Architecture of Delhi during the later Mughals, precisely after the period of 1739, was intimately based upon Persian invasions, a geographical entity, which virtually had changed the map of Delhi forever. In 1739, Nadir Shah had invaded Delhi. This was the city`s first invasion in almost two centuries. Beginning from Raushan ud-Daula`s Sunahri mosque (one of the leading amirs in the court of Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah), Nadir Shah had ordered the city plundered - a sack that had lasted less than twelve hours! Many were killed, regardless of religion. The markets and buildings in the vicinity of Chandni Chowk as well as the Red Fort had suffered irreparable damage. The psychological jolt given to the complacent citizens of Delhi was never fully forgotten. Poets many years later continued to lament this event as if it had happened yesterday. The Iranian plunderer had remained in the city for about two months, taking on his departure the money from the royal treasury, jewels, including Shah Jahan`s legendary Peacock Throne and the Koh-i Noor diamond - and many other valuables. However, the loss of this wealth, essentially non-circulating, ultimately had little impact on the city`s economy, since trade continued to prosper.

Architecture of Delhi during the later Mughals, precisely after the period of 1739, was intimately based upon Persian invasions, a geographical entity, which virtually had changed the map of Delhi forever. In 1739, Nadir Shah had invaded Delhi. This was the city`s first invasion in almost two centuries. Beginning from Raushan ud-Daula`s Sunahri mosque (one of the leading amirs in the court of Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah), Nadir Shah had ordered the city plundered - a sack that had lasted less than twelve hours! Many were killed, regardless of religion. The markets and buildings in the vicinity of Chandni Chowk as well as the Red Fort had suffered irreparable damage. The psychological jolt given to the complacent citizens of Delhi was never fully forgotten. Poets many years later continued to lament this event as if it had happened yesterday. The Iranian plunderer had remained in the city for about two months, taking on his departure the money from the royal treasury, jewels, including Shah Jahan`s legendary Peacock Throne and the Koh-i Noor diamond - and many other valuables. However, the loss of this wealth, essentially non-circulating, ultimately had little impact on the city`s economy, since trade continued to prosper.

Such an unprecedented and inconceivable act of sacrilege by Nadir Shah of Delhi, a place which was almost shorn from its erstwhile glory, was religiously upgraded under later Mughal architecture. As such, architecture of Delhi under later Mughal royalty, deserves to be specially mentioned. Delhi had recovered quickly and new buildings replaced those that were destroyed. The very patron who had provided the mosque from which Nadir Shah had issued his order for the destruction gave the city a second mosque, Raushan ud-Daula Zafar Khan had provided it in 1744-45. By now the former influential amir had fallen from favour and was no longer active in politics. His second mosque, like his first one, is acknowledged today as the Sunahri or Golden mosque, and, like it, was also built in honour of the religious figure Shah Bhik. Situated south of the Red Fort along the main road that led to the Delhi Gate of Shahjahanabad, it is a single-aisled three-bayed mosque. Originally it was surmounted with gilt, copper-faced domes. However, the metal was subsequently removed and placed on the mosque Raushan ud-Daula had constructed earlier in Chandni Chowk. In contemporary times even the domes are missing!

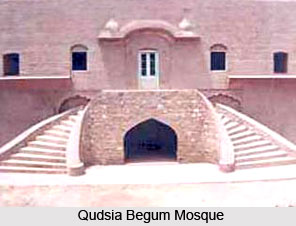

In 1748, Muhammad Shah was succeeded by his son, Ahmad Shah. The new ruler`s mother, Udham Bai, also recognised as Qudsiya Begum had wielded considerable influence over Ahmad Shah, as she had done in the early stages of Muhammad Shah`s reign when she was that ruler`s favourite consort. Now, in fact, the intelligent queen and her confidant, Javid Khan, the prime minister, held the true reins of power. Qudsiya Begum was an enthusiastic provider of Mughal architecture in Delhi for the later Mughals, best known for her palace and garden complex, Qudsiya Bagh. It was probably commenced when Ahmad Shah had assumed the throne in 1748. Located just north of Delhi`s walled city, this garden housed a substantial residence that overlooked the river Yamuna. The mansion has since been destroyed, but late 18th century engravings of its riverside facade indicate its splendour and magnitude. A large two-storied edifice, the mansion within the Qudsiya Bagh possessed polygonal turrets at every end. The facade was marked with projecting oriel windows, surmounted with sloped bangala-type roofs, indicating that this roof type continued to be used on secular architecture. In contemporary times, only an entrance gate and mosque remain, both manufactured of stucco-covered brick. Architecture of Delhi as a Mughal masterpiece during the later Mughals was indeed made possible even after the fact that a man like Nadir Shah had ransacked the sub-conscious of the entire Indian Mughal population.

