The Britishers were autocrats in India. They maintained their authority by force; force of arms, force of character, force of suggestion. The barons of the erstwhile princely kingdoms were kept severely in their place, beneath the sovereignty of the British Crown; though in the last years of the Empire, Indians did join the higher echelons of authority. However, to the very end the power to make the greatest decisions were still reserved for the British themselves. It is hardly surprising then that British public architecture were seldom, as it were, consultative in style. Indians were not often invited to approve their plans. They had by and large the unmistakable stamp of `take it or leave it` and were drawn as diagrams of supremacy. In the very last years of the Empire, it occurred to some designers that Indians one day might themselves occupy these halls of power, but even then they seldom progressed beyond the condescending.

The Britishers were autocrats in India. They maintained their authority by force; force of arms, force of character, force of suggestion. The barons of the erstwhile princely kingdoms were kept severely in their place, beneath the sovereignty of the British Crown; though in the last years of the Empire, Indians did join the higher echelons of authority. However, to the very end the power to make the greatest decisions were still reserved for the British themselves. It is hardly surprising then that British public architecture were seldom, as it were, consultative in style. Indians were not often invited to approve their plans. They had by and large the unmistakable stamp of `take it or leave it` and were drawn as diagrams of supremacy. In the very last years of the Empire, it occurred to some designers that Indians one day might themselves occupy these halls of power, but even then they seldom progressed beyond the condescending.

The first traces of British public architectural buildings in India were warehouses or godowns, as the Anglo-Indians called them. Forts however replaced the primary architectures as second in line to being built. This was always the case; Whether Company or Crown, happening like a militaristic regime, cap-a-pie against foreign enemies as against native subversives, loaded with uniforms, battle honours and regimental loyalties. Forts then, were everywhere in British India: story-book forts on the Khyber, island-batteries in the harbour of Bombay, ancient strongholds of Mughal or Maratha appropriated by the British for their own use. Each of the three Presidency towns (respectively being Bengal, Bombay and Madras) was centred upon a fort and for years their original settlements were enclosed within fortified walls.

British public architecture established itself at its finest perhaps through the Fort St. George in Madras. It was the oldest of them, re-designed in 1750 by an eminent military mathematician, Benjamin Robins. Fort St. George enclosed within its high walls not only administrative offices, warehouses, an arsenal, barracks and living-quarters for Governor and staff, but also brokers` offices, an exchange, a church, a theatre, auction rooms, a subscription library and a bank. Other fortress structures began in much the same way, but the original Fort William in Calcutta was largely destroyed when Sirajuddaula, Nawab of Bengal, briefly seized Calcutta from the British in 1756. As a result, the city acquired a new fortress which was to remain the greatest and most famous of the Anglo-Indian military works. Fort William was considered impregnable in its day and indeed never fell to an enemy. The Fort was entirely separate from Calcutta proper, isolated in its flatland beside the river.

As British power moved inland into India, military stations were established all over the subcontinent. However, British public architecture looked towards greener pastures, towards sequestered army stations. Instead of building fortresses within the cities they captured, the conquering generals established separate enclaves on their outskirts. They were termed `cantonments` and were generally set up five or six miles from the subjected city. A conscious gap was always deliberately maintained from the cantonments and other city areas. By the 1860s there were seventeen of these places. The cantonment was often elaborately equipped, but remained inescapably a petrified camp. Most of the buildings were variations of the standard bungalow. For officers they took the form of agreeable mess buildings surrounded by verandahs, gardens and tennis-courts, not unlike gymkhana clubs; for other ranks they were interpreted in long bleak dormitory buildings, not unlike prisons. British Indian architecture had received considerable impetus under colonial public architectural wonders, with the biggest cantonments located at Secunderabad. Secunderabad was situated in the Native State of Hyderabad, sprawled hugely over the boulder-strewn semi-desert country north of the Nizam`s capital.

