About Architecture of Bihar

Bihar is a state in East India. It is the place where Buddhism and Jainism originated. Buddhist architecture in Bihar is seen in the ruins of the Nalanda and the Daibosatsuji Temple in Bodh Gaya. Vaishali in Bihar is the birth place of Mahavira and the Parasanad hills are a sacred place for Jains, but architecturally there is not much left here. From the 13th century Bihar came under the control of the Delhi sultans. They had developed an architectural style which is worth seeing, but they did not develop anything in the central provinces. It was the same during British rule too. Patna the capital of Bihar is also the land of Pataliputra, which was the capital of the old Magadha Empire.

Bihar is a state in East India. It is the place where Buddhism and Jainism originated. Buddhist architecture in Bihar is seen in the ruins of the Nalanda and the Daibosatsuji Temple in Bodh Gaya. Vaishali in Bihar is the birth place of Mahavira and the Parasanad hills are a sacred place for Jains, but architecturally there is not much left here. From the 13th century Bihar came under the control of the Delhi sultans. They had developed an architectural style which is worth seeing, but they did not develop anything in the central provinces. It was the same during British rule too. Patna the capital of Bihar is also the land of Pataliputra, which was the capital of the old Magadha Empire.

Bihar was known as Magadha during the ancient time and the Maurya Empire originated here. During the 5th and 6th centuries, the kingdom of Magadha was the cultural centre of Bihar. The Gupta Empire of Magadha is known as the golden age of India. The University of Nalanda was set up during this time. During the 16th century Bihar came under the supremacy of the Mughal Empire under Akbar. With the decline of the Mughal Empire, Bihar came under the dominions of the Nawab of Bengal.

There is a Stupa and stambha built in the place where Buddha spent his last rainy season in Vaishali. Emperor Ashoka built more than thirty such memorial pillars in different regions. A statue of an animal was often sculpted on top of the Stupa. This style originated in Persia and was later continued by Jains in south India. In Patna the Golghar is an eccentric dome like an inverted rice bowl which was used as a storehouse during famines. It is twenty seven meters high, built with brick and mortar and is devoid of any decorations. It has a staircase to the top and a hole on top, through which grain was poured in. The design is one of the functional doctrines of the middle Ages. Bodh Gaya is a pilgrim place with temples, stupas and monasteries. The place where Lord Buddha sat is now sacred. The surrounding stone fencing dates to the 2nd century. The large temple beside the Bodhi tree was built in the 7th century. Though half complete, it is important as a relic that depicts the exceptional quality of Buddhist construction. The temple has four small towers in each corner and is of the five shrine style. The small towers were added in the 19th century. The main tower is made of bricks and finished with plaster. The original tower was curved, resembling the shikharas of Hindu temples. At present most Buddhist countries have constructed temples in Bodh Gaya and it has become the meeting ground and extensive storehouse of various Buddhist architectural styles.

It has a staircase to the top and a hole on top, through which grain was poured in. The design is one of the functional doctrines of the middle Ages. Bodh Gaya is a pilgrim place with temples, stupas and monasteries. The place where Lord Buddha sat is now sacred. The surrounding stone fencing dates to the 2nd century. The large temple beside the Bodhi tree was built in the 7th century. Though half complete, it is important as a relic that depicts the exceptional quality of Buddhist construction. The temple has four small towers in each corner and is of the five shrine style. The small towers were added in the 19th century. The main tower is made of bricks and finished with plaster. The original tower was curved, resembling the shikharas of Hindu temples. At present most Buddhist countries have constructed temples in Bodh Gaya and it has become the meeting ground and extensive storehouse of various Buddhist architectural styles.

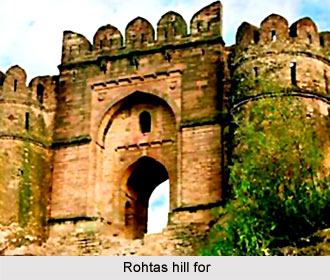

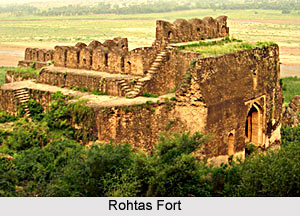

The Choti Dargah is the earliest examples of Islamic architecture in Patna. The Choti Dargah belongs to the Mughal era and is similar in style to the ones in Agra and Fatehpur Sikri. The base of the dome has pillars, beams and broad eaves. There is a closed corridor and a small mosque in the precincts. The top of the big minaret in the southeast corner is broken. Architecture in Bihar during Akbar was a domain which was principally focused and concentrated upon the legendary and historic Rohtas Fort, the one still instance which remains unconquered. The mosques in Rohtas were the ideal picture that Mughal architecture in Bihar had rested in the tremendous shoulders of Akbar`s aristocracy. However, outside the purview of Rohtas hill fort, Akbar`s architectural dexterity in Bihar is also noticed in places like Hajipur, Patna and Munger. The Gurudwara in Patna is built in the Mughal style. Architecture in Bihar during Jahangir bears much similarity and likeness with Bengal and its Indo-Islamic touch under Mughal hands.

