Introduction

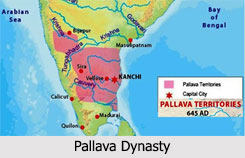

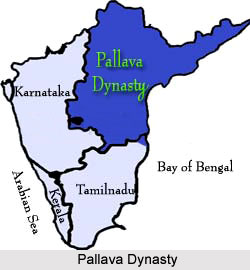

Pallava Dynasty was a famous power in South India that existed between the 3rd and 9th Centuries. They ruled northern parts of Tamil Nadu, parts of Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana with Kanchipuram as their capital. The Pallavas supported Buddhism, Jainism, and the Brahminical faith and were patrons of music, painting and literature. Mahendravarman I was a great patron of art and architecture and is known for introducing a new style to Dravidian architecture.

Pallava Dynasty was a famous power in South India that existed between the 3rd and 9th Centuries. They ruled northern parts of Tamil Nadu, parts of Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana with Kanchipuram as their capital. The Pallavas supported Buddhism, Jainism, and the Brahminical faith and were patrons of music, painting and literature. Mahendravarman I was a great patron of art and architecture and is known for introducing a new style to Dravidian architecture.

Origin of Pallava Dynasty

The word Pallava meaning branch or twig in Sanskrit is delivered as Tondaiyar in Tamil language. The Pallava kings at numerous places are termed as Tondamans or Tondaiyarkon. The word Tondan in Tamil means slave, servant, adherent or assistant and can either be suggestive of the subordinate position the Pallavas bore to the Satavahanas or reflect a dominant position pallavas enjoyed at the time of satvahanas. On disintegration of the Satvahana authority, the Pallavas avowed themselves and invaded a large part of Chola province but the soubriquet Tondon stayed and their region also came to be known as Tondamandlam. The word Pallava is a translation of Tamil word Tondaiyar and Tondaman and this discovers corroboration in various copper plate charters that bring in `tender twigs` (pallavams) of some kind in association with the eponymous name Pallava`.

The word Pallava meaning branch or twig in Sanskrit is delivered as Tondaiyar in Tamil language. The Pallava kings at numerous places are termed as Tondamans or Tondaiyarkon. The word Tondan in Tamil means slave, servant, adherent or assistant and can either be suggestive of the subordinate position the Pallavas bore to the Satavahanas or reflect a dominant position pallavas enjoyed at the time of satvahanas. On disintegration of the Satvahana authority, the Pallavas avowed themselves and invaded a large part of Chola province but the soubriquet Tondon stayed and their region also came to be known as Tondamandlam. The word Pallava is a translation of Tamil word Tondaiyar and Tondaman and this discovers corroboration in various copper plate charters that bring in `tender twigs` (pallavams) of some kind in association with the eponymous name Pallava`.

But scholars rebuff this view since it is a later usage of the term and consequently cannot be confirmed to have given rise to the family name Pallava. Some feel that the Pallavas are connected with primordial Pulindas, who were the same as the Kurumbas of Tondamandlam. Tondamandlam was a province under Maurya Emperor Ashoka in third century BCE and was later detained by the Satavahanas and thus Tondamandlam became a feudatory to the Satavahanas After collapse of Satavahanas in about 225 AD, the Pallavas of Tondamandlam became autonomous and prolonged to the Krishna River.

There have been several conjectures concerning the origin of the Pallavas. There are certain claims based on historical, anthropological, and linguistic proof signifying that the Pallavas were related to the Pahlavas of Iran. It is probable that a wave of Pahlava/Kambhoja tribes of Indo-Iranian descent migrated Southward and first settled in Krishna river valley of present day coastal Andhra Pradesh. This province is termed Palnadu or Pallavanadu. Pallavas later unmitigated their swing up to Northern Tamil province and established a prosperous realm.

Some scholars think that the Pahlavas migrated from Persia to India and established the Pallava dynasty of Kanchi, whereas, some say that they were immigrants from north, or from Konkan, Tenugu and Anarta into Deccan. They came into south India through Kuntala or Vanvasa. It is also worth remarking that the close connections of the Sakas (Scythians), the Kambojas and the Pallavas have been highlighted in numerous ancient Sanskrit texts like Mahabharata, Valmiki Ramayana, and the Puranas. In the Puranic literature, the Sakas, Kambojas Yavanas, Pahlavas and Paradas have been distinguished as united tribes, which were situated in the Scythian belt in Central Asia and were hence followers of common culture and social customs. There are other opinions supporting their indigenous origins state that they were hereditary feudatory rulers under the Vakatakas.

