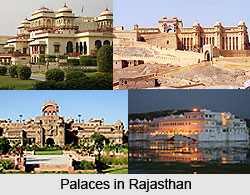

Architecture of Indian palaces is considered among the best in the world. There are two great period of palace building in India; the first is represented by the period of Mughal supremacy, from the middle parts of the sixteenth century to the middle parts of the eighteenth century, and the second to the British Raj. The famous forts of India were not mere strategic centres of defense. Some, such as the Maratha forts, were always intended mainly for military purposes but many were the architectural and social centerpiece of an entire state. This is particularly true of the Mughal and Rajput forts, which comprised concentrations of opulent public and private palaces of great splendour.

Architecture of Indian palaces is considered among the best in the world. There are two great period of palace building in India; the first is represented by the period of Mughal supremacy, from the middle parts of the sixteenth century to the middle parts of the eighteenth century, and the second to the British Raj. The famous forts of India were not mere strategic centres of defense. Some, such as the Maratha forts, were always intended mainly for military purposes but many were the architectural and social centerpiece of an entire state. This is particularly true of the Mughal and Rajput forts, which comprised concentrations of opulent public and private palaces of great splendour.

Some of the Hindu palaces or secular buildings have survived from before the mediaeval period. While it is evident from documentary and literary sources that these existed, the tradition of the perpetual reconstruction and recycling of existing masonry militated against the effective repair and conservation of secular buildings. One of the earliest is the renowned Man Mandir palace at Gwalior in the state of Madhya Pradesh, begun in about 1486 and representative of a distinctively independent thread in the Indian palace architecture.

In both the periods of palace building in India, the provision of an overriding central authority kept local rulers in check and fostered the growth of provincial elite who gained power and prestige as their local representatives. The great Rajput palaces represent the development of a separate architectural style of very considerable sophistication. In general, they share many common features. The major Rajput cities hold a principal palace, which was the chief residence of the Raja and his court. Generally, the palace was divided into two parts; the zenana or the quarters of women and the mardana or the quarters of men. The zenana was approached by a separate entrance and was normally closed to all men, other than a few selected eunuchs or courtiers. The minutely carved jali screens to the windows and balconies combined privacy and seclusion with the conditions of purdah.

The mardana in the palace was divided into state apartments and private rooms of the Raja. A majority of the palaces possess a Diwan-i-Am or Hall of Public Audience, where the Raja held court with his visitors or subjects. The Diwan-i-Khas or Hall of Private Audience was a chamber where he could confer with his advisers on state affairs. Often this serves the purpose of an apartment or private bedroom. The private rooms usually included a picture gallery or chitra shali, a bedroom and a temple. Where the private room was enriched with inlaid mirror work, it was known as sheesh mahal. The public rooms commonly included the daulat khana or treasury and the sileh khana or armoury.

Contemporary miniatures portray life in these palaces in great detail. They show rooms furnished with awnings, carpets, cushions and brocades, with embroidered canopies carried on poles, all enriched with sumptuous patterns and colours. There was very little solid furniture until the 19th century, when European patterns of taste started to prevail.

Contemporary miniatures portray life in these palaces in great detail. They show rooms furnished with awnings, carpets, cushions and brocades, with embroidered canopies carried on poles, all enriched with sumptuous patterns and colours. There was very little solid furniture until the 19th century, when European patterns of taste started to prevail.

The courtyards of the palace were utilized for a list of activities from royal audiences to religious festivals, while the rooftops and highest courtyards were used as outdoor bedchambers in hot weather conditions. This interplay of outdoor and indoor space was one of the hallmarks of the Indian palace architecture, where much more importance was given to the flow of cool air. Likewise, all the main apartments were designed for a versatility of use, so that each chamber or apartment could serve different variety of functions. Often, at Udaipur, Rajasthan or Bundi, for example, they were connected by narrow labyrinthine corridors with right-angle bends so that any insurgent enemy would be compelled to advance in single file through the tortuous palace complex.

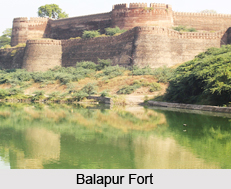

In almost all the Rajput cities the principal palace was also the central fortified citadel. Some were called garh palaces or fort-palace defended by vertiginous walls and impregnable gates. At Chitorgarh, Gwalior, Jaisalmer and Jodhpur, the fort-palace is located on a high hill which dominates the entire area. On the outer part, the lower storeys have few openings and little ornamentation, but above, these palaces break out into a marvelous skyline of balconies, cupolas, kiosks, turrets, etc, the product of incremental additions and accretions over many generations.

