within the Dakhnis, the ones those are significant politically are the differences between the Sunni sect and the Shia sect, who had separate mosques, seminaries, theologies, government kazis, and community organizations. Unlike the differences between Sunnis and the Shiahs of Lucknow, which often resulted in violent clashes, these sects in Tamil Nadu enjoyed cordial relations with each other. Whatever their doctrinal differences, they came together in asserting a common Islamic identity whenever they perceived the convergence of their interests. This convergence was facilitated by the fact that both groups were Urdu speakers, part of a linguistic minority among the larger religious society of Tamil speakers. Some Shiahs came to be accepted as leaders of the larger south Indian Muslim community and represented the interests of both Sunni and Shiah Muslims. It must be recognized, however, that the Shiah-Sunni divisions mattered only to Dakhni Urdu-speaking Muslims and were irrelevant to the larger Muslim population of Tamil speakers.

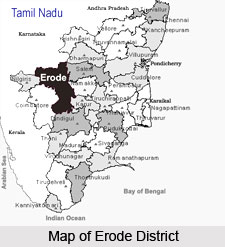

The arrival of the Dakhnis, dated to the time of the invasion of the Bahmani Sultans in the sixteenth century, was significant in two ways. The northern parts of Tamil Nadu where they settled recorded a substantial increase in the Muslim population. Here the Tamil Muslim population was small. The Dakhnis introduced to Tamil Nadu Islamic religious and linguistic traditions strongly influenced by the customs of the north Indian Muslims. The cultural differences that separated them for their Tamil-speaking co-religionists have been perceived as causing political divisions among the region`s Muslims.

While the divide between Tamil and Urdu-speaking Muslims was a very important factor in the politics of the Muslims of Tamil Nadu, it would be simplistic to reduce all politics of Muslims to cultural conflict. Larger determinants of identity formation were the political processes in the Tamil region across the twentieth century, which determined whether the Tamil and Urdu Muslims conflicted or co-operated with each other.

Tamil and Dakhni Muslim groups did not encourage inter-marriage, and differed in their kinship patterns and their respective social structures. However, both shared common ritual spaces and a Sufi tradition. If marriage, kinship, and social structure, besides language, were the main sources of differentiation between them, then ritual space and the Sufi tradition were the sources of commonality or unity between them.

The Dakhni Muslims or the Urdu-speaking Muslims settled in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. They constituted influential political elite in Tamil Nadu state between the sixteenth and the eighteenth centuries. With increasing British influence in the region, the Nawab of Arcot was reduced to a pensioner and a figurehead, and the power, privilege, and social position of Dakhni Muslims declined. By the late nineteenth century, the Dakhnis were among the first in south India to take the Deoband and Aligarh movement. If the claim for reservations in the state services and education in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was any indicator of a political awakening among the Muslims of Tamil Nadu, then the Dakhnis were the earliest in leading the `community`. The Dakhni elite, like the Tamil Brahmin, were the first to join the bar, the teaching profession, and the bureaucracy. These professions restored to those who succeeded in joining them their sense of power and social position. From their ranks were drawn the proponents of pan-Indian Islam in the region. By contrast, Tamil Muslims, who as merchants and seafarers had relied less on state power and gained more from the maritime trade that accompanied the European expansion, were slower to feel dispossesses. It was only in the early twentieth century that some Tamil Muslims joined the Dakhni elite on the political bandwagon of pan-Indian Islam.

Apart from Dakhni attempts to maintain their traditional social position, their dominance was also facilitated by colonial discourse. British impressions of Muslims in Tamil Nadu were shaped by the ruling elite composed of Persianized nawabi courtiers and Dakhni Muslims. While the British encountered Tamil-speaking Muslims on the coast and trading marts, they saw in the Dakhni elite their image of the `pure` and `real` Muslim, mirroring their experience of the Urdu Muslim elite of north India. The British categorized all Tamil speakers as to the Dakhni elite. This understanding was to find political expression in their appointments of kazis to the Muslim communities, where Muslims who knew Persian and Urdu were deemed more suitable and were preferred to those who were proficient in Tamil and Arabic.

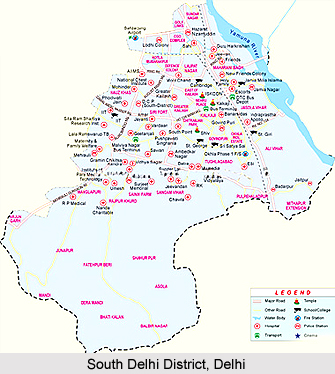

Further, since the Dakhnis had settled in a belt around Chennai city, they were highly visible to colonial administrators compared to the more populous Tamil Muslims, who were concentrated in the southern districts of Tamil Nadu. Their proximity to the city of Chennai gave the Dakhnis relatively easier access to Fort St. George as well as to the politicians at its court.