Architecture under the nawabs of Awadh in the splendid domain of Indian architectural masterpiece can demand full attention, which was verily brought out by the crumbling and downfall of the Mughal Empire. As the Mughal Empire weakened thus, the nawabs of Murshidabad, Awadh and Hyderabad began to establish their own successor states. The architecture sponsored by the rulers and inhabitants of these new domains was heavily dependent on the Mughal style established during Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb, yet in each case new formal interpretations and meaning gave way to older forms. The results were often highly creative expressions, reflecting these houses` political faithfulness and religious attachment and expression. Architecture under the Nawabs of Awadh was quite an apprehended mission, with the smaller stately union endeavouring to make their mark coming out from the gargantuan shadow of the Mughal Dynasty. And Indian architectural genius or the opposite under the nawabs of Awadh strictly comes under the princely states category, which had established their supremacy and stronghold amidst such scenario of dilapidation.

Architecture under the nawabs of Awadh in the splendid domain of Indian architectural masterpiece can demand full attention, which was verily brought out by the crumbling and downfall of the Mughal Empire. As the Mughal Empire weakened thus, the nawabs of Murshidabad, Awadh and Hyderabad began to establish their own successor states. The architecture sponsored by the rulers and inhabitants of these new domains was heavily dependent on the Mughal style established during Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb, yet in each case new formal interpretations and meaning gave way to older forms. The results were often highly creative expressions, reflecting these houses` political faithfulness and religious attachment and expression. Architecture under the Nawabs of Awadh was quite an apprehended mission, with the smaller stately union endeavouring to make their mark coming out from the gargantuan shadow of the Mughal Dynasty. And Indian architectural genius or the opposite under the nawabs of Awadh strictly comes under the princely states category, which had established their supremacy and stronghold amidst such scenario of dilapidation.

Architecture under the nawabs of Awadh, as denoting much significance in the domain of medieval to modern Indian architecture, were not only confined in Oudh (as Awadh is also popularly acknowledged) itself, but indeed had endeavoured to spread its wings onto nearby places. During the initial period of the nawabs` power, buildings were modelled closely on Mughal prototypes, for Delhi, still the centre of courtly Muslim culture, had remained the ideal to emulate. This is evident in buildings of the central market place (chowk), commenced approximately in 1765 by Shuja ud-Daula. He had provided this chowk with an elaborate triple-arched entrance. In the market, Hasan Reza Khan, later to be one of the chief ministers of Awadh, had erected a mosque, acknowledged today as the Chowk mosque. The three bulbous domes and two minarets of this single-aisled three-bayed mosque, positioned upon a high plinth, truly dominate the Oudh skyline. This emphasis on the building`s height recalls Mughal buildings of Aurangzeb`s reign. Other aspects, however, relate to more contemporary architecture of Delhi, for example, the stucco work above the cusped arches and the ornate treatment of the mosque`s parapet.

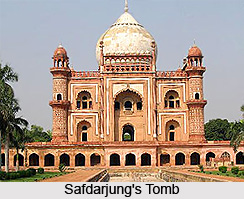

Tombs in Faizabad also were inspired by Mughal models; particularly the tomb for Shuja ud-Daula, built approximately in 1775, and one for his wife, Bahu Begum, constructed approximately forty years later, after her death in 1816, display Mughal features. Both of these tombs, like the tomb of Safdar Jang, Shuja ud-Daula`s predecessor, possess bulbous domes and are set in char baghs, the most striking and praiseworthy of architectural format that was established by the man Babur himself. The ornament on these tombs, like that on the Chowk mosque, is deeply rooted in earlier Mughal traditions, a simple reiteration which was time and again noticed in the architecture of Awadh under the nawabs. At the same time, these tombs reveal original characteristics such as multiple entrances on the facade and elaborate parapets on the roof, significant features in the developing independent Awadhi style of architecture under reign of Nawabi India. Indeed, when stating about an India under the strict ruling of Islam, beginning with the Delhi Sultanate and ending in the nawabs and nizams, before the British had taken control, architecturally the country was at its most helm, with every kind of devise and tool being applied to take this Oriental country to great heights. As a result, though not as much over-the-top or most extraordinaire as the Mughals were, architecture under the nawabs of Awadh did try to assay a definitive path in places as far-off from Delhi or Agra.