Combats of Pallava Dynasty

Throughout their supremacy they were in steady conflict with both Chalukya Dynasty in the north and the Tamil kingdoms of Chola and Pandyas in the south. The Pallavas were occupied in continuous combat with the Chalukyas of Badami and lastly concealed by the Chola kings in the 8th century CE. The Pallavas captured Kanchi from the Cholas as recorded in the Velurpalaiyam Plates.

Architecture of Pallava Dynasty

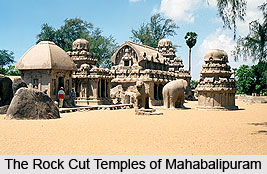

Architecture under Pallava dynasty is significant because it demonstrates the later development of the Dravidian style of architecture. The architecture of the Pallavas is classified into two periods. The earliest architecture of the Pallavas are the rock cut temples which dates back to 610-690A.D under the reign of the Mamalla rulers and the architecture of the structural temples dates back to 690-900A.D and these flourished under the Rajasimha Empire. The temples were mostly dedicated to Lord Shiva.

Architecture under Pallava dynasty is significant because it demonstrates the later development of the Dravidian style of architecture. The architecture of the Pallavas is classified into two periods. The earliest architecture of the Pallavas are the rock cut temples which dates back to 610-690A.D under the reign of the Mamalla rulers and the architecture of the structural temples dates back to 690-900A.D and these flourished under the Rajasimha Empire. The temples were mostly dedicated to Lord Shiva.

The rock cut temples of Mahabalipuram are the most magnificent features of Pallava architecture. It was built under the patronage of king Narasimhavarman I of the Mamalla period and thus it is also referred to as Mamallapuram. The first phase of the Pallava architecture is influenced by the Buddhist monasteries and chaitya halls. The principal architectural monuments of this period consist of some temples that are free standing sculptural replicas of contemporary structural temples or raths carved from the granolithic outcrops on the shore. These monuments are of the great importance for the later development of Dravid¬ian architecture because they reveal the depen¬dence of the later Hindu style on pre-existing types of Buddhist architecture. Especially re¬vealing for this latter aspect of the style is the Dharmaraja rath which has a square ground-storey with open verandahs that forms the base of the terraced pyramidal sikhara above. It has been rightly suggested that this typical Dravidian form is an adaptation of a Buddhist vihara, in which successive storeys were added for the accommodation of the monks. The terminal member of the structure is a bulbous sikhara, which is repeated in smaller scale on each of the lower levels of the terraced super¬structure. Perhaps the most distinctive feature of this and the other raths at Mahabalipuram lies in the open verandahs on the ground-storey. The pillars are of a distinctive Pallava type with the shafts of the columns supported by the bodies of seated lions.

The Sahadeva"s rath, which is classified as the Vesara temple, represents a different type of architecture. The building is of a longitudinal type with a barrel roof. This mausoleum, terminating in the semi-dome of an apse and with the chaitya motif at its opposite end, is very clearly a survival of the Buddhist chaitya-hall that had persisted in such structural temples as the Gupta example at Chezarla and to a modified extent in the Durga temple at Aihole. The Bhima"s rath has a simple barrel roof with cross section and a chaitya arch on either side. It is crowned by a row of stupikas. Another distinguishing feature of the Pallava style of architecture is perceived in the Gavaksha motif of chaitya arches framing busts of deities that crown the entablature. This architectural feature is typical of the Dravidian style.

The Sahadeva"s rath, which is classified as the Vesara temple, represents a different type of architecture. The building is of a longitudinal type with a barrel roof. This mausoleum, terminating in the semi-dome of an apse and with the chaitya motif at its opposite end, is very clearly a survival of the Buddhist chaitya-hall that had persisted in such structural temples as the Gupta example at Chezarla and to a modified extent in the Durga temple at Aihole. The Bhima"s rath has a simple barrel roof with cross section and a chaitya arch on either side. It is crowned by a row of stupikas. Another distinguishing feature of the Pallava style of architecture is perceived in the Gavaksha motif of chaitya arches framing busts of deities that crown the entablature. This architectural feature is typical of the Dravidian style.

