Bansuri is an Indian musical instrument that is a simple bamboo tube. It is common in the North Indian or Hindustani classical music. It is found in many parts of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Nepal. It is an antique musical instrument of the Indian subcontinent. It is called "nadi" and "tunava" in the Rig-Veda and in other Vedic texts of Hinduism.

Bansuri is an Indian musical instrument that is a simple bamboo tube. It is common in the North Indian or Hindustani classical music. It is found in many parts of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Nepal. It is an antique musical instrument of the Indian subcontinent. It is called "nadi" and "tunava" in the Rig-Veda and in other Vedic texts of Hinduism.

Etymology of Bansuri

The word bansuri originates from the "bans" which means bamboo and "sur" meaning piece of music. In early medieval texts, the Sanskrit word "vamsi" which is derived from root "vamsa" meaning bamboo. A flute player in these medieval texts is called "vamsika".

History of Bansuri

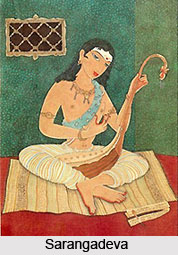

Bansuri is a simple musical instrument which can be found in many ancient cultures. According to the legends, the three birthplaces of Bansuri are Egypt, Greece and India. The early on medieval Indian bansuri was however, significant with its dimension, manner, bindings, and mounts on ends. It is discussed as a significant musical instrument in the "Natya Shastra" and is mentioned in a lot of Hindu texts on music and singing. The Bansuri is however referred to by other names such as "nadi", "tunava" in the Rig-Veda and other Vedic texts of Hinduism, or as "venu" in post-Vedic texts. The Bansuri is also mentioned in various Upanishads and Yoga texts.

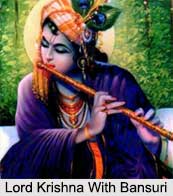

References to the Bansuri can be witnessed since the times of the Rig Veda, even in the murals of Ajanta and Ellora caves. It is basically a folk instrument, invariably linked to the lives of Lord Krishna. However, it was only during the "Bhakti movement" that Bansuri rose to prominence. During the latter part of the 19th century, the Carnatic musical geniuses took up the Bansuri as an inseparable part of a concert ensemble. Slowly, it also was infused into the North Indian musical arena, basically by the untiring efforts of Pt. Pannalal Ghosh. His innovations and improvisations are historical and can never be surpassed. The Bansuri in use today is made from bamboo, taken from the forests of Assam and North-East. Generally with six finger holes - one for blowing and the remaining for the fingers, Pt. Pannnalal Ghosh added one further hole to facilitate the playing of lower octaves.

References to the Bansuri can be witnessed since the times of the Rig Veda, even in the murals of Ajanta and Ellora caves. It is basically a folk instrument, invariably linked to the lives of Lord Krishna. However, it was only during the "Bhakti movement" that Bansuri rose to prominence. During the latter part of the 19th century, the Carnatic musical geniuses took up the Bansuri as an inseparable part of a concert ensemble. Slowly, it also was infused into the North Indian musical arena, basically by the untiring efforts of Pt. Pannalal Ghosh. His innovations and improvisations are historical and can never be surpassed. The Bansuri in use today is made from bamboo, taken from the forests of Assam and North-East. Generally with six finger holes - one for blowing and the remaining for the fingers, Pt. Pannnalal Ghosh added one further hole to facilitate the playing of lower octaves.

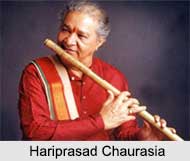

It was during the latter part of the 19th century that the flute came to occupy its esteemed place in the Carnatic repertoire as a solo instrument due to the tireless efforts of the inspired genius, Sarabha Shastri. His gifted student, Palladam Sanjeeva Rao continued his legacy and made the Bansuri a popular instrument among thousands in the south. T.R. Mahalingam, or Mali as he is popularly called, through the sheer force of innate genius and unerring instinct brought about several innovations in the style of playing and restored its lost glory in the hearts of millions in the south. In the north, however, the instrument had to wait for the magical fingers of Pannalal Ghosh to raise it to the level of a solo instrument. Later Pt. Hariprasad Chaurasia, Pt. Vijay Raghav Rao and Pt. Raghunath Seth popularized it among millions all over the world.

Significance of Bansuri

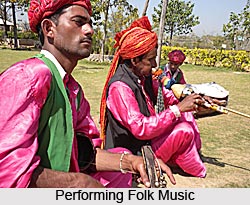

In Indian art and culture, Bansuri is inextricably interlinked with the life and loves of Lord Krishna. Musicologists hold that, along with the "veena" and the "mrridang", Bansuri or the "venu" is one of the oldest Indian musical instruments. It figures as one of the key accompanying instruments in the Rig Veda and Atharva Veda, as also the Puranas. Both celestial and human beings are shown to play it in the mural paintings in Ajanta, in the sculptures in Ellora and Sanchi. Importantly, it has been part of numerous pastoral, folk and regional ensembles from time immemorial.

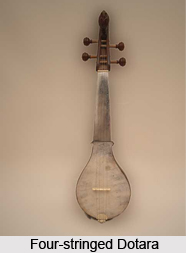

The modern day Bansuri used in Hindustani recitals is made of straight and tidy bamboo of even bore, closed at one end. The Bansuri used in Hindustani concerts is usually two-and-a-half to three feet long, possesses six finger holes and one for blowing.

Techniques of Bansuri

Techniques of Bansuri

Six fingers have to be placed in the finger holes in a varying manner to reproduce the intricacies and minutiae of "raagas". In North India, Bansuri is placed almost horizontally with the lower end slanted towards the ground. The player, who sits cross-legged on the ground, has to use blowing and fingering techniques to get the required tonal modulations. Most players follow the Pannalal model of using two other types of flutes besides the playing flute to delineate "raagas". The unusually long and stout bass Bansuri helps the player play the lower octave with great effect, while short and light flute is used for playing catchy folk and regional airs. The man playing Bansuri can generate two-and-a-half and, at times, three octaves quite easily, thus making it close companion of the human voice. Unlike the Hindustani Bansuri, the Carnatic Bansuri is shorter and possesses eight playing holes bored differently from its North Indian counterpart. The sound produced is also far more shrill compared to the mellow bass resonance given off by the Hindustani bansuri.

The Hindustani Bansuri, for the most part, follows the same format of presentation used by stringed instruments. First comes the free "alaap", which is followed by the "vilambit gat" and eventually rounded off with the "drut gat". Hariprasad Chaurasia, following the Maihar style of presentation, has introduced both the "jod" and the "jhala" used in sarod and the sitar as part of his repertoire.

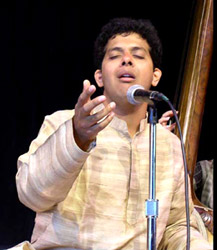

Hariprasad Chaurasia, Raghunath Seth, Rakesh Chaurasia, Nityanand Haldipur, G.S. Sachdev, Deepak Ram, Pannalal Ghosh, Shivkumar Sharma, Brijbushan Kabra are some of the famous Bansuri players from India.