British public architecture in Secunderabad reached its pinnacle with a building which looked remarkably like Windsor Castle and was indeed universally nicknamed after it. It was the military prison and beside it was the innermost redoubt of Secunderabad, an entrenched camp designed as the last bunker against native rebels. The prison was surrounded by a ditch seven feet deep, with a seven-foot rampart too, a stone revetment, a bomb-proof shelter and several artillery bastions.

Next in line under British public architecture were the barracks and barrack-blocks, like in the forts and the cantonments. It was consequently decreed (keeping in mind Indian hostilities) that a third of the British troops in India should always be stationed in the healthy hills. A new series of barracks was designed to house them. Some of these were admirable and among the best was the new military station built at Jakatalla in the Nilgiris of Madras Presidency. This was laid out on the flanks and ridges of a low cluster of hills, approximately 6000 feet above sea-level. The centre of the station was the chief barrack-block and this was extremely handsome. This particular British Indian architecture atop the Nilgiris was not like any other British barrack. On three sides of the square were first-floor entrances, approached by double flights of steps and surmounted by pediments. The whole structure, capped with elegant white lanterns and flagpoles, gave an agreeable sense of space and freshness.

British public architecture gradually gained momentum with the first substantial administrative buildings being erected by the East India Company in Madras and Calcutta. The best-known of them was the block known as Writers` Buildings in Calcutta, built in 1780 as a hostel and training-centre for young European clerks (or `writers`). It was replaced in the nineteenth century; Writers` Buildings occupied one side of the main city square, Tank Square, so called because of the reservoir in the middle of it. Architecture of Writers` Buildings was earnest with its designer being Thomas Lyon, thought to be a former carpenter. The appearance of the Buildings was severely barrack-like in form. Its nineteen sets of apartments, all identical, were contained in a very long, solid three-storey block, classical in style, with fifty-seven sets of identical windows, a flat roof and a central projection with Ionic columns.

Besides Calcutta, British Raj also had concentrated in public architectural buildings in prime places. In the more florid atmosphere of Madras, the East India Company erected a very different building for its young officials. The Old College, a masterpiece of eighteenth-century heyday, still stands grand and majestic. The College can be reached by crossing a graceful contemporary bridge over the River Cooum and passing through a white ceremonial gateway, where on the right there can be witnessed a long castellated building, similar to Gothic architectural mode.

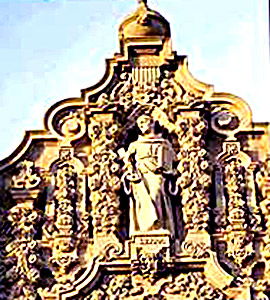

Moving forward in Victorian times, the British deemed it necessary to replace the Writers` Buildings in 1880 with a new Secretariat for the Bengal Government. By then the imperial purpose in India had greatly changed and the imperialists were not merely making money and campaigning, but improving the Natives too. The new British public architectures hence perfectly illustrated the change. The Secretariat occupied the same side of the same square, now known as Dalhousie Square, having a large statue of that Viceroy in it. If the old buildings spoke of Company earnestness, the new ones proclaimed the zeal of State. Known to have been built in the French Renaissance style, the Secretariat was replete with architectural symbolisms of one sort and another and ornamented with sculpted figures of didactic meaning. In the middle stood Minerva, goddess of presiding wisdom.

In terms of comparison, the Secretariat put up by the Victorians in Bombay, was far more intimidating in the illustrious list of British public architecture. Bombay Secretariat was one of a tremendous series of official buildings looking out over a green maidan to Back Bay and the Arabian Sea. Colonel H. St. Clair Wilkins, Royal Engineers, later aide-de-camp to Queen Victoria, was the designer of this huge structure and he took seven years to complete it. The building was massive, with a somewhat spiky tower, wrought iron verandas and wide balconies, shaded by gigantic screens of palm matting.

Zeal of another class in British public architecture was suggested by a series of three Government buildings in Shimla. These were sited rather picturesquely, lop-sided down the slopes of a steep hill, between the Gothic tower of Christ Church at the top of the ridge and the jumbled bazaar quarter below. But structurally they were very forbidding. Each Government Building was a solid square block, brutal of silhouette, surrounded by the usual open verandas, but held together visibly by iron stanchions. The nineteenth-century designers expressed, in one way or another, the exotic power and improbability of British presence in India. By twentieth century the pattern of British Indian architecture through the Government buildings (now more often entrusted to professional architects) was generally much less forceful. A mild classical style was the norm and the expression was less instructive than persuasive, even slightly reticent.

