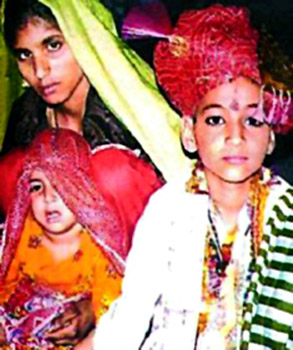

Child marriage in modern India was a much debated and publicised issue. A focus on this issue is particularly significant because it is the first social reform issue in which organized women played a major role in both the development of arguments, in this case against child marriage, and the work of political petitioning. In fact the development of the various Indian women`s national organizations, their efforts to cooperate with one another, and their relationships with Indian males, British officials, and British women can be viewed through the issue of child marriage in the second half of the 1920s.

Child marriage in modern India was a much debated and publicised issue. A focus on this issue is particularly significant because it is the first social reform issue in which organized women played a major role in both the development of arguments, in this case against child marriage, and the work of political petitioning. In fact the development of the various Indian women`s national organizations, their efforts to cooperate with one another, and their relationships with Indian males, British officials, and British women can be viewed through the issue of child marriage in the second half of the 1920s.

The issue of child marriage had for long remained a thorny issue in British India. The British missionaries and officials expressed their horror of pre-puberty marriage which many Indians explained as only the first marriage to be followed by the Garbbadhan (consummation) ceremony immediately after the attainment of puberty. In 1860 the criminal code set the age of consent for both married and unmarried girls at ten years. The issue reappeared in the 1880s and in 1891 the criminal code was amended to raise the age of consent to twelve years. This meant that the age of the female when the marriage was consummated could now be publicly questioned, a definite proof that the British were carrying out their civilising mission in India. However, there were no convictions under the Act until thirty years later. By then there were new reasons to re-examine the age of marriage in India.

Legislations Regarding Child Marriage

The revival of interest in the age of marriage and age of consent was an outcome of the discussions in the League of Nations. The concern with traffic in women and girls led to consideration of the age of consent and ultimately to proposals in the Indian Assembly. Various bills addressing these questions were introduced and defeated until 1927 when Rai Sahib Harbilas Sarda introduced his Hindu Child Marriage Bill. During this time, there was also a scathing attack posed on the custom of child marriage in India by an American journalist, Katherine Mayo. Mayo berated Indians for their treatment of women of all ages and concluded that social customs accounted for the weakness of the Indian race and made it clear that these people were not ready to "hold the reins of Government." Eager to escape blame, government officials began telling the Assembly that they supported beneficent social legislation.

Work done by Women`s Organisations for Child Marriage Restraint Act/Joshi committee

The Assembly referred Sarda`s bill to a select committee of ten chaired by Sir Morophant Visavanath Joshi. The committee included only one Indian woman, Mrs. Rameshwari Nehru, recommended by the Women`s Indian Association. Once appointed, the committee moved quickly to assess public attitudes; they sent out 8,000 questionnaires and announced a tour to hear testimony from a wide range of witnesses. The women`s organizations promoted this legislation at every stage. They generated propaganda against child marriage, commented on proposed bills, petitioned, met with the Joshi Committee, lobbied to secure passage of the Child Marriage Restraint Act, and worked, after its passage, for registration of births and marriages and other legislation to make it a meaningful Act.

The Assembly referred Sarda`s bill to a select committee of ten chaired by Sir Morophant Visavanath Joshi. The committee included only one Indian woman, Mrs. Rameshwari Nehru, recommended by the Women`s Indian Association. Once appointed, the committee moved quickly to assess public attitudes; they sent out 8,000 questionnaires and announced a tour to hear testimony from a wide range of witnesses. The women`s organizations promoted this legislation at every stage. They generated propaganda against child marriage, commented on proposed bills, petitioned, met with the Joshi Committee, lobbied to secure passage of the Child Marriage Restraint Act, and worked, after its passage, for registration of births and marriages and other legislation to make it a meaningful Act.