During Emperor Ashoka`s reign, unique developments in Indian architecture started with the cave temples. There are seven cave temples surviving from the early days, on Barabar and Nagarjuni hills. These do not belong to the Buddhist religion but to a religion called Ajivika which was prevalent in those days. The caves are small and simple, with very little decoration, for example, the Lomas Rishi cave on the Barabar hills.

Architecture of Bihar During Later Mughals

The region of Bihar in eastern Indian purview was a crucial one which has arrested attention since the times of Gautama Buddha in pre-Christian era. Regarded as an abode of ancient architectural as well as a religious epitome, Bihar could never be ignored by the Mughals. They needed to keep the place as a stronghold in order to establish their supremacy in far-off regions from Delhi. Indeed, as with their predecessors, the later Mughals had also assayed to emphasise their superiority in Bihar architecturally. In a strange and uncanny matter of ancestral and progeny competition, architecture of Bihar during the later Mughals is an issue of considerable wonder and interest for researchers and historians and readers of Indian history in contemporary times.

The region of Bihar in eastern Indian purview was a crucial one which has arrested attention since the times of Gautama Buddha in pre-Christian era. Regarded as an abode of ancient architectural as well as a religious epitome, Bihar could never be ignored by the Mughals. They needed to keep the place as a stronghold in order to establish their supremacy in far-off regions from Delhi. Indeed, as with their predecessors, the later Mughals had also assayed to emphasise their superiority in Bihar architecturally. In a strange and uncanny matter of ancestral and progeny competition, architecture of Bihar during the later Mughals is an issue of considerable wonder and interest for researchers and historians and readers of Indian history in contemporary times.

The finest later Mughal mausolea in Bihar are modelled on the tombs of Iftikhar Khan in Chunar and Shah Daulat in Maner, each built during Jahangir`s reign. Amongst these are tombs erected for Shamsher Khan and Ibrahim Husain Khan, both following the plan and elevation of the tombs from Jahangir`s time, but embellished with motifs characteristic of eighteenth-century ornamentation. That is, each tomb possesses a domed central chamber surrounded by an open veranda. Ibrahim Husain Khan`s tomb in Bhagalpur bears no date, but its interior and exterior walls, ornately articulated with stucco ornament, reflect the increased surface elaboration seen in much eighteenth-century architecture across north India. Also demonstrating these new motifs is Shamsher Khan`s tomb, yet another imperative architectural piece of work in Bihar during the later Mughals. Amongst these new features was present the dome`s high drum with screens that is surmounted by bangala roofs. Shamsher Khan had served for some time as governor of Patna (then acknowledged as Azimabad) during the reign of Shah Alam Bahadur Shah. He, like his uncle, Daud Khan, had founded a town in his own name, Shamshernagar, not far from Daudnagar. There, Shamsher Khan had in fact built his own tomb, a serai (a rest house for travellers and caravans, built during Mughal era) and well before his death in 1712. Only the tomb remains though in present times, which can still be noted as one of the striving excellences of architecture of Bihar during the later Mughals.

In contrast to the fine late Mughal mausolea of Bihar is the austere Jami mosque of Silao in Nalanda District. This single-aisled three-bayed mosque, constructed in 1741-42 by a father and son, Sayyid Muhammad and Sayyid Ghulam Najaf, is enclosed by high walls, not common in eastern India during this time, yet one more feature of amalgamated architecture under later Mughals in Bihar. Each of the exterior walls bear inscriptions, again unusual for later Mughal architectural patterns in Bihar in eastern India. Like the exterior, the Jami mosque`s interior is sparsely ornamented. Cusped mihrabs (a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the qibla, i.e., the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca and hence the direction that Muslims should face while praying; the wall in which a mihrab appears is thus the "qibla wall") and a more complex form of pendentives than seen before in Bihar are the sole decorative devices in the Jami mosque of Silao. The contrast with such contemporary monuments as Ibrahim Husain Khan`s tomb in Bhagalpur indicates that in eighteenth-century Bihar no single ornamental style prevailed even under Mughal rule, probably because there was no single strong patron or model.