A characteristic exercise was the new Government quarter of Patna, a city which became the capital of a new province, Bihar and Orissa, in 1912. During this time, the Empire itself was beginning to lose its flair. The presiding architect was J. F. Munnings, of the Public Works Department and he laid it out spaciously but unassertively, with an engaging rather than extravagant white house for the Governor. `Extreme symmetry` was generally a symptom of this school of design under British public architecture and the Patna Secretariat was no exception. It was built in a neo-classical kind, only faintly tinctured with the Orient. The Patna Secretariat had a tall tower in the middle and exactly symmetrical wings connected to the main block by shallow bridges. On the other hand, the most celebrated administrative buildings erected by the British in twentieth-century India have been endlessly photographed, have been the subject of unceasing controversy and have entered the permanent imagery of the land. They were the two great sandstone blocks erected by Sir Herbert Baker in New Delhi (now noted and referred to as the North and South Blocks of Rashtrapati Bhavan), together with the circular Parliament House not far away. They formed the heart of the new capital city. These were buildings more conventionally Anglo-Indian than Edwin Lutyens`s unique palace up the Kingsway road (the Rashtrapati Bhavan). The Secretariat blocks (North and South Blocks) were built more in an orientalised classical style. From a distance they looked, except for their domes and towers, as if like the pleasure-pavilions of Persian emperors.

British public architecture next made their presence felt through the schools and colleges they had erected, still considered prestigious. Of all the schools the British ever made, board school or high school, village kindergarten or fashionable finishing school, none was more educational than the John Lawrence Memorial Asylum erected by the Anglo-Indians in the 1860s. The Asylum was built in memory of one of their favourite English heroes, John Lawrence of Punjab, in the Nilgiri Hills near Ootacamund (popular as Ooty). Its setting was lovely and its intentions were always benevolent.

British Government in India, after its swashbuckling beginnings, was chiefly Law and Order government. As a result, British public architecture absolutely mirrored the law and order enforcement wing in its veritable constructions. The government`s principal functions were to keep peace and enable British business to get on with its job. An elevating purpose, though, developed. In the mid-nineteenth century three universities were established and others presently followed. There were also multitudes of lesser educational institutions, some for the children of Anglo-Indians, some for aboriginals, some technical, some religious, some called colleges and some institutes. St. John`s College, Agra, which was started by the Church Missionary Society, was startling too. This was a tour de force by Swinton Jacob and was an astounding mixture of the antiquarian, the scholarly and the symbolic. Other educational concerns were militant in a different way, for several of them were run along army lines, often for the sons and daughters of British soldiers. Characteristic among these instances of British public architecture was the Bishop Cotton School in Shimla.

The greater universities established by the British in India, notably those in the Presidency towns, deliberately set out to transfer British ideas and values to the Indian middle classes, if only to create a useful client caste. The likes of Calcutta University with its chain of colossal buildings, Madras University also with its fine concentration of buildings, mostly in the so-called Indo-Saracenic style and Bombay University, one of its most admired, abused and unmistakable structures preached peak heights in British public architecture. The structure of Bombay University consisted of an oblong quadrangle, surrounded by two-storey blocks, with an open entrance flanked on one side by a library, on the other by a high-roofed Convocation Hall. The style was pure Gothic, untouched by the Hindu or the Saracenic, with ogee windows, elaborately buttressed balconies, open spiral staircases, statue niches, pinnacles and ornately decorated arcades.