Detailed ornamentation of the gate`s stucco work contributes to an overall elaborate appearance, rendering a fresh flamboyance to architecture of Delhi under the later Mughals. Beyond the gate lies the mosque, whose plan is similar to that of others of the later Mughal period. It is richly adorned with moulded and polychromed stucco, marked by elaborate faceted patterns and exaggerated floral designs found at the base and apex of arches. Engaged pilasters are flattened and highly articulated with chevron-like designs. Such ornamentation is usually termed `decadent`, as if to reflect Qudsiya Begum`s legendary individualistic character. In any event, this ornamentation is simply a more exuberant expression of that developed under the earlier Mughals.

During her son`s short reign, Qudsiya Begum had provided a second mosque, with Javid Khan, in 1750-51. Like the two mosques provided by Raushan ud-Daula, this one, too, is acknowledged as the Sunahri mosque after its once metal-plated domes. Located along the main road just south of the Shahjahanabad palace, the compound is entered by a red carved stone gate. The red stone mosque is small and delicate, though flanked on either side by enormously tall minarets. These and the bulbous domes underscore the mosque`s height, giving the small building a grandiose air - at times also revealing the reanimated architecture of Delhi during the later Mughals. The mosque is decorated with more subdued ornament than that of Qudsiya Begum`s private mosque on her mansion grounds.

During her son`s short reign, Qudsiya Begum had provided a second mosque, with Javid Khan, in 1750-51. Like the two mosques provided by Raushan ud-Daula, this one, too, is acknowledged as the Sunahri mosque after its once metal-plated domes. Located along the main road just south of the Shahjahanabad palace, the compound is entered by a red carved stone gate. The red stone mosque is small and delicate, though flanked on either side by enormously tall minarets. These and the bulbous domes underscore the mosque`s height, giving the small building a grandiose air - at times also revealing the reanimated architecture of Delhi during the later Mughals. The mosque is decorated with more subdued ornament than that of Qudsiya Begum`s private mosque on her mansion grounds.

In fact it is quite an acknowledged fact that Qudsiya Begum has been immortalised as a major renovator of architecture of Delhi under the later Mughal period and its consequent proceedings. The Begum also had built several structures at a Shia shrine known as Shahi Mardan in Delhi, approximately 9 km south of the walled city. These included an assembly hall, a mosque and tank as well as a walled enclosure. Little is known about the shrine before Qudsiya Begum`s patronage there, but it is probable that the queen mother had erected these structures to augment a certain Qadam Sharif, a building housing a footprint revered as that of Ali, who according to the Shia sect was the rightful successor of Muhammad. The current Qadam Sharif was built in 1759-60, probably renewing an older one. Although most of Qudsiya Begum`s buildings here have been rebuilt, her mosque remains a well-preserved illustration of 18th century religious architecture. It closely resembles the overall plan and elevation of her private Qudsiya Bagh mosque. The profuse stucco ornament is one element that is lacking here, suggesting that more austere decor was considered appropriate for public buildings such as the Sunahri mosque, built simultaneously. Qudsiya Begum`s patronage here may have been an attempt to lend this Shia shrine similar status to that enjoyed by Sunni shrines of Bakhtiyar Kaki and Nizam ud-Din.

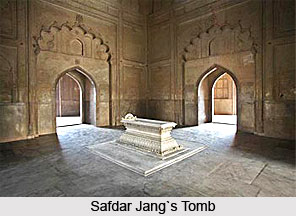

By the mid-18th century, Delhi was virtually all that remained of the once great and monumental Mughal Empire. Nevertheless, that now `small empire` and its `emperor` remained the model for Muslim culture and administration throughout north India. In Bengal and elsewhere, former provinces were transformed into autonomous states. In the case of Awadh, however, the ties with Delhi were broken gradually. For instance, Safdar Jang, the Mughal governor of Awadh, never regarded himself as independent, but part of the larger empire. After his death in 1754, his body was transported a considerable distance to the imperial capital, Delhi, which Safdar Jang always considered his home. There his son, Nawab Shuja ud-Daula had erected an enormous mausoleum. Such saddened information state that the gradually going defunct Mughal Empire still possessed its share of loyalists, with architecture of Delhi surfacing as a glorious instance. Delhi`s architecture during the later Mughals and after mid-18th century was no more solely rested in the hands of the Mughal realm itself, but also divided amongst the princely state nawabs.

Not only was Safdar Jang`s tomb built in the Mughal capital, it was, moreover, closely modelled on Humayun`s Tomb, the first imperial Mughal mausoleum. This square plan tomb is in the central attraction of a walled char bagh complex. Although the tomb`s layout, plan and its exterior, faced with pink and white stone, recall Humayun`s Tomb, Safdar Jang`s tomb bears many features characteristic of mid-eighteenth-century later Mughal architecture, concentrated in Delhi. These incorporate - complex stucco ornament on the interior, cusped rounded entrance arches, central pishtaqs surmounted by a series of bulbous domes and a central dome that rests on a tightly constricted drum. The structure presents a balance between increased surface articulation and mass.