Throughout the country the All India Women`s Conference branches organized meetings at which women`s opinions could be expressed. In their speeches women condemned Child Marriage as one of many customs that "crushed their individuality and denied them opportunities for education and development of mind and body. Women agitating against the custom of child marriage had begun to question the whole system including their socialization into it. However, the radical statements that were made here rarely found expression in the more carefully considered petitions and resolutions delivered to government officials.

When the members of the AIWC met with the Joshi Committee they refuted the claim that women were in favour of a youthful marriage, that later marriages would lead to immorality, that all men supported child marriage, and that child marriage was a part of Vedic religion. The AIWC did not address the issues of when to marry, whom to marry and so on as they felt that all this was a matter of individual right. They simply argued for the fact that marriage in a woman;s life should come at a biologically appropriate age when she would be able to handle her responsibilities.

Passing of the Child Marriage Restraint Act

The Joshi Committee recommended fifteen as the minimum age of marriage with twenty-one the age of consent. British officials make it clear they felt they had no option but to support this measure. Had they not supported it, the charge of reformers and nationalists - that foreign rule inhibited social reform - would gain credence. But the final measure was a compromise, the minimum age of marriage for females was set at fourteen, for males eighteen, and the age of consent was not mentioned. Passed at the beginning of October 1929, the Act took effect in April 1930.

Outcome of the Child Marriage Restraint Act

The women`s organizations rejoiced when the Sarda Act was passed. The NCWI was the most cautious in its praise saying this was the first campaign in the battle against social evils, but not a victory. The WIA was less hesitant and immediately called a meeting to congratulate Rai Sahib Harbilas Sarda. The Sarda Act, in their view, was the major achievement of 1929. The AIWC reacted the most positively, calling the Sarda Act a "great achievement" and a "personal triumph."

The women`s organizations rejoiced when the Sarda Act was passed. The NCWI was the most cautious in its praise saying this was the first campaign in the battle against social evils, but not a victory. The WIA was less hesitant and immediately called a meeting to congratulate Rai Sahib Harbilas Sarda. The Sarda Act, in their view, was the major achievement of 1929. The AIWC reacted the most positively, calling the Sarda Act a "great achievement" and a "personal triumph."

However, the celebrations proved to be short-lived. The commitments of the Government to a rigid enforcement of the law underwent a rapid decline when they realised that a lot of the opposition was coming from the Muslim communities. Muslim leaders had threatened "formidable agitation" even before the Act was passed. Following its approval they threatened to break the Sarda Act by joining with Mahatma Gandhi and the Congress in their anti-government campaign. The British did not want to se how far this threat would go. Muslim leaders asked that the Act be amended to exclude Muslims. The women`s organizations tried to combat this move in a number of ways. The AIWC claimed they spoke for all women in India and Muslim women members of the organisation even presented a memorial to the viceroy stating their opinion.

However, the government did not do much to amend or repeal the Act. More than the pressure of the women`s organisations it was the fear of world opinion and the need for political consistency that made them adopt this stand. British officials were aware an amendment would suggest weakness. Moreover, the subject was one that was being much attention to by the League of Nations. So they decided that the best way was to leave it alone.

Enforcement of the Act was practically non-existent. It was difficult to make a charge and difficult to obtain a guilty verdict. Moreover, many of those found guilty were pardoned. The number of child marriages increased as there was a rush to celebrate marriages before the Act came into effect. The government blamed reform-minded Indians for not personally supporting the Act and not doing more to educate the masses about the evils of child marriage. Indian reformers blamed the government.

The Child Marriage Restraint Act had a profound effect on the women`s organizations. It was a consensus issue and this made it easy for women from different regions and communities to work together and for the three national organizations to coordinate their activities. As the Joshi Committee travelled throughout India it heard arguments against child marriage presented by numerous women. It was these women who made it clear that India had its share of educated, articulate women who understood the problems of their country and had formulated answers.