In the ancient Tamil country the art of painting was quite eminent even before the Chola Dynasty ruled. Ancient Tamil literary text Nedunalvatai, Akananuru and Paripadal were written in the second and third century. These texts mention about beautiful mansions and places that have rooms painted on the themes based on mythology. They are either flat surface paintings or paintings accentuated on stones or stucco bas relief. Few of the paintings have a protective coating of lacquer which is know as mezhuguchey padam in Tamil. Pattinapalai by Urutirankannanar particularly reveals about the mansions of the Chola ports named Kaveripoompattinam. These ports are fabricated with exclusive paintings but these paintings are not any more available. In the later centuries the rulers of Chola Dynasty, Pallava Dynasty and Pandya Dynasty unveiled the best skills of their artisans to boost various forms of art.

In the ancient Tamil country the art of painting was quite eminent even before the Chola Dynasty ruled. Ancient Tamil literary text Nedunalvatai, Akananuru and Paripadal were written in the second and third century. These texts mention about beautiful mansions and places that have rooms painted on the themes based on mythology. They are either flat surface paintings or paintings accentuated on stones or stucco bas relief. Few of the paintings have a protective coating of lacquer which is know as mezhuguchey padam in Tamil. Pattinapalai by Urutirankannanar particularly reveals about the mansions of the Chola ports named Kaveripoompattinam. These ports are fabricated with exclusive paintings but these paintings are not any more available. In the later centuries the rulers of Chola Dynasty, Pallava Dynasty and Pandya Dynasty unveiled the best skills of their artisans to boost various forms of art.

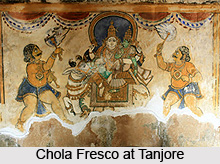

Most of the exquisite paintings of the Cholas are found in their grandest monument, Brihadeeswarar temple. These paintings were found in the lower circumambulatory passage or prakara. They were painted in the inner wall, over the pilasters and ceilings and in the inner side of the outer wall. Few of their paintings have also been traced in Narthamalai and Malayadipatti which have been well preserved till date.

Many centuries back the Nayak kings used to sponsor for the Chola paintings and frescoes. These paintings were discovered in the 1930`s when some of the Nayak paintings had crumbled that revealed the Chola masterworks. These Nayak Paintings of the seventeenth century are still noticeable in the main shrine of the Brihadeeswara temple and in other additional shrines.

Techniques of Chola Murals

Chola Paintings have been brilliantly executed and the colours and modeling used for the paints are awe inspiring. The different sizes of the images that are painted also remark about the judgments of the artists. The walls that bear the paintings are usually eight feet high and fourteen feet wide. The clearance in front is seven to eight feet. The paintings have adopted the complex method of the fresco style. This requires great skills and finesse by the artisans. The artisans first apply a coarse layer on the granite walls which is about 1.8 mm thick. It is evenly spread on the walls. They also used a rough stone to enable the plaster to adhere better. Another fine layer of plaster is later spread over it which is almost 0.7 mm thick. While the second layer is still wet, the artist promptly sketches the outline and puts the colours on the wet plaster. The colors are organic and to derive the perfect shade they are mixed with water.

Chola Paintings have been brilliantly executed and the colours and modeling used for the paints are awe inspiring. The different sizes of the images that are painted also remark about the judgments of the artists. The walls that bear the paintings are usually eight feet high and fourteen feet wide. The clearance in front is seven to eight feet. The paintings have adopted the complex method of the fresco style. This requires great skills and finesse by the artisans. The artisans first apply a coarse layer on the granite walls which is about 1.8 mm thick. It is evenly spread on the walls. They also used a rough stone to enable the plaster to adhere better. Another fine layer of plaster is later spread over it which is almost 0.7 mm thick. While the second layer is still wet, the artist promptly sketches the outline and puts the colours on the wet plaster. The colors are organic and to derive the perfect shade they are mixed with water.

Lime is used for white, lamp black for black, ultramarine for blue, ocheres for yellow, red and brown, terre verte for green and various mixtures for others colours. Pigments that are sensitive to alkalies are avoided since they react with the base. Despite the limited palette the Cholas artists have excelled themselves. The advantage here is that the pigments penetrate the surface as the water and calcium hydroxide in the plaster evaporate, react with the air and create a smooth, glassy protective surface over the murals. The genius of the artist lies in choosing pigments that will not react adversely with the lime and in executing his work swiftly and correctly - mistakes will mean scrubbing out the plaster and starting the painting on the entire wall all over again. The artist must clearly have the final picture in mind and remember that the colour will fade with time. Colours are also used to represent distance. In the Brihadeeswarar Temple, not only did the artist handle the large areas with great ease they also managed tougher pilasters and stone joints just as well. The Chola paintings that one sees today are both of secular and religious themes. The south side of the western world has the most complete and chronologically arranged paintings. The three panels here depict the episodes in the life of Saint Sundarar or Sundaramati Nayar an eighth century Nayanmar. The Nayanmars were the saint who played an important role in the Bhakti Movement in the medieval India. There are sixty three prominent leaders around them and Sundarar is regarded as one of the four most prominent Nayanmars.