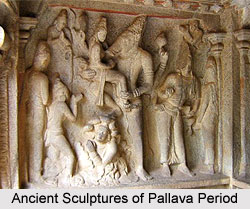

One of the raths of Mahabalipuram consists of a one-storey square cell surmounted by an overhanging, curvilinear roof, suggestive in its shape of the modern Bengali huts. This feature is an imitation of a proto¬type constructed of bamboo and thatch. The resemblance to the sikhara suggests that this most characteristically Dravidian element may also have had its origin in the form of a bamboo hut. The plastic embellishment of the raths consists of images of Hindu deities set in position on the exterior of the shrine, and also of panels exemplifying legends of Hindu myth¬ology ornamenting the interior of the sanctu¬aries. The figures appear to be a development from the style of the Later Andhra Period. The architecture retains the extremely refined attenuation of the forms at Amaravati, and is animated by the same feeling for movement and emotionally communicative poses and gesticulation. A new standard of propor¬tion is prominent in the heart-shaped faces with high cheekbones and the almost tubular overstatement of the thinness of the arms and legs. In the reliefs decorating the raths the forms are not so completely disengaged from the background as in the Andhra Period, but seem to be emerging from the medium of the stone.

The greatest architectural achievement of the Pallava artisans is the carving of an enormous granite boulder on the seashore with a representation of the Descent of the Ganges from the Himalayas. The scores of figures of men and animals, including those of the family of elephants, are represented in life size. The subject of the relief is that of all creatures great and small, the Gods in the skies, the holy men on the banks of the life giving flood, the nagas in its waves, and the members of the animal kingdom, one and all giving thanks to Lord Shiva for his astounding gift to the Indian world. The fissure in the centre of the giant boulder was at one time an actual channel for water, simulating the Descent of the Ganges from a basin at the top of a rock. In the relief at Mahabalipuram the shapes of the Gods moving like clouds across the top of the work of art, have the graceful, disembodied sophistication of the art of Amaravati. This gigantic, densely populated composition flows unrestrained over the entire available surface of the boulder from which it is carved.

The hallmark of Pallava architecture is also witnessed in the free-standing group of a monkey family in front of the tank below the great relief of the Descent of the Ganges. The understanding of the essential nature of the ani¬mals and the plastic realisation of their necessary form could barely be improved upon. This piece of architecture is the very personification of the principle mentioned in relation to the Indian canons of painting. The shapes, although only partially adumbrated, connote the finished form and pro¬claim the nature of the glyptic material from which they are hewn. In the panel of a cave in Mahabalipuram there is a relief which illustrates Durga fighting the demon buffalo, Mahisha. This episode is adapted from the Puranic legends. Goddess Durga is seated on a lion in this marvelous example of the Pallava style at its finest. She is eight-armed, and holds the weapons such as the bow, discus, and trident lent her by Lord Shiva and Lord Vishnu for the epic struggle. Her ornaments include a lofty head-dress, necklaces, jeweled belt; and her arms are covered with bracelets. This figure, like all Pallava architecture, belongs to the earliest and at the same time classic phase of Dravidian art. The whole conception is invested with a peculiarly dynamic quality that is always characteristic of Dravidian Hindu art.

After the death of the Pallava monarch Narasimha in 674 A.D. there was an end to the construction of raths and other sculptural work of Mahabalipuram. His successor Rajasimha was dedicated in the creation of structural buildings. The Pallava architecture experiences the transition from rock-cut architecture to stone temples. The Shore temple is an example of the later period of Pallava architecture. The figural canon in the Shore Temple of Mahabalipuram varies to a certain extent from the earlier architecture. The figure of the triumphant goddess of the Shore temple has a militant vigor conveyed by the moving pretense and the deploy¬ment of the arms in a kind of aureole. This is combined with a proposition of absolute seren¬ity and feminine softness, as is entirely appro¬priate to the notion of the divinity. The temple was planned in such a way that the door of the sanctuary opened to the east, in order to catch the first rays of the rising sun. This in itself resulted in a rather unusual arrangement, since it required the placing of the mandapa and the temple court at the rear or west end of the main sanctuary. The terraced spires crowning both shrine and porch very visibly reveal an expansion from the form of the Dharmaraja rath. In the Shore Temple, however, the depen¬dence on the vihara type is less marked, owing to the prominence on the height and slender-ness of the tower, like an attenuated version of the Dharmaraja rath. Actually, the character¬istic Dravidian form of a terraced architecture with the shape of the terminal stupika echoed in lesser replicas on the successive terraces still prevails, but these recessions are so ordered as to emphasise the verticality of the structure as a whole. Such distinguishing elements of the Pallava style as the pilasters with the extensive lions continue in the decoration of the portico of this structural monument.