Municipal pride blossomed early in British India and the Presidency towns (respectively being Bengal, Madras and Bombay) had their vociferous local patriots almost from the start. British public architecture was busy to set up municipal organisations. City councils were among the earliest institutions upon which Britons and Indians sat apparently as equals. The Town Hall, or the Municipal Building, was thus among the proudest constructions of nearly every Anglo-Indian city. Calcutta was really the archetype of them all, when the city was approaching climax of its commercial confidence. Strictly Palladian in style, the Calcutta Town Hall was very British in appearance, without verandah and arcades. Soon afterwards Bombay countered with an even more prideful Town Hall. This was the masterpiece for British public architecture, finished in 1833 in the neo-classical style, purer than the Palladian, which was then fashionable in England. British Raj never built another Town Hall like the one in Bombay, but they continued to express their civic and municipal pretensions grandly enough until the end. In Shimla, in 1887, they built a Town Hall which housed not only the municipal offices proper, but also a supper-room, a Freemasons` Hall, a library and the Gaiety Theatre, the place for amateur dramatics in Anglo-India.

British public architecture manifested its next move through the colossal constructions of legal and law buildings. In fact, nothing caught the spirit of the Victorian Empire better than the idea of legal majesty, substantiated in India in the presence of grave judges and still graver buildings. The up-country districts law courts were hardly more than huts or sheds, even tents. But the High Courts of India were very conscious of their own importance. And the architects tried to build into them the loftiest meanings of the Empire. They were of course prominently embellished with blindfold goddesses and scales; the High Courts were also habitually the largest buildings in their neighbourhoods, towering above the rest like legal maxims. The tremendous High Court of Calcutta, built in 1872 to the designs of Walter Granville, a Government architect, was decidedly the most daunting building in town. It was modelled upon the thirteenth-century Cloth Hall at Ypres in Belgium. The High Court in Bombay, erected in 1879, was designed by Colonel J. A. Fuller of the Royal Engineers. It was built in a modish mixture of Venetian Gothic and Early English styles. However, one of the most exciting of all the British buildings in India, was the High Court on the waterfront in Madras. This huge red sandstone building challenges description, so splendidly jumbled was its presence, so elaborate were its forms and so very much complex was its effects. It was designed `in the Hindu-Saracenic style`, by two Public Works Department architects. Next door to the courts stood the Law College of Madras with their myriad towers, pinnacles and domes, some brightly coloured, some decorated in stucco patterns.

There was one class of British public architectural building in which the Britons truly excelled, that being the museum. The Indians referred to a museum as a House of Wonder. Some of the collections were very fine. Architecturally they were often interesting. The Indian Museum on Chowringhee Road in Calcutta, the most important of them all, was an Italianate palace, built in 1875 around a colonnaded courtyard full of shrubs and trees. The Victoria and Albert Museum in Bombay was a French Renaissance building, ornately detailed. Behind it was stationed one of the stone elephants which had given their names to the Elephanta Caves, while in front there stood a particularly horrible but fascinating memorial tower. In Madras a whole cultural complex was dedicated for the museum, set in handsome gardens and built in varying styles: a museum proper, a technical institute, a library, a theatre and a startling art gallery and the Empress Victoria Memorial Hall. The most ambitious of them all was the Victoria Memorial in Calcutta, dedicated entirely to the history of British rule in India. The Hall was opened in 1921 as a token of gratitude to the memory of the lately-deceased Queen-Empress.

British public architecture will perhaps never be complete without mentioning the legislative chambers which, in the late years of the Raj, came into being in all the provinces of India. They were not very charming buildings, but they were the ante-rooms of liberty. Legislative Assembly chambers went up all over the country without much sign of architectural enthusiasm. In Calcutta they were unobtrusively neo-classical, tinged with the New Delhi style. In Bombay the legislative chambers were tacked on to the back of the disused Royal Alfred Sailors` Home. And in New Delhi, the home of the central legislature, the future Parliament of India, they were added to the city plan purely as an afterthought. When the new capital was devised, in 1911, nobody had thought of a Parliament. A semi-circular Council Chamber within the Viceroy`s House was the most that seemed obligatory. The reforms in 1918 altered everything and a huge new building was built by Herbert Baker in his Secretariat manner, a few hundred yards to the north-west of the palace (Rashtrapati Bhavan).