Chera dynasty in Kerala flourished before the Sangam era and it lasted till the twelfth century A.D. With the Pandyas of Madurai and the Cholas of Kanchipuram, the Cheras formed a triarchy of Dravidian ruling houses whose rival claims kept South India in a state of intermittent warfare for more than a thousand years. The Chera kings, the first known rulers of Kerala, were by origin of Nair, not Kshatriya caste, as is clearly shown by their being classed in the Sanskrit epics as of degenerate race, outside the recognized caste system. Nothing is known of the origins of the Chera dynasty which long ago defended the mountain barriers of a kingdom that covered very much the same ground as modern Kerala, but something of the nature of their culture may be gleaned from the references in the great Hindu epic, the Ramayana, where the Cheras are classed, along with Greeks and Nakas, among those degraded races who illustrate the degeneracy of the age of Kali Yuga.

Chera dynasty in Kerala flourished before the Sangam era and it lasted till the twelfth century A.D. With the Pandyas of Madurai and the Cholas of Kanchipuram, the Cheras formed a triarchy of Dravidian ruling houses whose rival claims kept South India in a state of intermittent warfare for more than a thousand years. The Chera kings, the first known rulers of Kerala, were by origin of Nair, not Kshatriya caste, as is clearly shown by their being classed in the Sanskrit epics as of degenerate race, outside the recognized caste system. Nothing is known of the origins of the Chera dynasty which long ago defended the mountain barriers of a kingdom that covered very much the same ground as modern Kerala, but something of the nature of their culture may be gleaned from the references in the great Hindu epic, the Ramayana, where the Cheras are classed, along with Greeks and Nakas, among those degraded races who illustrate the degeneracy of the age of Kali Yuga.

As per the legend of the creation of the state of Kerala by Parasurama; Parasurama, having planted the sixty-four joint families of Brahmin as the seeds of Keralan villages, gave them laws and institutions to govern themselves, But, like modern Malayalis, the Brahmins found it impossible to agree, and their primeval republic declined into chaos. Parusurama, however, had been prudent enough to advise them, if they could not rule themselves, to invite kings from outside the country, and thus began a line of monarchs called the Perumals. These Perumals or the king rule for a period of twelve years and after the end of the stipulated period, the physical sacrifice of the king takes place. Cheraman Perumal appears to have been, not a personal name, but a title held by the kings of the whole Chera dynasty, lasting from before the Chrostoam era long into the twelfth century, and it is possible that all members of the line, after reining a set number of years, performed such an act of renunciation. Until the sixteenth century, when the Portuguese stopped it, a similar custom survived among the Rajas of Cochin, who claimed descent from the Cheras.

Perumchottu Utiyan Cheralatan was the first Chera ruler, who holds the credit of founding the Chera dynasty. His son, Imayavaramban Nedum Cheralatan succeeded him, who worked hard to make the dynasty more powerful in all the areas. The reign of Imayavaramban also witnessed great development in the field of literature and art since the king patronized culture and art very much. Kannanar was his poet laureate. Kadalpirakottiya Vel Kelu Kuttuvan is however, regarded as the most famous ruler of the Chera Dynasty, whose reference is given in the epic, Shilappadikaram.

Perumchottu Utiyan Cheralatan was the first Chera ruler, who holds the credit of founding the Chera dynasty. His son, Imayavaramban Nedum Cheralatan succeeded him, who worked hard to make the dynasty more powerful in all the areas. The reign of Imayavaramban also witnessed great development in the field of literature and art since the king patronized culture and art very much. Kannanar was his poet laureate. Kadalpirakottiya Vel Kelu Kuttuvan is however, regarded as the most famous ruler of the Chera Dynasty, whose reference is given in the epic, Shilappadikaram.

Since these references mention peoples like the Sakas who reached India in the first century B.C., they were obviously interpolated relatively late into the constantly changing structures of the epics, not finally stabilized until about the 1tli century A.D. But at least they establish that round about two thousand years ago, when Greek and Saka invaders were still active in northern India, the Cheras (and here the references seem to imply a whole people rather than a mere dynasty) were known and were clearly so different in character from the Indo-Aryans of the North that they were not yet regarded as having the true part in the fabric of Hindu religion and custom.

The trade and commerce of Kerala, at least in terms of commodities, always tended to be a one-way traffic; even in the days of the Greeks the principal imports were luxury items for the use of the small ruling class, and the ancient kings of the Chera dynasty and their merchants demanded mostly solid Roman coin in exchange for their goods, so that in the first century A.D. Pliny complained of the impending ruin of Rome through the drain of currency to India in order to satisfy the Roman demand for luxuries. The pattern established two thousand years ago continues; Kerala is still one of the principal exporting and cash-earning regions of India. Only one Indian in twenty-five lives in the state, but its people earn approximately an eighth of the country`s precious supply of foreign exchange by selling the products of plantations, coconut groves and of the little peasant holdings where pepper and ginger are grown. This makes all the more ironical the fact that another of the claims of the state of Kerala to distinction is that the average income of its people is well below the level for India as a whole.