Not only was Safdar Jang`s tomb built in the Mughal capital, it was, moreover, closely modelled on Humayun`s Tomb, the first imperial Mughal mausoleum. This square plan tomb is in the central attraction of a walled char bagh complex. Although the tomb`s layout, plan and its exterior, faced with pink and white stone, recall Humayun`s Tomb, Safdar Jang`s tomb bears many features characteristic of mid-eighteenth-century later Mughal architecture, concentrated in Delhi. These incorporate - complex stucco ornament on the interior, cusped rounded entrance arches, central pishtaqs surmounted by a series of bulbous domes and a central dome that rests on a tightly constricted drum. The structure presents a balance between increased surface articulation and mass.

Although the Mughal Empire became increasingly impotent politically, Delhi continued to flourish even into the late 18th century; such was the enigmatic qualities of Delhi and its charming attraction that had so much hooked the Mughals and their architectural basics. Much of Delhi`s architectural builds under later Mughals, during this time was financed by people employed by the British East India Company or by businessmen. Into the 19th century, the growth of wealthy Jain, Jat and other non-Muslim communities increased in the once-Oriental Mughal Delhi. In what was once the heartland of the Mughal Empire, these non-Muslims began construction of their own buildings that reflected Delhi`s new elite. For example, almost directly in front of the Shahjahanabad fort (the Red Fort) several Jain and Hindu temples were built, and elsewhere in the walled city, Hindu temples were erected in prolific numbers.

The later Mughal emperors and their subjects continued to build, although not as extensively as before. Architecture of Delhi under the later Mughals, indeed then stood at the crossroads, which has been historically related all through the colossal Mughal Empire from the early 16th century, from Babur. The gradual and understandable declination has been very much visible all through, perhaps mostly in the over-the-top domain of `Mughal architecture` and its influences upon the Indian population.

In 1803, the British gained control of Delhi and Mughal authority existed in the name alone. The Mughal emperors, however, assumed their regal responsibilities as best they could, for they remained symbols of a way of life and refined culture whose significance even the British had realised. As a result, the `last Mughals` and their dream of Delhi associated with the legacy of Mughal architecture continued in religious and palatial edifices when possible. In 1811, new stone masonry bridges replacing older wooden drawbridges were placed before the Lahore and Delhi Gates of the Shahjahanabad palace. Erected under the auspices of the later Mughal ruler Akbar II, their construction was supervised by an Englishman, Robert Macpherson. These immovable bridges thoroughly served British interests, for their presence meant that the fort (implying the Red Fort) could not be completely isolated by Mughal inhabitants. Indeed, British Raj intervention unto Delhi`s architecture was sort of a boon for later Mughals and their `regalia` to uphold rebirth of ancestral bloodline.

An increasing number of religious buildings were provided by citizens identified only by name. For instance, in 1837-38, Saddho, a woman who describes herself as a humble milkmaid, had erected religious structures within the old city that no longer remain. Still standing, however, is a red sandstone mosque built in 1822-23 by Mubarak Begum, known as Lai Kunwar, the consort of an Englishman residing in Delhi. This small single-aisled three-bayed mosque is probably the best surviving example of early 19th century Mughal architecture in Delhi under later Mughals in present times. Its facade is marked by rounded cusped arches, above which is a tri-lobed arch, whose central bay recalls the baldachin covering on Shah Jahan`s throne in his nearby Public Audience Hall (referring to the legendary Peacock Throne housed in the Diwan-i-Am in Red Fort). The interior transverse arches are tri-lobed - the shape of decorative arches on the mosque`s exterior. Tri-lobed arches also appear on the mihrab. The mosque`s interior is finely but chastely carved with shallow recessed arches and cusped niches. This small but well-balanced structure indicates a waning taste for highly ornate surfaces in Delhi, while in contemporary Lucknow and Murshidabad, Mughal desire for ornate surfaces was at a peak.

The last significant Mughal building erected within the old walled city is the mosque of Hamid Ah Khan, the prime minister of Bahadur Shah II (1837-57), the last Mughal emperor. Ha`mid Ali had built the mosque in 1841-42, not far from the Kashmir Gate. Its inscription was penned by Mirza Ghalib, the most famous poet of the times. This large mosque, positioned atop a raised platform, reveals a sense of spatial tension. Here, the emphasis is laid upon the horizontal, while spatial tension in the later 17th century possessed a vertical emphasis. Yet, the sense of visual imbalance is similar. The facade bears three large cusped entrance arches. The central bay of Hamid Khan`s mosque, marked with a large arch whose central lobe forms a curved cornice, harks back Shah Jahan`s throne in the nearby fort. Its flanking side-wings are surmounted with a parapet of miniature domes based on earlier Mughal entrance gates, in particular the entrance into the Taj Mahal.

The last Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah II, a sufi himself, had constructed his own red sandstone mansion, adjacent to the dargah of Bakhtiyar Kaki. It was recognised as Zafar Mahal after the king`s poetic name. It is however no accident that the residence was constructed close to the dargah. Just as tombs were built in the compounds of these shrines so that the interred might receive the divine power (baraka) of the saint, so the last Mughal, with little authority of his own, hoped to derive some from the inherent authority of the dargah. And ultimately, architecture of Delhi with the later and last Mughals, just as it had started with constructions of tombs and mosques, did also terminate with a similar structure.