The Kailasnatha temple at Kanchipuram is yet another architectural evidence of the Pallava dynasty. It dates back to 700 A.D. The architecture of the building consists of a sanctuary, a connecting pillared hall and a rectangular courtyard surrounding the entire complex. The pyramidal tower of the main shrine is again very obviously a development out of the Dharma¬raja rath. The storeys are manifested by heavy cornices and stupikas echoing the form of the cupola. There are a group of supplementary shrines around the base of the central spire that rhythmically reiterate the form of the terminal stupika. This shape is repeated once more in the row of cupolas crowning the ramparts of the patio. The gateways of the enclosure, surmounted by hull-shaped members of the vesara type repeating the form of Bhima`s rath at Mamallapuram, suggest the form of the temple towers of the last phase of Hindu architecture at Madura. As in the Shore Temple, pillars rising from rampant leonine forms are employed throughout.

The architecture of the Pallava dynasty was noteworthy because of it followed the idiom of Dravidian art and sculpture. The magnificent architecture of Mahabalipuram and Kanchipuram establish the foundation of the classical Dravidian architecture.

Religion in the Pallava Dynasty

Religion was most pervasive during the Pallava period. The Jains and the Buddhists seem to have become powerful and entrenched in royal courts during the fag end of the Kalabhra period. Therefore, Saivism of the early 7th century A.D. became quite aggressive and fought out the issue with the heretics.

Religion was most pervasive during the Pallava period. The Jains and the Buddhists seem to have become powerful and entrenched in royal courts during the fag end of the Kalabhra period. Therefore, Saivism of the early 7th century A.D. became quite aggressive and fought out the issue with the heretics.

Owing to the conflicts between the Saivites and the other religious sects the entire Pallava period was preparatory to that consummation which was to come after Sankara. The Pallava family worshipped different Gods at different times. Mahendravarman was first a Jaina and then a Saiva, Paramesvaravarman was a Saiva, Rajasimha`s name was Narasimhavarman (quite common among the Pallavas) but he built a temple for Kailasanatha (Siva). Nandivarman whose earlier name was Paramesvara built a temple for Vaikuntha Perumal (Vishnu). This certainly is different from the religious affiliation which characterized the Cholas from Aditya I to Kulottunga II, which was nearly fanatical Saivism.

The Bhakti movement is the name generally given to the activities of the Alvars and the Nayanmars. The movement itself achieved the sophistication of these two Hindu sects especially the Saivite. The Kalamukhas and the Pasupatas were two ferocious primitive Saivite sects, which indulged in orgies including human sacrifice. The Nayanmars created a sophisticated type of Bhakti Saivism whose chief slogan was `love is Siva`. They had to fight on two fronts i.e., while they were reforming the crude sects among themselves they had to deal with the then dominant Jainism and Buddhism while taking care not to forget the potential Vaishnavite hostility.

The two Bhakti streams, however collectively achieved a marvellous new atmosphere of God - consciousness among the people. A straight product of the Bhakti movement was the construction of a number of temples dedicated either to Siva or to Vishnu. It is said that Cholan Senganan caused a number of Siva temples to be constructed in the Chola country. The kings constructed many new temples and some of the older ones were made centres of religious edu cation. Of these the pride of place goes to Chidambaram, which later in Chola times was to become even a secondary capital. The Bhakti movement could be traced back to the Bhagavad Gita that was given a new and monistic interpretation by Sankaracharya of Kaladi. He attempted a philosophical justification of Smartaism.

