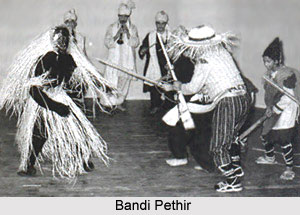

Bandi Pethir is popularly known as "clown play". A body of such farcical plays had been preserved through oral tradition. This was previously spelt as Bhand Pather that means a distinct Kashmiri performing art combining mimicry, buffoonery, music, and dance, which emerged some 2000 years ago and reached its culmination in the tenth century. The Sanskrit language esthetician Abhinavagupta, said to have lived in Kashmir, refers to it in his Abhinavabhamti in tenth century as Bhanda-Natya i.e. "down-theatre". It has remained the most popular folk form of Kashmiri theatre for the last thousand years because its scope blends several arts to entertain, inform, and persuade as well.

Bandi Pethir is popularly known as "clown play". A body of such farcical plays had been preserved through oral tradition. This was previously spelt as Bhand Pather that means a distinct Kashmiri performing art combining mimicry, buffoonery, music, and dance, which emerged some 2000 years ago and reached its culmination in the tenth century. The Sanskrit language esthetician Abhinavagupta, said to have lived in Kashmir, refers to it in his Abhinavabhamti in tenth century as Bhanda-Natya i.e. "down-theatre". It has remained the most popular folk form of Kashmiri theatre for the last thousand years because its scope blends several arts to entertain, inform, and persuade as well.

Features of Bandi Pethir

Certain features have been present in every Bandi Pethir over the centuries. Typically it starts with a musical performance, which, besides attracting spectators, creates an emotional mood, that accord with the intended drama. The three essential components of Bandi music are the oboe-like swarnai, a small one-sided stick-drum or nagari, and a big dhol. At the end of the musical prelude, called catusak, the performers sing hymns and pray for the well being of the audience. This is followed by a prologue to the Pethir, in the form of a brief conversation among the three main actors who intimate the theme and plot. The principal actors are the magun or the leader, sutardhar or the commentator, vidushak or maskhari i.e. the jester, and pariparsok or kurivol i.e. the lasher. The magun produces the play and prays for the people, the sutardhar comments on the action, the maskhari delights the spectators with his silly tricks and taunts, and the kurivol lashes the jester whenever he goes beyond control.

Modern Day Bandi Pethir

Bandi Pethir today has deviated from many of the norms of the classical Pethir known as banditsok or "bands clan", but in spite of the vicissitudes of the centuries, its rudiments have remained intact. It continues as a full-blown dramatic form in which several arts like masks, mime, music, and dance converge. Although it reflected the changing milieus, its minimal stage fixtures did not require fundamental alteration. The repertoire of available Pethirs is reminiscent of the middle ages, as far back as the eleventh century. The performers are tutored to adhere to the stories and dialogue they inherited from their ancestors.

The main reason for Bandi Pethir`s repetitious character is the absence of any parallel theatrical tradition in Kashmir, particularly since the fourteenth century. Yet it enjoyed enormous popularity in villages and towns as it expressed. On one hand, the covert protest of the suppressed populace against the forces of exploitation, and on the other hand, it reflected Kashmiris patriotic reaction to unending alien rule. The villainy of local landlords, in their spaniel loyalty to the changing foreign rulers who did not know the language and customs of the people, is the target of satire in Razipethir i.e. "Kings Play". Similarly, in Derzi Pethir reducing them to brainless fools and jesting about their haughtiness expose i.e. "Dards" Play, the hardhearted arrogance of the Dard kings. Even common men and classes living a miserable life, like the scavengers, are ridiculed for their incongruities. If in Vatal pethir scavengers are lacerated for their filthiness, in Gwaseny Pethir i.e. "Sadhus" Play`, cloistered hermits are lampooned for their incontinence and hypocrisy. These well-liked plays were performed faithfully by strolling professionals called Bhagats or Bands through the centuries. At some permanent settlements of Bands in Kashmir, they persevered to defend the legacy of Pethir from unfriendly conditions. The most important centres of these entertainers are Akingam, Takiya Imam Sahib, Wahthor, Drwagimul, Bwamay, Balapur, Pakharpur, Swayibug, Palhalan, Lolapur, Gulgam, and Kerihom. Each adheres to the style of performance established by its legendary founders, and allegiance to tradition forms the basis of distinction of the group. Some names of antiquarian interest in the field are Guly Muhar, Swadi Muhar, Madhav Muhar, Karim Shala, Mwakhti Long, Subhan Khend or Akingam, Sidiq Joo or Shangas, Razaq Wony or Imam Sahib, Karam Baland or Wahthor, and Usman Batt or Lolapur. The genre persisted despite unfavourable political climate and devastating calamity. Most of the Bands died in the famine of 1877, as witnessed by Walter Lawrence.

Post-Independence Phase of Bandi Pethir

Soon after 1947, when politics needed an effective and direct rapport with the masses, there was a sudden revival of Bandi Pethir. Political and economic programmes found expression in various Pethirs which, besides providing pure entertainment to the people, disseminated the messages of family welfare, universal education, adult literacy, flood control, modernized agriculture, and so on. The state government instituted awards, organized festivals, built town halls, and established the Jammu and Kashmir Academy of Art, Culture and Languages in 1958, considerably encouraging folk theatre.

Mohammad Subhan Bhagat and Moti Lal Kemmu played the most significant roles in revivifying the flagging tradition. They not only wrote about the theory of Bandi Pethir, but also composed new Pethirs with contemporary features. Inspired by Subhan Bhagat`s work, the time-honoured centres of Bandi Pethir reorganized themselves under new groups like the Kashmir Bhagat Theatre, Kashmir Bandi Theatre, National Bandi Theatre, Alamdar Theatre, Baba Rishi Folk Theatre, Gulmarg Folk Theatre, and Shah Wali Luki Pethir Centre.