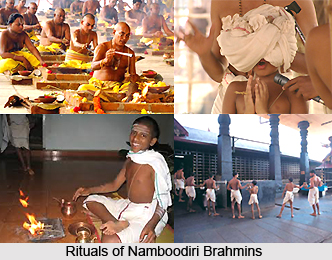

Brahmins of Kerala rose socially as well as sacerdotally until they were able to establish in the state a Hindu community more elaborately and rigidly stratified than any other in India. The teachings of Sankara probably had far less to do with this development than the long wars of the 9th century which, like all great catastrophes of their kind, shook loose the fabric of society and allowed for profound changes in the class structure and in the distribution of power. The lever that propelled the Namboodiri Brahmins of Kerala into a position of power was the development of the jenmi system of land-holding.

Brahmins of Kerala rose socially as well as sacerdotally until they were able to establish in the state a Hindu community more elaborately and rigidly stratified than any other in India. The teachings of Sankara probably had far less to do with this development than the long wars of the 9th century which, like all great catastrophes of their kind, shook loose the fabric of society and allowed for profound changes in the class structure and in the distribution of power. The lever that propelled the Namboodiri Brahmins of Kerala into a position of power was the development of the jenmi system of land-holding.

During the Chola wars the only way in which land - and the houses built upon it - could be effectively protected from the armies raiding across Kerala was for it to become sacred, in other words to become the property either of a temple or of a Brahmin joint family. The landowner would transfer his title by a transaction recorded in Tamil and written on cadjan or palm leaves; he would then revert to the position of tenant, paying his priestly landlords a share of the produce. Over the century of strife, the temples and the Brahmin families gained jenmon rights over vast areas, particularly in Malabar, until most of the cultivated land except that held by kings and local chieftains was in their hands, and many of the Nayars became tenants, sub-letting to Ezhavas or employing Pulayas as serf labourers.

At the same time as they acquired economic power through the acquiring of large areas of land, the Brahmins made use of the perils of the war to consolidate their spiritual control over the people to such an extent that they began to give threat of excommunication as a weapon even against the higher class Hindus. As conservators and preservers of holy law - and with the docile assistance of the power - they proceeded to transform the existing pattern of racial and tribal groups into a caste hierarchy so complex that even the great Swami Vivekananda from Bengal who arrived in Kerala in the end of the nineteenth century declared the state as a madhouse of castes.

The caste system formed by the Brahmins was supported by an elaborate pattern of laws intended to deepen the difference between the lower castes and the priests. Most important were the rules governing the distance at which pollution took place. A Nayar must keep a distance of sixteen feet from a Namboodiri Brahmin, Ezhava 16 feet from a Nayar and 32 feet from a Namboodiri. While a Pulaya must keep itself 32 feet away from an Ezhava, 48 feet from a Nayar and 64 feet from a Namboodiri. Atmospheric and visual pollution were peculiar to caste in Kerala. Lower-caste people were not allowed to walk on public roads, in case they polluted air, while the very sight of a Nayadi, the unfortunate beggar who represented the dregs of society, would force a Brahmin or a Nayar to undergo ritual purification.

The caste system formed by the Brahmins was supported by an elaborate pattern of laws intended to deepen the difference between the lower castes and the priests. Most important were the rules governing the distance at which pollution took place. A Nayar must keep a distance of sixteen feet from a Namboodiri Brahmin, Ezhava 16 feet from a Nayar and 32 feet from a Namboodiri. While a Pulaya must keep itself 32 feet away from an Ezhava, 48 feet from a Nayar and 64 feet from a Namboodiri. Atmospheric and visual pollution were peculiar to caste in Kerala. Lower-caste people were not allowed to walk on public roads, in case they polluted air, while the very sight of a Nayadi, the unfortunate beggar who represented the dregs of society, would force a Brahmin or a Nayar to undergo ritual purification.

The patrilineal joint family of the Namboodiri Brahmins was called the illom, and had its own peculiarities. Like the Nayars, the Namboodiri`s were anxious to safeguard their properties from division, but instead of instituting a democratic family council as the means of preventing unjustifiable fragmentation, they relied on a system of primogeniture which seems like a parody of the Freudian primal horde. Only the eldest male member of the illom was allowed to marry women of his own caste; he was allowed polygamy to the extent of four wives.

The custom of Sambandham persisted in the rural areas by the end of the nineteenth century in the state of Kerala. Sambandham was an imposition that carried its own punishment. Every child of such a union took the caste of its mother, the custom asserted the social superiority of the Namboodiris; it increased the numerical strength of the castes lower to the Namboodiris. At the same time, the fact that only the sons of one member of each illom were legitimate Brahmins meant that the strength of the priestly caste declined, not merely in relation to the increasing numbers of Nayars and Ezhavas, but even absolutely, so that during the nineteenth century, when reliable statistics were at last available, the dwindling of these lords of Parusurama`s creation became quite evident. Sambandham was certainly utilized by the Brahmins in order to consolidate their power, once achieved.

As per the Brahmins of Kerala, Parasurama ordained that Sudra women should put off chastity in order to satisfy the desires of the Brahmins is patently an attempt to justify a custom, not covered by ordinary Vedic laws, though even in this connection one should remember that Hindu legends allows extraordinary sexual liberties to holy men. Whatever their origins, the two parallel systems of inheritance and family organization, Marumakkathayam and Makkathayam, together with Sambandham, were clearly established by the time the historical record begins to become clear during the early 10th century, and they formed an important part of the structure of Hindu society by the time the first European observers arrived. The Keralite society was dominated sacerdotally by the Brahmins, militarily by the Nayars, with economic power divided between them; beside it, and at peace with it, lived other societies which accepted its political primacy but neither its customs nor its philosophy.