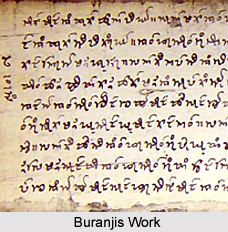

Buranjis are the historical documents that hold a place of importance in the Assamese Literature. The most important development in Assamese literature under the Ahoms is the Buranjis, the chronicles of the Ahom court.The Buranjis were compiled under royal edicts and under the decrees of the high dignitaries of the state, for they alone could grant access to State documents on which the chronicles had invariably to be based. These documents were principally the periodic reports transmitted to the court by military commanders and frontier governors, diplomatic epistles sent to and received from foreign rulers and allies, judicial and revenue papers submitted to the kings and ministers for final orders, and the day-to-day annals of the court which incorporated all the transactions done, important utterances made, and significant occurrences reported by reliable eye-witnesses. (Asam Burahji, Introduction). The Buranjis were at first written in Ahom, the language of the rulers. Later, however, they came to be compiled in the Assamese language. The Buranjis constitute an unprecedented and glorious chapter in Assamese literature. It will not be an exaggeration to remark that it is from these Buranjis that modern Assamese prose emerges.

Buranjis are the historical documents that hold a place of importance in the Assamese Literature. The most important development in Assamese literature under the Ahoms is the Buranjis, the chronicles of the Ahom court.The Buranjis were compiled under royal edicts and under the decrees of the high dignitaries of the state, for they alone could grant access to State documents on which the chronicles had invariably to be based. These documents were principally the periodic reports transmitted to the court by military commanders and frontier governors, diplomatic epistles sent to and received from foreign rulers and allies, judicial and revenue papers submitted to the kings and ministers for final orders, and the day-to-day annals of the court which incorporated all the transactions done, important utterances made, and significant occurrences reported by reliable eye-witnesses. (Asam Burahji, Introduction). The Buranjis were at first written in Ahom, the language of the rulers. Later, however, they came to be compiled in the Assamese language. The Buranjis constitute an unprecedented and glorious chapter in Assamese literature. It will not be an exaggeration to remark that it is from these Buranjis that modern Assamese prose emerges.

The historical works or Buranjis are numerous and voluminous. Knowledge of Buranjis was an indispensable qualification to an Assamese gentleman. The compilation of a Buranji was a sacred task,` and, therefore, it was customary to begin it with a salutation to the deity. The chronicles were prepared generally by men who had a comprehensive knowledge about state affairs, and we have several Buranjis whose authors were high government officials. Hence the language of these chronicles is dignified and graceful. As they are factual records, they have been put in a language which is ordinarily free from sentimental rhetoric. They are simple, easy, unpretentious, and unquestionably charming. All these vast historical writings have not yet been completely brought to light.

Date of Origin of the Buranjis

The dates of composition of all these Buranjis have not definitely been ascertained; they were perhaps compiled over a long period, beginning from the late sixteenth to the early nineteenth century. Chronologically speaking, Purani Asam-Burahji, edited by the late Pandit Hemachandra Goswami, may be taken to be the earliest: Goswami considers the work to have been compiled in the reign of Gadadhar Singha (1681-1695). Another chronicle, Svarganarayandeva Maharajar-Akhyan, now published under the title Asdm Bvrahji, also appears to have been compiled, according to Dr. S. K. Bhuyan, during this period. Pandit Goswami also came to the conclusion that Katha-Gita was composed at some time after 1594. So the time intervening between the composition of Katha-Gita and Purani-Asam Buranji is roughly about one hundred years. Purani-Asam Buranji shows clearly how during these one hundred years Assamese prose was shaping itself. It is true that Bhattadeva broke away from the conventional ornamental style, and, for the first time in the history of Assamese literature, adopted the spoken language. But he was not completely free from the influence of the ornate and cultivated Sanskritised style. As already pointed out, Bhattadeva indeed succeeded to a large extent in using an Assamese vocabulary in spite of the classical learning that encumbered him. But in the structure of his sentences he could not completely get away from the Sanskrit model, and a large percentage of Tatsama words made their inroads into his writings. The language of the Buranjis, however, is completely free from classical influence as they were written on subject-matter which was entirely different in tone and accentuation. The Buranjis have no association whatsoever with scriptural texts. They are annals of royal families and intimate portrayals of the contemporary scene, compiled by wise and experienced men of affairs imbued with the sense of historical perspective. They give us chronological accounts of the court life, the royal routine and the proceedings of the royal court.

Though there was no need for literary airs and graces, yet the Buranjis are not wholly devoid of them. In this connection another remark of Dr. S. K. Bhuyan, made with reference to the literary flavour of Padsah-Buranji, may also be applied to other Buranjis with equal force. Scattered throughout the entire Buranji literature are numerous instances of worldly wisdom and original thoughts. The secret of the literary success of the Buranjis lies to a great extent in sentence construction, local idiom and the expressive cadence of the spoken language. The writers are adepts in expressing themselves in short sentences and simple and homely phraseology. The Buranjis contributed largely towards the enrichment of Assamese vocabulary in its various ramifications in diverse fields. They incorporate a large number of administrative and legal terms current in the Ahom court. This development was due to the predominance of eastern Assam as the seat of the Ahom court and administration, and centre of trade and commerce: a fact which made eastern Assamese the language of affairs.