Tombs in Faizabad also were inspired by Mughal models; particularly the tomb for Shuja ud-Daula, built approximately in 1775, and one for his wife, Bahu Begum, constructed approximately forty years later, after her death in 1816, display Mughal features. Both of these tombs, like the tomb of Safdar Jang, Shuja ud-Daula`s predecessor, possess bulbous domes and are set in char baghs, the most striking and praiseworthy of architectural format that was established by the man Babur himself. The ornament on these tombs, like that on the Chowk mosque, is deeply rooted in earlier Mughal traditions, a simple reiteration which was time and again noticed in the architecture of Awadh under the nawabs. At the same time, these tombs reveal original characteristics such as multiple entrances on the facade and elaborate parapets on the roof, significant features in the developing independent Awadhi style of architecture under reign of Nawabi India. Indeed, when stating about an India under the strict ruling of Islam, beginning with the Delhi Sultanate and ending in the nawabs and nizams, before the British had taken control, architecturally the country was at its most helm, with every kind of devise and tool being applied to take this Oriental country to great heights. As a result, though not as much over-the-top or most extraordinaire as the Mughals were, architecture under the nawabs of Awadh did try to assay a definitive path in places as far-off from Delhi or Agra.

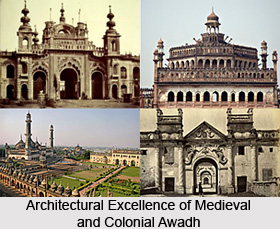

Asaf ud-Daula, Shuja ud-Daula`s son and successor, had moved his residence to Lucknow, in part to distance himself from the authoritative Bahu Begum. From the time of Asaf ud-Daula onwards, that is from 1775 to the abolition of the house of Awadh by the British in 1856, Lucknow had remained the seat of the nawabs; indeed it was from Lucknow itself that the stronghold of architectural competence was achieved - the most shining work of art under the domain of architecture under the nawabs of Awadh. Although construction was considerable under the nawabs of Awadh, architecture in Lucknow can be placed generally into two broad categories. Those structures built by the nawabs commencing approximately during the later eighteenth century for their own residences or as public works often reflect considerable European influence, while religious structures were usually based upon the architecture of earlier Indo-Islamic houses.

Apart from bridges, whose components were actually ordered from Europe and then assembled in Lucknow, it is the `palace architecture` that bears the most noticeable European characteristics. The climaxing of 18th century and the beginning and middle of 19th century was the most crucial period in India history, which was to witness the forever culmination of any kind of Orientalism under Asian rulers and was to enter into a complete British phase under the East India Company and later, the Crown. As such, after the departure of the Mughals, the `Indianisation` of India was to suffer heavy blows, mostly in the domain of architecture. As such, architecture in India under the nawabs of Awadh was wholly to be influenced by British and European influence. Features like Paladian-style columns, triangular pediments and Adam-style fanlights were all widely utilised in Lucknow`s residential architecture under and during the nawabs and a nawabi India. Even structures such as a zenana, whose purpose precluded numerous tall windows on the facade as favoured by contemporary Europeans, reflected a subtle awareness of European styles. Instead of windows, the architects provided niches with statues or fresco paintings of men. Such ornamentation and enhancement, however, were only a superficial adaptation of European tradition, for the buildings` interiors continued to follow traditional plans essential to indigenous modes of living. The European features suggest the nawabs` superficial display of regard for the British, yet at the same time uneasiness with both British dominance and British artistic styles.

