Bhakti Movement in Bengal had been fastened by sheer devotions of a good number of Bengali saints and social reformers who preached about the unison of God. Some of the saints of Bengal aimed to propagate the monism and dualism into a distinctly separate system.

Bhakti Movement in Bengal had been fastened by sheer devotions of a good number of Bengali saints and social reformers who preached about the unison of God. Some of the saints of Bengal aimed to propagate the monism and dualism into a distinctly separate system.

Medieval devotionalism in Bengal has different roots from that of Mahara¬shtra and developed in quite a different way. Two distinct streams of religio¬sity determined the growth of Bhakti movement in West Bengal. On the one hand there is the influence of the Vaishnava tradition, and on the other the non-Vaishnava influences from Buddhist and Hindu sources.

The Vaishnava momentum came first of all in the scene of Bhakti movement through the Bhagavata Purana with its glorification of Lord Krishna. This came to West Bengal under the Pala kings and found its typically Bengali literary trans¬formation in Jayadeva"s passionately lyrical Gita-Govinda towards the end of the twelfth century. The Gita-Govinda brings into Bengali Vaishnavism a new aspect, derived from another source than the Bhagavata, namely the prom¬inence given to Radha, the favourite of Krishna. The erotic-mystical theme of the love of Lord Krishna and Radha occupies here the centre of the stage, and henceforth dominates Bengali devotionalism.

Non-Vaishnava influence in Bhakti movement came from two sources, distinct yet interrelated. Buddhism had been on the decline in India for some time, but in Bengal it survived under the Pala Dynasty, after which it became decadent. In its de¬cadence it produced forms that affected the development of Vaishnavism, and both these Buddhist and Vaishnava forms then influenced Bengali devotional¬ism. The emphasis of them was on the female principle of the universe and they exalted the religious value of sexual passion. In reaction against the cogencies of the discipline of Mahayana Buddhism they preached the doctrine of naturalism, thus idealizing the sensuous and showing a new path to salvation in and through the senses. Intense emotionalism and eroticism pervaded their rites and mysti¬cal teachings. Chaitanya, the greatest of the Bengali Bhakti saints, did not himself come under their spell, but they certainly had an impact on the erotically in¬spired Krishna-bhakti of Bengal, leading in some cases to decadent practices.

Chandidas (fourteenth century) is the first great name in Bengali Bhakti literature. His poems, which include poems to the Mother Goddess and to Krishna and Radha, testify to his being influenced by both the Gita-Govinda and the Sahajiya doctrines. He holds that the only way to salvation is the love of God, and that this love must be based on an earthly passion for a particular person. This passion, however, needs to be sublimated, and therefore one should choose an inaccessible person, for instance a low-caste or married woman, for its object. More influential than these Sakta poems was his Krishnakirtan, devoted to the love of Krishna and Radha, permeated with great depth of feeling and transfused with profound symbolism.

Although Vidyapati (fourteenth to fifteenth century) did not write in Bengali, but in Maithili, an allied dialect, his songs on Radha and Krishna are part of Bengali Vaishnavism. He wrote eight works in Sanskrit, and nearly a thousand of his love-ballads have been collected. His work is similar in con¬tent to that of Chandidas, but his poetry is more classical, polished, and learned. In fact it mostly reads as a Maithili version of Sanskrit courtly eroticism, and the tradition injected a religious symbolism into the poems which one sometimes suspects was absent in their making.

Although Vidyapati (fourteenth to fifteenth century) did not write in Bengali, but in Maithili, an allied dialect, his songs on Radha and Krishna are part of Bengali Vaishnavism. He wrote eight works in Sanskrit, and nearly a thousand of his love-ballads have been collected. His work is similar in con¬tent to that of Chandidas, but his poetry is more classical, polished, and learned. In fact it mostly reads as a Maithili version of Sanskrit courtly eroticism, and the tradition injected a religious symbolism into the poems which one sometimes suspects was absent in their making.

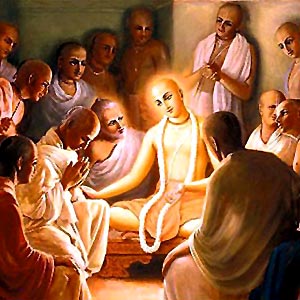

The saint who gathered together the various strands of Bengali Vaishnavism, became a reformer, and founded a sect with enormous influence on Bengal religious life was Visvambhar Misra, called Chaitanya (1485-1533). He was unique in medieval Bhakti history in that he was the initiator of a very broad movement which covered Bengal and spilled out into the whole of east India. It was a movement which encompassed an organized sect, a strong theological school, and a broad-based popular cult. Chaitanya was probably at first a member of the Sankarite Dasnami sect, and he did not leave any theological writings, but only a few devotional songs, He himself was primarily a vision¬ary ecstatic. He sent six theologians, the "six Gosvamins", to the sacred Krishnaite place Vrindavan to work out the theology of the emerging sect. These were the people who codified its doctrine and formulated its rules and rites. They were learned Sanskritists, familiar with the revelation and the tradition, and primarily intent on fitting their theology into com¬mentaries on the sacred texts, particularly the Bhagavata Purana. The main peculiarity of their theology is that Krishna is considered to be not a mere incarnation of Lord Vishnu, but the highest aspect of the divine, its "true essence". In this aspect he is united with the highest shakti, which ex¬presses the blissful power of divine life and is manifest in Radha. The aim of the devotee is gradually to ascend the ladder of bhakti till he reaches the supreme state of madhurya, or sweetness, in which he emotionally identifies himself with Radha and achieves the blissful state of union with Krishna. This step of perfection is expressed in a terminology taken over from the refined science of aesthetics, describing the experience of the beautiful. The whole theological edifice is thus based on a formalization of sublimated emo¬tional eroticism, and couched in terms derived from aesthetics. It should be stressed that this mystical theology insists strongly on virtue and on ethical training, as the necessary prerequisites for the full realization of bhakti.

In fact, this theology, elaborated at a physical distance from Bengal, in some way distanced itself from Chaitanya himself and the popular movement that grew around him. Chaitanya expressed himself in the sankirtan, a session of hymn-singing by a group of devotees. These songs were often accompanied by ecstatic dancing to the sound of tambourines. In homes or temples the sessions took place, or erupted in the streets in the form of processions. Chaitanya was the centre of the cult, and a whole literature of hymns, biographies, legends, and dramas sprang up around him. In fact Chaitanya himself became the object of popular devotion, and was considered the living Krishna, or rather the incarnation of Radha-Krishna. The Chaitanyites were no social reformers militating against the caste structure. Within the sphere of devotional practice they completely rejected all distinction of caste and thus promoted a sense of equality that penetrated deep into Bengali life. Lord Krishna and Chaitanya remained the main inspiration of high Bengali culture for three centuries. The seventeenth century produced a new crop of hymnodists, the greatest of whom was Govinda Das.

In the Bhakti movement in west Bengal, the orders of sadhus sprang up in the Chaitanya tradition, but they came strongly under the decadent influence of the Tantric orders. The Chaitanya movement had a great impact on Bengali life as a whole. It gave it a special identity which persisted even through periods of stagnancy, and provided time and again new inspiration to its religious reformers and poets namely Keshab Chandra Sen, Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, and Rabindranath Tagore.

The philosophical schools that took part in the Bhakti movement in West Bengal) had brought a reformation in the mental set up of people about their thought about God. In this movement the denunciation of caste offered up alternative for Hindus from the orthodox Brahaminical systems. Moreover, the Bhakti movement had enriched the art and culture of India and even the entire world by music, literature and art and provided India with reformed spiritual momentum.