The first signature of the British Empire in India came in the form of the British East India Company. British investors staked into the so far alien landscape of the Indian subcontinent in search of prospective opportunities that would provide ample profits. What at first seemed to be a simple business transaction between two countries in course of time led to the subjugation or annexation of territories in which spices, cotton, and opium were cultivated. Many Indian associates, such as the bankers and merchants under whose supervision laid the intricate credit networks, supported this rampant British infiltration into the Indian economy.

The first signature of the British Empire in India came in the form of the British East India Company. British investors staked into the so far alien landscape of the Indian subcontinent in search of prospective opportunities that would provide ample profits. What at first seemed to be a simple business transaction between two countries in course of time led to the subjugation or annexation of territories in which spices, cotton, and opium were cultivated. Many Indian associates, such as the bankers and merchants under whose supervision laid the intricate credit networks, supported this rampant British infiltration into the Indian economy.

The British Empire would never have been able to make a mark on Indian ground had it not been for their Indian counterparts who provided connections between the rural and the urban centers. Outside threats, such as the Napoleonic Wars (1796-1815) and the Russian extension towards Afghanistan (in the 1830s), coupled with the desire for inner stability, led to the occupation of more and more territory in India. At first, political forecasters in Britain expressed some concerns over the costs and the advantages of waging wars in India, but by the 1810s, as the territorial enhancement ultimately yielded positive results, the crown in London welcomed the assimilation of new areas.

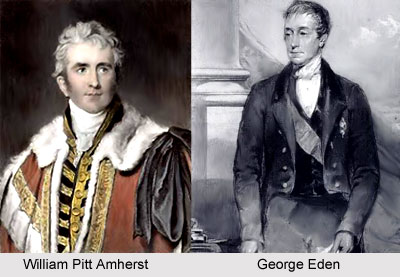

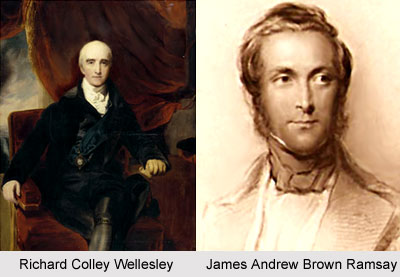

The British Empire soon stopped thinking about its own enmity with the Portuguese and the French and allowed them to settle in their maritime enclaves, which they retained even after India got her independence in 1947. The British continued to expand their territories with over brimming enthusiasm. A large number of belligerent governor-generals started persistent campaigns against several Hindu and Muslim rulers. Amongst them were Richard Colley Wellesley (1798-1805), William Pitt Amherst (1823-28), George Eden (1836-42), Edward Law (1842-44), and James Andrew Brown Ramsay (1848-56; better known as the Marquess of Dalhousie). In spite of frantic efforts by many Hindu and Muslim rulers to re-establish their power and keep away the British, many of them (like Mysore, the Maratha Confederacy and Punjab) lost their territories.

The British tremendously succeeded not only because of their supremacy in strategies and weapons but also due to their skillful diplomatic relations with Indian rulers through the "subsidiary alliance" system, introduced in the early nineteenth century. Many rulers traded away their genuine responsibilities by approving to advocate British dominion in India. In the meantime, they held on to an illusory sovereignty under the gloss of Pax Britannica.

Later on, Lord Dalhousie introduced the "doctrine of lapse" and took ready possession of the domains of the deceased princes of Satara (1848), Udaipur (1852), Jhansi (1853), Tanjore (1853), Nagpur (1854), and Oudh (1856). The Europeans, especially the British Empire increasingly began to view India`s past achievements and glory more with an eye of sweeping condemnation than with the eye of unequivocal appreciation. Instilled with an ethnocentric sense of supremacy, the British intellectuals, including Christian missionaries, headed a movement that sought to bring a large portion of the Western intellectual and technological innovations to the Indians. Many opined that Europe had taken upon itself the task of civilizing India and holding it as a trust until Indians proved themselves skilled enough for autonomous rule.

