Chennakesava temple was originally called Vijayanarayana Temple. Chennakesava means "handsome Kesava" and is a form of Lord Vishnu. This temple is dedicated to Lord Vishnu. Also, known as Keshava Temple of Belur, it is a 12th-century Hindu temple located in Hassan district of Karnataka. The temple was accredited by King Hoysala Vishnuvardhana in 1117 CE. The main entrance to the complex is crowned by a Rayagopura that was built during the rule of Vijayanagar Empire. The pillar facing the main temple, the Garuda sthambha was built in the Vijayanagar period while the pillar on the right, the Deepa sthambha is a contribution of Hoysala period. There are three entrances and the doorways have decorated sculptures of doorkeepers on either side.

Chennakesava temple was originally called Vijayanarayana Temple. Chennakesava means "handsome Kesava" and is a form of Lord Vishnu. This temple is dedicated to Lord Vishnu. Also, known as Keshava Temple of Belur, it is a 12th-century Hindu temple located in Hassan district of Karnataka. The temple was accredited by King Hoysala Vishnuvardhana in 1117 CE. The main entrance to the complex is crowned by a Rayagopura that was built during the rule of Vijayanagar Empire. The pillar facing the main temple, the Garuda sthambha was built in the Vijayanagar period while the pillar on the right, the Deepa sthambha is a contribution of Hoysala period. There are three entrances and the doorways have decorated sculptures of doorkeepers on either side.

History of Chennakeshava Temple

The history of the Chennakeshava Temple in Belur, Karnataka, is deeply intertwined with the Hoysala dynasty, a prominent South Indian ruling dynasty that thrived between 1000 CE and 1346 CE. During this period, the Hoysalas exhibited a remarkable fervor for temple construction, erecting approximately 1,500 temples across 958 centers. Belur, known as Beluhur, Velur, or Velapura in ancient inscriptions and medieval texts, held a special significance as the early capital of the Hoysala kings. It was a city esteemed to such an extent that it was often referred to as the "earthly Vaikuntha" (the abode of Lord Vishnu) and "dakshina Varanasi" (the southern holy city of Hindus) in later inscriptions.

One of the illustrious Hoysala monarchs, King Vishnuvardhana, ascended to the throne in 1110 CE. In 1117 CE, he commissioned the construction of the Chennakeshava Temple, dedicated to Lord Vishnu. This temple is considered one of the "five foundations" of his enduring legacy. Regarded by scholars of Indian temple architecture and history, such as Dhaky, as a pinnacle of architectural brilliance, this temple reflects not only the rising opulence of the Hoysala dynasty but also the profound spiritual dedication to Sri Vaishnavism, inspired by the teachings of Ramanujacharya. The main temple was initially named Vijaya-Narayana, while the smaller temple built by King Vishnuvardhana`s queen, Santala Devi, was referred to as Chennakesava in the inscriptions of the era. However, in contemporary times, these two temples are collectively known as the Chennakeshava Temple and Chennigaraya Temple, respectively.

The Chennakeshava Temple in Belur achieved completion and was consecrated in 1117 CE, although the complex continued to expand over the subsequent century. King Vishnuvardhana later shifted his capital to Dorasamudra, also known as Halebidu, renowned for the Hoysaleswara Temple dedicated to Lord Shiva. The construction of the Hoysaleswara Temple persisted until the demise of King Vishnuvardhana in 1140 CE. His legacy was carried forward by his descendants, who completed the Hoysaleswara Temple in 1150 CE, as well as other temples, notably the Chennakesava Temple in Somanathapura, situated approximately 200 kilometers away, which was completed in 1258 CE.

However, the Hoysala Empire, along with its capital, faced adversity in the early 14th century when it was invaded, plundered, and ultimately destroyed by Malik Kafur, a commander under the rule of Alauddin Khalji, the ruler of the Delhi Sultanate. Belur and Halebidu endured similar fate in 1326 CE when they became the target of plunder and destruction by another Delhi Sultanate army. Subsequently, the territory came under the rule of the Vijayanagara Empire. The Hoysala architectural style gradually waned in the mid-14th century following the demise of Hoysala King Veera Ballala III in a war against the Muslim Madurai Sultanate, along with his son. This marked the end of an era that had seen the flourishing of Hoysala temple architecture and its unique Karnata Dravida tradition.