A negative result of the traditional emphasis of Kerala on crops for foreign trade is the fact that for centuries it has suffered from shortage of rice, the favourite food of the Malayalis. Food crises are nothing new on the Malabar Coast. As long ago as the sixteenth century the Zamorin of Kalikod (Calicut) was importing rice to feed his people, and on one occasion when the Portuguese destroyed a flotilla of his grain ships a minor famine was only narrowly averted. Then, as now, the Malayali farmers were already concentrating on growing spices for the foreign market rather than food for themselves.

A negative result of the traditional emphasis of Kerala on crops for foreign trade is the fact that for centuries it has suffered from shortage of rice, the favourite food of the Malayalis. Food crises are nothing new on the Malabar Coast. As long ago as the sixteenth century the Zamorin of Kalikod (Calicut) was importing rice to feed his people, and on one occasion when the Portuguese destroyed a flotilla of his grain ships a minor famine was only narrowly averted. Then, as now, the Malayali farmers were already concentrating on growing spices for the foreign market rather than food for themselves.

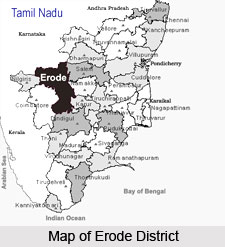

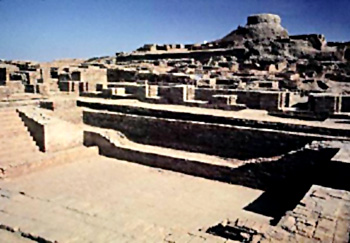

The Chera kings and their conquests lead into the political history of ancient Kerala, a subject which belongs to the next doms, and the next stage in the ethnic history of Kerala is the arrival of the Dravidians, generally regarded as the descendants of the dark Mediterranean people who once ruled all of north India and who established the Indus Valley Civilization, with its centers at Mohenjo Daro and Harappa, round about 2500 B.C. A thousand years or more lately the Indo-Aryans, with their Vedic Religion and their modernized military tactics based on the war chariot, which came riding over the Hindu Kush and destroyed the ancient cities of the Indus. By 1000 B.C. their dominion over the Punjab and the great plain of the Ganga River and the Yamuna River was complete. Those of the Dravidians who did not remain to become serfs to the conquerors retreated east into Bengal, where eventually they lost their language but retained their physical characteristics, or south beyond the Vindhya mountains into the part of India which forms Andhra Pradesh, Mysore, Chennai and Kerala.

Those of the Dravidians who did not remain to become serfs to the conquerors retreated east into Bengal, where eventually they lost their language but retained their physical characteristics, or south beyond the Vindhya mountains into the part of India which forms Andhra Pradesh, Mysore, Chennai and Kerala.

The devolvement of authority by the Chera kings is suggested in the references in Shilappadikaram, to the `king`s council` and the `five assemblies`. Shilappadikaram is a literary epoch which was written by Ilango Adigal, King Cheran Chenguttuvan`s brother. There are several references to a number of legends from the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and the Puranas. It narrates the history of the Chola, Chera and Pandian kingdoms. The Chera king`s council consisted of the inner group of respected elders and of powerful noblemen, rajas of districts like the `ruler of Alumbil`, who on one occasion makes a speech full of wise advice; the council was not merely the highest advisory body, but also the final judicial tribunal which assisted the king when he held his daily durbar to consider petitions and render judgments.

The role of the `five assemblies` in the ancient Chera kingdom is not clearly defined. But it is likely that the Chera Kingdoms were territorially organized. There were four divisions of the Chera kingdom proper, the northernmost beginning in the neighbourhood of Cannanore and the southernmost near Trivandrum. Trivandrum itself was part of the realm of the mysterious Ay kings who ruled up to the tenth century A.D. in the region later known as South Travancore, between Trivandrum and Cape Comorin, with their capital at Vijinjam, once a flourishing port but today a dejected fishing village. During the Sangam Age the Ay kings, later independent, seem to have been tributary to the Cheras, so that there would in practice be five divisions to the empire, and five assemblies, who were presumably elected by the Nair warriors, since they are mentioned in connection with the army.

Even if the Cheras possessed their own religion, a considerable number of various other religious traditions were there during the rule of the Cheras. Jainism and Buddhism were introduced in the Indian state of Kerala by the second century BC.