Later on, Lord Dalhousie introduced the "doctrine of lapse" and took ready possession of the domains of the deceased princes of Satara (1848), Udaipur (1852), Jhansi (1853), Tanjore (1853), Nagpur (1854), and Oudh (1856). The Europeans, especially the British Empire increasingly began to view India`s past achievements and glory more with an eye of sweeping condemnation than with the eye of unequivocal appreciation. Instilled with an ethnocentric sense of supremacy, the British intellectuals, including Christian missionaries, headed a movement that sought to bring a large portion of the Western intellectual and technological innovations to the Indians. Many opined that Europe had taken upon itself the task of civilizing India and holding it as a trust until Indians proved themselves skilled enough for autonomous rule.

The Parliament of the British Empire ratified a series of laws, among which the Regulating Act of 1773 comes first. It restrained the company traders` uninhibited commercial activities and endeavored to bring about some order in the territories under the control of the British East India Company. Restraining the company license to periods of twenty years, subject to appraisal upon renewal, the 1773 act gave the British government managerial rights over the Bengal, Bombay, and Madras presidencies. Bengal was given supremacy over the rest of the provinces because of its massive commercial vivacity. Moreover, Bengal was the seat of the British power in India (at Calcutta, now known as Kolkata), whose governor was raised to the new position of governor general. Warren Hastings was the first to hold office as the governor general (1773-85).

The India Act of 1784 is occasionally described as the "half-loaf system" because it sought to intervene between Parliament and the company directors. This act enhanced the authority of the parliament by establishing the Board of Control, whose members were elected from the cabinet. The Charter Act of 1813 acknowledged British moral liability by introducing just and humanitarian laws in India, portending future social legislative measures, and banning a number of conventional practices such as sati and thagi (or thugee, robbery coupled with ritual murder).

As governor general from 1786 to 1793, Charles Cornwallis (the Marquis of Cornwallis) made the company`s administration more professional, more bureaucratic, and more Europeanized. He also barred private trade by company employees, made a distinction between the commercial and administrative functions, and payed the company servants with generous graduated salaries. Since revenue collection became the company`s most crucial managerial function, Cornwallis made a contract with Bengali zamindars, which were regarded as the Indian counterparts to the British landed gentry. The Permanent Settlement system, also known as the zamindari system, fixed taxes for a perpetual time in return for ownership of large estates.

However, the state was debarred from agricultural expansion, which came under the rule of the zamindars. In Madras and Bombay, however, the ryotwari (peasant) settlement system was set in practice, in which peasant cultivators had to pay yearly taxes directly to the government. Neither the zamindari nor the ryotwari system proved effective in the long run because India was transformed into an international economic and pricing system over which it had no control, while the number of people relying on agriculture due to lack of other employment gradually increased. Millions of people concerned with the greatly taxed Indian textile industry also lost their markets, as they were not capable of competing profitably with cheaper textiles produced in Lancashire`s mills from Indian raw materials.

The British Empire gradually began to proliferate in India. With the establishment of the Mayor`s Court in 1727 for civil proceedings in Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras, internal justice came under the company`s jurisdiction. In 1772 an intricate judicial system, known as adalat, launched civil and criminal jurisdictions along with a composite set of codes or rules of procedure and verification. Hindu pandits as well as Muslim qazis were recruited to aid the presiding judges in deducing their customary laws, but in other cases, British common and statutory laws became applicable.

The 1850s bore testimony to the introduction of the three "engines of social improvement" that heightened the chances of the British Empire`s permanence in India. These included the railroads, the telegraph, and the uniform postal service, launched during the period in office of Dalhousie as governor general. The first railroad lines were constructed in 1850 from Howrah (Haora, across the Hughli River from Calcutta) inland to the coalfields at Raniganj, Bihar, and a distance of 240 kilometers.

In 1851 the initial electric telegraph line was placed in Bengal and soon linked Agra, Bombay, Calcutta, Lahore, Varanasi, and other cities. The three different provincial postal systems amalgamated in 1854 to aid uniform methods of communication at an all-India basis. The uniform postal rates for letters and newspapers enhanced communication between the rural and the metropolitan areas. This along with the opening of highways and waterways hastened the movement of troops, the transportation of raw materials and goods to and from the interior, and the barter of commercial information.

So the British Empire brought about major changes in India. However, the railroads did not break the social or cultural distances between various groups but inclined to create new classes in travel. Distinct compartments in the trains were set-aside specifically for the British people and also separated the educated and the prosperous from ordinary people. Interestingly, when the Sepoy Rebellion was quashed in 1858, a British official commented "the telegraph saved India." He predicted, to be precise, that the British Empire would continue to remain anchored in India. But that was not to be.