Inscriptions in Chennakeshava Temple

The Chennakeshava Temple in Belur boasts a total of 118 inscriptions discovered within the temple complex. These inscriptions span from 1117 CE to the 18th century, serving as invaluable historical records that shed light on various aspects of the temple`s journey through time. An inscription located on the eastern wall near the north entrance of the temple`s main mandapa (hall) stands as evidence to the temple`s origins. It reveals that Kin`Vishnuvardhana commissioned the temple in 1117 CE, dedicating it to God Vijayanarayana.

Simultaneously with the main temple, the Chennigaraya temple was constructed, with the queen providing patronage for its creation. Contributions to the temple`s maintenance and operation were made by Narasimha I of the Hoysala dynasty, demonstrating the ongoing commitment to the temple`s prosperity.

In 1175 CE, Ballala II made notable additions to the temple complex. This included the construction of temple buildings for the kitchen and grain storage in the southeast corner, as well as the establishment of a water tank in the northeast corner of the temple premises.

Initially, the temple lacked a boundary wall, and the main mandapa was open for devotees to witness the intricate carvings inside. However, to enhance the temple`s security, a high wall was erected around it. Additionally, a wood-and-brick gateway and doors were added under the supervision of Somayya Danayaka during the rule of Veera Ballala III (1292–1343). To preserve the temple`s sanctity, the open mandapa was adorned with perforated stone screens. Although these screens dimmed the interior, they allowed sufficient light for devotees to behold the garbha griya. The temple endured hardships, as it was raided, damaged, and its gateway was set ablaze during an incursion led by the Muslim general Salar, who served under Muhammed bin Tughlaq (1324–1351).

The Vijayanagara Empire played a pivotal role in the temple`s restoration, particularly under the patronage of Harihara II (1377–1404). During this period, several significant additions were made, including the installation of four granite pillars in 1381, the addition of a gold-plated kalasa to a new tower above the sanctum in 1387 by Malagarasa, and the construction of a new seven-story brick gopuram in 1397 to replace the previously destroyed gateway. Moreover, shrines dedicated to Andal, Saumyanayaki, and other deities, along with the dipa-stambha at the entrance, the Rama and Narasimha shrines, were incorporated during the Vijayanagara Empire era.

The temple`s main tower, or shikara, has been lost over time, with inscriptions indicating that it was originally constructed using a combination of wood, brick, and mortar. It suffered destruction and subsequent rebuilding on several occasions. The temple complex was further expanded during the Vijayanagara Empire`s reign, featuring smaller shrines dedicated to goddesses and the Naganayakana mandapa. Interestingly, these structures were constructed by repurposing the remains of demolished temples in the Belur area.

Subsequently, the temple faced damage as a result of the coalition of Sultanates following the decline of the Vijayanagara Empire. Repairs were initiated in 1709, with subsequent additions in 1717 and 1736. In 1774, during the de facto rule of Hyder Ali on behalf of the Wadiyar dynasty, an officer oversaw the temple`s restoration.

In the late 19th century, the upper tower above the sanctum was removed to safeguard the lower levels, and it was never replaced. In 1935, the temple underwent a significant restoration effort, funded by the Mysore government and aided by grants from the Wadiyar dynasty. During this restoration, the Chennigaraya shrine was reconstructed, new images of Ramanuja and Garuda were added, and various facility improvements and repairs were carried out, ensuring the preservation of this historical and sacred site. These restoration efforts, much like the earlier inscriptions, were meticulously documented in stone to serve as a lasting testament to the temple`s enduring legacy.

Main temple of Chennakeshava

The Chennakeshava Temple`s main edifice is characterized by its distinctive architectural features and design. It adheres to the ekakuta vimana style, representing a single shrine, with dimensions measuring 10.5 meters by 10.5 meters. Notably, this temple seamlessly amalgamates elements from both North Indian Nagara and South Indian Karnata architectural traditions.

The temple is situated atop an expansive and open platform thoughtfully designed to serve as a circumambulatory path encircling the sanctum. A vestibule serves as the link connecting this circumambulatory platform to the mandapa, or the hall of the temple. It is within this temple`s precincts that an abundance of intricate artwork can be observed, both on its exterior and interior surfaces.