Civilization and Culture of the Pallavas

The Pallava rule formed a golden epoch in the cultural history of south India. The period under the Pallavas was marked by considerable literary activities and cultural revival. The Pallavas warmly patronized Sanskrit language and most of the literary records of the time were composed in that language. Due to the cultural renaissance and a great revival of the Sanskrit language a galaxy of scholars flourished during the Pallava era, which accentuated the literary and cultural development in Southern India. Tradition referred that Simhavishnu, the Pallava king invited the great poet Bharvi to adorn his court. Dandin, the master of Sanskrit prose probably lived in the court of Narasimhavarmana II. Under the royal patronage, Kanchi became the seat of Sanskrit language and literature. The core of learning and education, Kanchi became the point of attraction for the literary scholars. Dinanaga, Kalidasa, Bharvi, Varahamihir etc were the distinguished person with enormous talent in the Pallava country. Not only the Sanskrit literature, the Tamil literature also received a huge impetus during the Pallava period. "Maatavailasa Prahasana", written by Mahendravarmana became very popular. The famous Tamil classic "Tamil Kural was composed during the period under the royal patronage. Madurai became a great center of the Tamil literature and culture. The Tamil grammar "Talakappiam" and Tamil versical compilation "Ettalogai" etc were composed during the period. These were of immense literary importance.

The Pallava rule formed a golden epoch in the cultural history of south India. The period under the Pallavas was marked by considerable literary activities and cultural revival. The Pallavas warmly patronized Sanskrit language and most of the literary records of the time were composed in that language. Due to the cultural renaissance and a great revival of the Sanskrit language a galaxy of scholars flourished during the Pallava era, which accentuated the literary and cultural development in Southern India. Tradition referred that Simhavishnu, the Pallava king invited the great poet Bharvi to adorn his court. Dandin, the master of Sanskrit prose probably lived in the court of Narasimhavarmana II. Under the royal patronage, Kanchi became the seat of Sanskrit language and literature. The core of learning and education, Kanchi became the point of attraction for the literary scholars. Dinanaga, Kalidasa, Bharvi, Varahamihir etc were the distinguished person with enormous talent in the Pallava country. Not only the Sanskrit literature, the Tamil literature also received a huge impetus during the Pallava period. "Maatavailasa Prahasana", written by Mahendravarmana became very popular. The famous Tamil classic "Tamil Kural was composed during the period under the royal patronage. Madurai became a great center of the Tamil literature and culture. The Tamil grammar "Talakappiam" and Tamil versical compilation "Ettalogai" etc were composed during the period. These were of immense literary importance.

From the 6th century AD, due to the Sanskrit revival, long poetical composition replaced the earlier style of the short poetry. Poetry was written according to the taste of the sophisticated and aristocratic people of the society. The "Silappadigaram" is one of such work suited to the taste of the sophisticated, educated people of the Pallava era. One of the most important literary works of the time was "Ramayanam" by Kaban. This is known as the Tamil form and version of Ramayana, where the character of Ravana was painted with all the noble virtues in comparison to Rama. It is consistent with the Tamil tradition and Tamil ego against the Northern Ramayana by Valmiki. The Buddhist literary work "Manimekhala" and the Jaina poetical work "Shibaga sindamani" etc. also flourished during the period.

The devotional songs composed by Vaishnava Alavaras and the Saiva Nayanaras also shared a significant position in the cultural renaissance of the Pallava period. Appar, Sambandhar, Manikkabsagar, Sundar were some of the devotional Narayana poets who composed Tamil Stotras or hymns. Siva was the object of worship and love. Since the Pallava kings were great musicians themselves they were the great patrons of music. Several celebrated musical treatise were also composed under their patronage. During the time painting also received a great patronage from the Pallava kings. Specimen of the Pallava painting has been found in the Pudukottai State.

Civilization of the Pallava period was greatly influenced by the religious reform movement that swept over India during the eighth century. The wave of the reform movement was originated in the Pallava kingdom first. The Pallavas completed the Aryanisation of Southern India. The Jains who had entered south India earlier had set up educational centers at Madurai and Kanchi. They also made a massive use of Sanskrit, Prakrit and Tamil as the medium of their preaching. But in the competition with the growing popularity of the Brahmanical Hinduism, Jainism lost its prominence in the long run.

Mahendravarmana lost interest in Jainism and became a staunch follower and patron of Saivism. Consequently Jainism began to fade out and continued in diminishing glory in centers like Pudukottai and in the hilly and forest regions.

Buddhism, which had earlier penetrated in the south, fought against invading Brahmanism in the monasteries and public debates. The Buddhist scholars debated finer points of theology with Brahmanical scholars and mostly lost the ground.