In the later palaces, modelled on those of the Mughal emperors at Agra and Delhi, the architectural design of the complex was one overall composition, with a huge outer wall enclosing several groups of buildings and gardens. At Alwar, Dungarpur and Jaipur, dispersed city palaces of this nature were copied by the local rulers from Mughal prototypes. Elsewhere, at Amber and Bundi, for instance, the garh palace is a part of a wider complex of fortifications. These great military citadels became symbols of the power and prestige of their respective rulers in the same way as the English country house was an expression of the social and political power of the English gentry.

Apart from the main palace complex, subsidiary secular buildings were erected for particular purposes. Pleasure palaces were built for picnics and shooting, or as hot-weather retreats. Normally, these form a sequence of open pavilions linked by gardens or ornamental pools. They were always comfortable, elegant expressions of royal patronage and power.

Within the main towns of Rajasthan, rich merchants and nobles resided in courtyard houses or havelis. These advanced houses, such as those at Jaipur and Jaisalmer, express the same architectural spirit as the great garh palaces. The four principal palaces of Bundelkhand, constructed during the 16th and early 17th centuries at Datia and Orchha, were notably different from the majority of the Rajput garh palaces in that they were conceived symmetrically both in their massing and plan form. Some have attributed this to the influence of Indian and lslamic architecture, others to the symbolism of an ancient Hindu mandala or Indian cosmic diagram. In reality they were a distinctive local manifestation of Rajput palace architecture.

In other parts of India surviving examples of palace architecture are comparatively rare. In Kashmir, the northern parts of India, the early palaces of the local rulers tended to reflect the simple vernacular style of the region. In the south, examples of palace architecture at Cochin and Padmanabhapuram were also derived from local architectural styles and idioms. The Marathas were more interested to construct isolated, inaccessible forts than in monumental palace architecture. Only two palaces of any significance were constructed, at Berar and Pune. Both were executed in carved teak and subsequently burnt down, so that the style was never copied.

With the establishment of British Empire in India, many rulers aspired to European ideals and consciously cultivated European and, in particular, English social habits which resulted in a vital change in the palace architecture in India. The old halls of audience were superseded by Durbar halls, where a ruler could receive his British overlords or representatives in an opulent setting. Guest-rooms were designed for European visitors with splendid collections of European art and furniture. Facilities were offered for their entertainment. Billiards rooms ballrooms, dining-rooms, swimming-pools and tennis courts reflected the interests and predilections of a new Western-educated generation of Indian rulers. Suites of French and English furniture and a large collection of antiques replaced the comfortable soft furnishings of the old garh palaces.

A number of these new palaces were designed by European architects or military engineers. The Lallgarh Palace at Bikaner was designed by the accomplished Sir Samuel Swinton Jacob.

The palace was designed as scholarly interpretations of existing native styles. Others were full-blown essays in European styles. The Elyscc palace at Kapurthala was modelled on Versailles. Italian Renaissance designs were employed at Cooch Behar, Gwalior, Indore and Porbandar, while the gifted Henry Lanchester constructed the colossal Umaid Bhawan palace for the Maharaja of Jodhpur as a monumental exercise in civic classicism. Sometimes a curious distorted romanticism prevailed. At Bangalore the Maharaja of Mysore erected a palace reminiscent of Windsor Castle, while another, the Lalitha Mahal, now a hotel at Mysore, boasted a centerpiece based on St Paul`s Cathedral.

The palace was designed as scholarly interpretations of existing native styles. Others were full-blown essays in European styles. The Elyscc palace at Kapurthala was modelled on Versailles. Italian Renaissance designs were employed at Cooch Behar, Gwalior, Indore and Porbandar, while the gifted Henry Lanchester constructed the colossal Umaid Bhawan palace for the Maharaja of Jodhpur as a monumental exercise in civic classicism. Sometimes a curious distorted romanticism prevailed. At Bangalore the Maharaja of Mysore erected a palace reminiscent of Windsor Castle, while another, the Lalitha Mahal, now a hotel at Mysore, boasted a centerpiece based on St Paul`s Cathedral.

With the growth and development of Indo-Saracenic styles of architecture in the later parts of the nineteenth century, many patrons felt there was no need to stick to one particular style. This at times led to a highly inventive blending of Western and Oriental design. The buildings of Major Charles Mant and, in particular, his palaces at Kolhapur and Baroda were ingenious attempts at an intermingling of styles and forms, but not all were characterized by either discipline or restraint. The Viceroy`s House in New Delhi, by Sir Edwin Lutyens, is simply one of the finest buildings of the 20th century, the stylistic experiments in the blending of Eastern and Western architecture which produced an extraordinary heritage of palace buildings unparalleled anywhere in the world.