A significant feature of the Chennakeshava Temple is its construction upon a jagati, a term signifying a symbolic worldly platform. This jagati provides ample space for circumambulation, known as the pradakshina-patha, allowing devotees to perform a reverential circuit around the temple prior to entering it. Remarkably, the design of the jagati is meticulously aligned with the staggered square layout of the mantapa and the star-shaped shrine, harmonizing with the temple`s overall architectural scheme. This design not only serves practical purposes but also holds profound symbolic significance within the temple`s religious and architectural context.

Architecture of Chennakesava temple

Chennakesava temple is made of soapstone. The plan is fundamentally a simple Hoysala plan that has been built with amazing detail. The basic part of the temple is unusually large in size. The temple is a single shrine design. A large entrance hall connects the shrine to the hall. There are 60 bays of the mandapa. The tower on top of the vimana has dilapidated over time. The temple is built on a platform. There is one getaway of steps that leads to the platform and another set of steps that leads of the mandapa. The platform helps the devotee to do a pradakshina around the temple before entering it. The jagati is constructed in a staggered square design and the shrine is star shaped. Initially it was an open mandapa, however later it was transformed into a closed one that was done by erecting walls with pierced window screens. There are 28 such windows which have star-shaped perforations and bands of foliage, figures and mythological subjects. On one of the screens King Vishnuvardhana and his queen Shanatala Devi are depicted. Another screen depicts the king in a standing posture.

The shrine is at the back of the mandapa. Each side of the vimana has five vertical sections that comprise a large double storied niche in the centre and two heavy pillars on either side. These are rotated about their vertical axis in order to produce a star-shaped plan for the shrine. These bear many ornate sculptures that re of earlier style. Vimana`s shape indicates that the tower above it would have been of the Bhumija style. The Bhumija towers are a type of nagara tower which are curvilinear in shape. This shape is uncommon in pure Dravidian architecture.

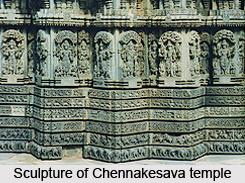

Sculpture of Chennakesava temple

There are several pillars which have been decorated with intricate sculptures. Narasimha pillar is the most popular amongst them. All the 48 pillars are unique; however the four central pillars and the ceiling they support are noteworthy. There is a possibility that these pillars have been hand chiselled while the others were lathe turned. These pillars bear madanikas (Salabhanjika-celestial damsels). They have been depicted various forms. Some of them are popular like "The lady with the parrot", "The huntress" and Bhasma mohini. Other sculptures include Sthamba buttalika which are made in the Chola style.

At the base of the outer walls are frescos of charging elephants. Above the horses are panels with floral designs, above which sculptures depict figures from the epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata.

The doorways that lead to the mandapa have on both sides an image of "Sala slaying a tiger". Sala is popularly known as the founder of the Hoysala Empire. Other sculptures here are the Narasimha image in the south western corner, Shiva-Gajasura, "Gajacharmambaradhari" on the western side, the winged Garuda, a consort of God Vishnu standing facing the temple, dancing Kali, a seated Ganeshaands several others. The sculptural style bears similarities with wall sculptures in temples of northern Karnataka and adjacent Maharashtra.

Sculpture on Exterior walls

The exterior walls of the Chennakeshava Temple are adorned with an array of sculptures, providing a visual narrative that captivates the visitor during the circumambulation of the temple over the jagati platform. These sculptures, divided into distinct horizontal bands, reveal a wealth of artistic detail and cultural significance:

Elephant Band: The lowest band features sculpted elephants, each bearing a unique expression. These elephants serve as symbolic supporters of the entire temple structure.

Empty Layer: Above the elephant band lies an unadorned layer, providing a subtle transition to the next artistic band.

Cornice Work: A cornice band, adorned with periodic lion faces, follows the empty layer, adding ornamental intricacies to the temple`s exterior.

Horsemen Band: Along the back of the temple, a row of horsemen in various riding positions is depicted, adding a dynamic element to the temple`s exterior.

Figurine Band: The fifth carved band showcases small figurines, primarily depicting females with diverse facial expressions facing the viewer. Periodically, Yakshas, facing towards the interior of the temple, are integrated into this band. Additionally, this layer features numerous dancers, musicians, and professionals with their tools.

Pilaster Band: Above the figurine band, pilasters are interspersed, with secular figures, predominantly females and couples, carved between them.