The civilization of the Pallava period was marked by the tremendous ascendancy of the Hinduism, which has been branded by the modern historians as the victory of the northern Aryanism. It is said that the influx of the mlechcha Sakas, Huns and the Kushanas in Northern India had polluted the significance of the Vedic rites and religion. In order to protect the purity of Vedic religion many Brahmins migrated to Southern India and preached the Vedic Religion. Henceforth the civilization of Deccan or southern India was mostly influenced by the Brahmanical Hinduism. Pallavas became the patrons of the orthodox Vedic preachers. The performance of the horse sacrifices by the Pallava rulers testified the ascendancy of the Vedic civilization. The success of Hinduism was mostly caused by the royal patronage to this religion. Sanskrit was the vehicle of the Brahmanical thought. Hence both the Brahmanical religion and Sanskrit literature made a great progress during the Pallava period. Several centers for the Brahmanical study sprang up. These study centers were closely connected with the temple premises and were known as Ghetikas. The study of the Brahmanical scriptures and literatures was the order of the day. The Pallava kings in order to promote the Brahmanical civilization made land grants or agraharas to the maintenance of the educational institutions. In the 8th century AD, another significant Hindu institution called Mathas or monasteries were in vogue. They were a combination of temple, rest houses, educational centers, debating and discoursing centers and the feeding Houses. The university of Kanchi became the spearhead of Aryan-Brahmanical influences of the South. Kanchi was regarded as one of the sacred cities of the Hindus. The Pallava king though mainly were the worshippers of Vishnu and Siva, they were tolerant towards other religious creeds. Although the religions like Buddhism and Jainism lost its former significance during the Pallava era, yet the civilization of the Pallava period was marked by the multiethnicity promoted by the Pallava kings.

Kings of Pallava Dynasty

The account of the early Pallavas has not yet been adequately settled. The Prakrit and the Sanskrit charters simply cite the royal names, their non-political grants and nothing about their supremacy or their political achievements. The earliest credentials on the Pallavas are the three copperplate grants. All three belong to Skandavarman I and written in the Prakrit language. Skandavarman extended his dominions from the Krishna in the north to the Pennar in the south and to the Bellary district in the West. He performed the Aswametha and other Vedic sacrifices. Toward the commencement of their rule, Manchikallu, Mayidavoiu, Darsi and Ongolu were the centers of their activity. Kanchipuram gained eminence as the center of their political and cultural activity by the second quarter of the fourth century CE.

Around 350 CE, Vishnugopa was overpowered by Samudragupta. With Samudragupta`s expedition, the Paliava conceal set in. In the reign of Simhavarman IV, who ascended the throne in 436 CE, the collapsed stature of the Pallavas was reinstated. He recovered the provinces lost to the Vishnukundins in the north, up to the mouth of the Krishna. The early Pallava history from this period onwards is furnished by a dozen or so copperplate grants. They are inscribed in the Sanskrit language and dated in the regal years of the kings.

With the succession of Nandivarman (480-500 CE), the turn down of the early Pallava family was seen. The Kadambas comprised of their hostility and captivated the nerve center of the Pallavas. In coastal Andhra the Vishnukundins founded their dominance. The Pallava authority was restricted to Tondaimandalam. With the accession of Simha Vishnu father of Mahendravarma I, probably in 575 CE, the magnificent colonial Pallava phase begins in the south.

The following chronology is accumulated from the three charters:

| Simhavarman I 275 - 300 CE | Simhavarman II 436 - 460 CE |

| Skandavarman | Skandavarman IV 460 - 480 CE |

| Visnugopa 350 - 355 CE | Nandivarman I 480 - 510 CE |

| Kumaravishnu I 350 - 370 CE | Kumaravishnu II 510 - 530 CE |

| Skandavarman II 370 - 385 CE | Buddhavarman 530 - 540 CE |

| Viravarman 385 - 400 CE | Kumaravisnu III 540 - 550 CE |

| Skandavarman III 400 - 436 CE | Simhavarman III 550 - 560 CE |

| Mahendravarman II 668 - 672 CE | Nandivarman II (Pallavamalla) 732 - 796 CE |

| Paramesvaravarman I 672 - 700 CE | Thandivarman 775 - 825 CE |

| Narasimhavarman II (Raja Simha) 700 - 728 CE | Nandivarman III 825 - 869 CE |

| Paramesvaravarman II 705 - 710 CE | Aparajitha Varman 882 - 901 CE |