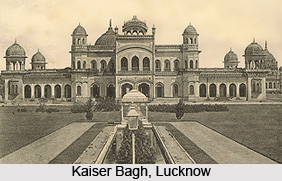

With the gradual advancement of time, India was thoroughly accustomed to the structural framework of `nawabs`, with which the architecture also had traced a few more steps. Indeed, architecture under the nawabs of Awadh, based in the north Indian portions of Lucknow primarily, was one that stood out in Islamic architectural styles in India. A series of palaces were constructed in Lucknow, from Asaf ud-Daula`s defensively viable Macchi Bhavan, built approximately in 1774, to the historic Kaiser Bagh, built approximately about 1848 by the last king of Awadh, Wajid Ali Shah. In present times, only isolated structures that once were part of the extravagant palatial Kaiser Bagh complex remain. Highly influenced and charmed by European art, the fine ornate stucco work in the shape of fish (the nawabs` royal emblem) and the floral motifs standing out along exaggerated cusped arches - are quite characteristic of the Kaiser Bagh buildings. While the well-fortified Macchi Bhavan was a symbol of the Nawabs` supremacy and command, the pleasure-garden character of the last palace, the Kaiser Bagh, reflected the impotent nature of the politically waning and declining nawabs.

Indian architecture under and during the nawabs in Lucknow and elsewhere were successful also to look towards religious construction. As such, the nawabs of Awadh and their architects seem to have felt greater ease in constructing religious structures, even though they were often part of the palace grounds. In 1784, Nawab Asaf ud-Daula had commenced an enormous Imambara, a hall used during the Shia celebrations of Muharram and for storing movable shrines (taziya) employed in these ceremonies. This complex adjoined the Macchi Bhavan Palace. It was erected to provide work and income for citizens who were suffering from a serious famine. The nawab himself had participated in the construction process as an act of religious merit, thereby, encouraging even the high-born to labour. The compound of the Imambara (now acknowledged as the legendary Bara Imambara in Lucknow) consisted of the huge Imambara, a large free-standing mosque, a step-well and elaborates entrance gates. Even in these gates the complex`s vast scale is emphasised and stressed. Nowhere is this better expressed than in the legendary and colossal Rumi Darwaza, the gate serving as the west entrance to the Imambara. This enormous gate`s high rounded pishtaq is enveloped by a series of projecting green glazed ceramic finials from which water is known to have spouted once. Typical of the Awadh nawabs` architecture, the gateway was highly creative, characterised by a sense of dynamic articulation never expressed in the more orderly structures of the Mughals.

The Bara Imambara was during the time of its construction a technological achievement, for it possessed the largest vaulted hall that ever swept an uninterrupted space. Yet other aspects of Asaf ud-Daula`s Imambara belong to an expression of standard ornament found on mosques and madrasas throughout north India.

For instance, it is adorned with magnificently rendered high stucco relief, numerous arches edged with deep cusping and crowned by a parapet of bulbous domes. While these features, seen on many of Lucknow`s religious buildings, are arranged in a manner unique to Awadhi architecture, they are all established forms utilised earlier on Mughal and other Islamic edifices. Thus in the architecture of Lucknow, just as in the other well-established Muslim house of north India - Murshidabad, long-standing Islamic forms had served as the basis of religious structures, while European sources stood behind administrative and residential structures. And herein lies that very subtle, yet definitive, differences in architecture under the nawabs of Awadh, with religion and administration dividing themselves into two distinct lines. European forms were meticulously avoided for religious architecture. Rather, the models for religious buildings were structures that had been erected by earlier Indo-Islamic houses. These models were, however, associated not with a dynasty but with the very essence of Islam.

For instance, it is adorned with magnificently rendered high stucco relief, numerous arches edged with deep cusping and crowned by a parapet of bulbous domes. While these features, seen on many of Lucknow`s religious buildings, are arranged in a manner unique to Awadhi architecture, they are all established forms utilised earlier on Mughal and other Islamic edifices. Thus in the architecture of Lucknow, just as in the other well-established Muslim house of north India - Murshidabad, long-standing Islamic forms had served as the basis of religious structures, while European sources stood behind administrative and residential structures. And herein lies that very subtle, yet definitive, differences in architecture under the nawabs of Awadh, with religion and administration dividing themselves into two distinct lines. European forms were meticulously avoided for religious architecture. Rather, the models for religious buildings were structures that had been erected by earlier Indo-Islamic houses. These models were, however, associated not with a dynasty but with the very essence of Islam.