Nature and Creepers Band: Further above, a nature and creepers band envelops the temple, incorporating scenes from the Ramayana epic.

Life Scenes Band: Above the nature and creepers band, scenes from everyday life are portrayed, reflecting the principles of kama (desire), artha (wealth), and dharma (duty). These scenes encompass courtship, eroticism, family life, economic activities, and festive celebrations.

Mahabharata Band: Towards the northern outer wall, friezes depict scenes from the Mahabharata, adding an epic touch to the temple`s exterior.

Perforated Stone Windows and Screens: Above these bands, a later construction phase introduced 10 perforated stone windows and screens to both the north and south sides of the temple. These screens feature intricate Purana scenes and characters, including depictions of Hoysala court scenes, deities, legends, and mythological narratives.

Madanakai Figures: Capitals of the supporting pillars are adorned with madanakai (Salabhanjika) figures. These sculptures encompass various subjects, such as Durga, huntresses, dancers in Natya Shastra abhinaya mudra (acting postures), musicians, and individuals engaged in everyday activities.

Large Reliefs: The exterior walls also feature 80 large reliefs, including 32 of Vishnu and 9 of his avatars. Additionally, there are representations of Shiva in various forms, including Nataraja, Bhairava, Harihara, Surya, Durga, Ganesha, and others. Notable reliefs depict scenes like Arjuna winning Draupadi, Ravana lifting Mount Kailasha, and Daksha, Bali, and Sukracharya.

These sculptures on the exterior walls of the Chennakeshava Temple serve as a remarkable testament to the artistic, cultural, and religious facets of the Hoysala dynasty and the era in which the temple was constructed. They depict a rich tapestry of narratives, offering a glimpse into the diverse aspects of life and mythology that were integral to the society of that time.

Sculpture on Interior Walls

Sculpture on Interior Walls

Within the Chennakesava Temple, one encounters a remarkable array of sculptures gracing the interior walls, each contributing to the temple`s architectural and artistic splendor. The temple boasts three entrances, and flanking these doorways are elaborately adorned sculptures known as dvarapalaka, signifying doorkeepers. These sculpted guardians welcome visitors and set the tone for the artistic marvels that await inside.

The central hall of the temple, referred to as the navaranga, originally possessed an open design on all sides except the west, where the sanctum is located. Over time, each of these sides was enclosed with intricate perforated screens. While this architectural modification served certain practical purposes, it also significantly reduced the amount of natural light entering the hall, making it somewhat challenging to fully appreciate the intricate artwork without additional illumination.

The artistic journey within the temple begins at the entrances to the central hall. Each entrance leads to raised verandas on both sides, further enhancing the aesthetic experience. Within the navaranga, one encounters a stunning array of carved pillars, with a prominent domed ceiling at its center. Notably, the mandapa boasts a total of 60 "bays," or compartments, adding to its architectural grandeur.

The navaranga within the Kesava temple at Belur holds a distinctive distinction among Hoysala temples. It stands as the largest of its kind, characterized by a triratha diamond-shaped layout. This architectural feature, as noted by James Harle, adds to the unique and impressive nature of the temple`s interior design.

Sculpture on Pillars and Ceiling

The navaranga hall within the Chennakesava Temple showcases an array of remarkable sculptures adorning its pillars and ceiling, contributing to the temple`s architectural and artistic grandeur. Here are the key features of the sculptures within this sacred space:

Pillars:

The navaranga hall is graced by a total of forty-eight pillars, each crafted in a unique manner. However, there is a notable distinction between the central four pillars and the rest. The central quartet is later additions, dating back to 1381 CE during the Vijayanagara Empire era. They were incorporated to provide structural support to the temple, which had suffered damage.

The pillars come in three different sizes, with two of them garnering particular attention. One is famously known as the Narasimha pillar, renowned for its intricate carvings from top to bottom, including a miniature bull known as kadale basava. Legend has it that this pillar was once capable of rotation due to its unique support, although it no longer retains this ability.

The Mohini pillar is the other standout, featuring a female avatar of Vishnu alongside eight bands of carvings. These include representations of Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva, the ten avatars of Vishnu, the directional deities, and mythical creatures that blend the body of a lion with the faces of various wild animals. Notably, the four central pillars were meticulously hand-carved, setting them apart from the others, which were lathe-turned.

