Art and architecture of Delhi Sultanate was the period when the Delhi Sultanate flourished in India. This period brought with it new styles of architecture and art to India which were quickly absorbed into the set up present previously. There are reasons for events to move in this direction. The new ideas and the existing Indian styles had several common features, thus enabling them to become accustomed to one another. Both mosque and temple possess large open courtyards and several other temples were converted into mosques by some of the foreign invaders, which formed a mixture of both Indian and foreign styles.

Art and architecture of Delhi Sultanate was the period when the Delhi Sultanate flourished in India. This period brought with it new styles of architecture and art to India which were quickly absorbed into the set up present previously. There are reasons for events to move in this direction. The new ideas and the existing Indian styles had several common features, thus enabling them to become accustomed to one another. Both mosque and temple possess large open courtyards and several other temples were converted into mosques by some of the foreign invaders, which formed a mixture of both Indian and foreign styles.

The Delhi Sultanate brought two new architectural ideas, the pointed arch and the dome. The dome forms the major decorative component in Islamic buildings, and soon the same was introduced in several other structures. The true or pointed arch used during this period, was totally dissimilar to that of the arches which were being constructed within the country before. The primitive Indian style of making arches was to first construct two pillars and then the same would be cut at interval to hold `plug in` projections. There would also be a series of squares which would step by step decrease in size forming an arch. The new artisans brought in the true arch. This was accomplished by forming the middle stone a key stone and to other stones allocates the load to the two pillars.

The idea of the dome was also newly introduced. This was slowly perfected and one of the striking examples is the dome of the famous Taj Mahal in Agra. The dome at first started out in the form of a conical dome in the Mehrauli region in Delhi and finally developed the final bulbous onion shape on the Taj Mahal. The dome effect was attained by an interesting process. At first, a square base was constructed and then at changing angles more squares adds up to the base. It thus creates a rough dome effect which was plastered in order to form it fully round and after that the squares were removed. Concrete was also used abundantly by opening up new opportunity. Concrete helped the builders to construct larger and massive structures stretching over a vast area. The local craftsmen of India were soon given training on Persian styles of art which they utilized to decorate the structures.  The artisans also at times put in some of their own ideas, and soon the Hindu traditional motifs like the lotus were introduced into the Islamic buildings. Several other instances like the Islamic buildings utilized more advanced pointed arch, they also adapted for the purpose of decoration a variant of the Hindu arch.

The artisans also at times put in some of their own ideas, and soon the Hindu traditional motifs like the lotus were introduced into the Islamic buildings. Several other instances like the Islamic buildings utilized more advanced pointed arch, they also adapted for the purpose of decoration a variant of the Hindu arch.

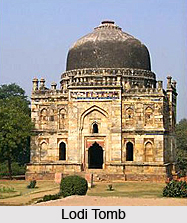

The early period of the Sultanate, namely the Slave dynasty in India and the Khiliji dynasty formed a number of exquisitely designed structures, with delicate works of art adorning them. In the Tughlaq period, the temper was less decorative and more austere and simple. This is assigned in part to the Tughlaqs` religious ideas and the depleted state finances. The Lodis and the Sayyids who came after the Tughlaqs brought the more lavish styles with the Lodis bringing in the new concept of double dome. A new decorative style was also introduced by them, mainly borrowed from Persia, enameled tiles, with grey sandstone. Terra-cotta decorative work remained popular in the period.

The period was marked with great experimentation, and a majority of the artists and engineers in India were eager to learn from the flood of new ideas entering the country at that time. The indigenous technique was retained by them and at the same time they also absorbed several new thoughts coming in their way. Thus, two different ideas mixed to form a coherent whole.

Under the Delhi Sultanate major developments were made in music as Indian and Arab forms mixed with the traditions of Persia and Central Asia. This syncretism led to the formation of a new type of music in north India quite dissimilar to that of the traditional Indian music, which retained its hold in the south. Much of the credit for this synthesis can be attributed to Amir Khusrau, the poet whose fame gave prestige to the new music, and also to the interest of the Chishti Sufis. At the independent court of Jaipur, music received special attention. At Jaunpur the last Sharqi king, Sultan Husain, was considered to be the founder of the Khiyal or romantic school of music, which went on to blossom under the Mughals. At Gwalior under Raja Man Singh the chief musician was a Muslim who systematized Indian music in the light of the changes it had undergone since the advent of the Muslims.

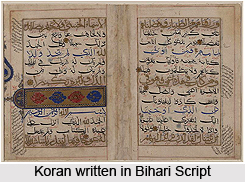

Little is known about in the field of education and the detailed curriculum of the madrasas, but it appears that medicine was accorded high importance. The earliest surviving work, written in the year 1329, by Zia Muhammad, Mazmua-i-ziai, is based on Arabic and Indian sources, and gives local equivalents of Arab medicines. Others followed with combinations of Arab, Greek and Indian works, bringing together the medical knowledge of three cultures. Very few literary works have survived from the period of the Sultanate. With the exception of a number of major pieces by poets like Amir Khusrau or Hasan, the only enduring works were those included in general histories, like the poems of Sangreza, the first poet of eminence born in India, or Ruhani`s poem of the conquest of Ranthambhor by Iltutmish.

Little is known about in the field of education and the detailed curriculum of the madrasas, but it appears that medicine was accorded high importance. The earliest surviving work, written in the year 1329, by Zia Muhammad, Mazmua-i-ziai, is based on Arabic and Indian sources, and gives local equivalents of Arab medicines. Others followed with combinations of Arab, Greek and Indian works, bringing together the medical knowledge of three cultures. Very few literary works have survived from the period of the Sultanate. With the exception of a number of major pieces by poets like Amir Khusrau or Hasan, the only enduring works were those included in general histories, like the poems of Sangreza, the first poet of eminence born in India, or Ruhani`s poem of the conquest of Ranthambhor by Iltutmish.

Perhaps the most important literary contribution during the Delhi Sultanate was in the field of history. Ancient Indian culture produced no historical literature, so surviving Muslim works are vital primary sources. These works are richly varied. While many glorify or exaggerate the role of their royal patrons, the basic historical facts are sound. The historian Baruni is particularly notable for his fascinating insights into the political philosophies of different monarchs and for his portrayal of individual personalities.

With the collapse of the power of the Sultanate in the 15th century, the rise of the provincial kingdoms fostered the growth of regional languages. While Hindu rulers had patronized Sanskrit language as the language of religion and the Epics, Muslim rulers supported the common languages of the people. Ironically, it was the Muslims who were responsible for the first translations of the Sanskrit Epics into the provincial languages.