Ceiling:

The center of the navaranga hall features a sizable open square, above which extends a domed ceiling measuring approximately 10 feet in diameter and 6 feet in depth. The apex of this dome features a lotus bud adorned with intricate carvings of Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva.

The lower portion of the dome is adorned with a series of friezes depicting episodes from the Ramayana, providing a visual narrative that complements the temple`s religious significance.

Madanikas (Salabhanjika): The capitals of the four central pillars are adorned with madanikas, or Salabhanjika figures. These include a representation of Saraswati, the Hindu goddess of knowledge, arts, and music, engaged in a dance. The other figures depict dancers in various postures, each conveying distinct expressions. One is depicted arranging her hair, another is captured in a Natya posture, and the fourth holds a parrot perched on her hand. Notably, the head and neck jewelry on these figures is made of rock and is freely mounted, allowing for movement. Similarly, the bracelets on these sculptures are also moveable.

Ceiling Design: The design of the ceiling follows the principles outlined in Hindu texts, presenting a modified utksipta style with images arranged in concentric rings.

Other Reliefs: Within the hall, one encounters large images depicting Vishnu`s avatars, friezes illustrating Vedic and Puranic histories, and additional scenes from the Ramayana epic. These reliefs serve to enrich the temple`s artistic tapestry and offer a visual narrative that aligns with its religious significance.

Sculpture on Sanctum

The journey through the Chennakesava Temple`s architectural and sculptural wonders leads us to the sacred sanctum, a space of profound significance within this religious edifice. Here are the salient features of the sculptures and elements within the sanctum:

Sanctum Entrance:

Transitioning from the mandapa, visitors arrive at the threshold of the garbha griya, the sanctum sanctorum. The doorway leading to this sacred space is flanked by dvarapala, the guardian deities known as Jaya and Vijaya, who stand as sentinels symbolizing protection.

Above the doorway`s pediment, the central figure of Lakshminarayana is prominently featured, underscoring the temple`s devotion to this divine form of Vishnu.

Just below this central depiction, one encounters sculpted musicians gracefully playing musical instruments that date back to the 12th century, providing a cultural and historical glimpse into the era in which the temple was built.

Flanking the doorway are two makaras, mythical sea creatures, with Varuna and Varuni, the deities of water and oceans, riding atop them. These symbolic elements reinforce the sanctity of the entrance.

The Deity:

Inside the square sanctum, the focal point is the sacred image of Keshava, also referred to in inscriptions as "Vijayanarayana." This divine representation stands upon a pedestal elevated approximately 3 feet above the ground, commanding a sense of reverence.

The image itself stands at a height of about 6 feet and is adorned with a radiant halo. It is distinguished by its four arms, each bearing significant attributes. The upper hands grasp the chakra (discus) and shankha (conch), emblematic of Vishnu`s divinity. In the lower hands, Keshava holds a gada (mace) and a lotus, symbolizing power and purity.

The halo encircling the deity`s form is intricately adorned with cyclical carvings, representing the ten avatars of Vishnu. These avatars include Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Narasimha, Vamana, Parasurama, Rama, Krishna, Buddha, and Kalki, offering a visual portrayal of the divine manifestations.

Craftsmen behind the Sculptures at Chennakesava Temple

The Chennakesava Temple reflects the unparalleled craftsmanship of the Hoysala artists who dedicated their skills to its construction. Some of the Hoysala artists signed their work in the form of inscriptions. In doing so, they sometimes revealed details about themselves, their families, and origin.

Ruvari Mallitamma: Ruvari Mallitamma emerges as a prolific artist, revered for his exceptional talent. His legacy endures through more than 40 sculptures within the temple complex.

Dasoja and Chavana: Dasoja and his son Chavana hailed from Balligavi, situated in the modern Shimoga district. These skilled craftsmen made substantial contributions to the temple`s artistic wealth. Chavana is particularly credited with the creation of five madanikas, while Dasoja achieved the carving of four of these iconic sculptures.

Malliyanna and Nagoja: Malliyanna and Nagoja, through their craftsmanship, brought to life intricate depictions of birds and animals within the temple`s sculptures, adding a touch of natural beauty to the sacred space.

Chikkahampa and Malloja: Among the artisans whose work adorns the temple`s mantapa, Chikkahampa and Malloja stand out for their contributions. Their artistic prowess is reflected in the sculptures they crafted.