In contrast to the fine late Mughal mausolea of Bihar is the austere Jami mosque of Silao in Nalanda District. This single-aisled three-bayed mosque, constructed in 1741-42 by a father and son, Sayyid Muhammad and Sayyid Ghulam Najaf, is enclosed by high walls, not common in eastern India during this time, yet one more feature of amalgamated architecture under later Mughals in Bihar. Each of the exterior walls bear inscriptions, again unusual for later Mughal architectural patterns in Bihar in eastern India. Like the exterior, the Jami mosque`s interior is sparsely ornamented. Cusped mihrabs (a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the qibla, i.e., the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca and hence the direction that Muslims should face while praying; the wall in which a mihrab appears is thus the "qibla wall") and a more complex form of pendentives than seen before in Bihar are the sole decorative devices in the Jami mosque of Silao. The contrast with such contemporary monuments as Ibrahim Husain Khan`s tomb in Bhagalpur indicates that in eighteenth-century Bihar no single ornamental style prevailed even under Mughal rule, probably because there was no single strong patron or model.

Patna had remained Bihar`s leading commercial centre, a thing which has not changed in contemporary dates. The city was even enlarged under Prince Azim al-Shan, governor of Bihar during the early eighteenth century. Azim al-Shan had renamed Patna city as `Azimabad`, proclaiming his desire to give birth to a second Delhi. His efforts had failed though, as did his bid for the throne, but Patna still continued to benefit from the patronage of political figures and wealthy merchants. Amongst the structures they had provided, the most elegant is the mosque of Mir Ashraf, constructed by a Patna businessman in 1773-74. Its articulated facade with petal-like kungura, cartouches and arched niches is characteristic of those seen throughout India in the 18th century, much near to later Mughal rule from the British invasion. As such, tempted to be reiterated over and over, architecture of Bihar during later Mughals was an emulation and imitation of the earlier Mughals in every respect, though not even near to such masterworks. The interior of Mir Ashraf`s mosque, too, emotes ornateness from each angle, for cartouches and arch motifs embellish the walls and dome. The floor of the prayer chamber is composed of multicoloured tiles of the sort used on pre-Mughal Bengali structures. This unique flooring is in keeping with the mosque`s articulated surfaces, related to that of contemporary architecture in Murshidabad, for example, Munni Begum`s Chowk mosque erected in 1767.

Patna had remained Bihar`s leading commercial centre, a thing which has not changed in contemporary dates. The city was even enlarged under Prince Azim al-Shan, governor of Bihar during the early eighteenth century. Azim al-Shan had renamed Patna city as `Azimabad`, proclaiming his desire to give birth to a second Delhi. His efforts had failed though, as did his bid for the throne, but Patna still continued to benefit from the patronage of political figures and wealthy merchants. Amongst the structures they had provided, the most elegant is the mosque of Mir Ashraf, constructed by a Patna businessman in 1773-74. Its articulated facade with petal-like kungura, cartouches and arched niches is characteristic of those seen throughout India in the 18th century, much near to later Mughal rule from the British invasion. As such, tempted to be reiterated over and over, architecture of Bihar during later Mughals was an emulation and imitation of the earlier Mughals in every respect, though not even near to such masterworks. The interior of Mir Ashraf`s mosque, too, emotes ornateness from each angle, for cartouches and arch motifs embellish the walls and dome. The floor of the prayer chamber is composed of multicoloured tiles of the sort used on pre-Mughal Bengali structures. This unique flooring is in keeping with the mosque`s articulated surfaces, related to that of contemporary architecture in Murshidabad, for example, Munni Begum`s Chowk mosque erected in 1767.

Whether ornate or austere, religious architecture in Bihar under the later Mughals, as in Awadh and Murshidabad, reveals virtually no European influence. The Bawli Hall mosque on the estate of a 19th century residence, for instance, displays the features of Mughal architecture. The mosque`s central facade owns a rather lobed entrance arch and a parapet of domed kungura, recalling features of the 1841-42 mosque of Hamid Ali Khan, Delhi`s last significant Mughal mosque. No European forms had been utilised on the Bawli Hall mosque; rather, its design reflects contemporary work at the Mughal capital more than anything seen in the closer centres of Awadh and Murshidabad. By contrast, the residence reveals considerable European influence following patterns set forth in Lucknow and Murshidabad and the nawab architectural framework post the architectural waning wonders of Bihar during later Mughal rule. Bawli Hall, the nineteenth-century residence of Nawab Luft Ali Khan, once had served as an extensive mansion little different from contemporary British buildings in India. Abandoned in present times, the Hall demonstrates the extent that British architecture served as the model for houses of important figures in later Mughal successor states.

Architecture in Bihar During Akbar

In Bihar province, the most important work of Akbar`s time was in the hill fort of Rohtas. In 1576, Akbar`s troops had captured Rohtas from rebel Afghan forces and had utilised the hill fort, some 45 km in circumference, as a garrison pivotal in controlling the rest of eastern India. As such, architecture in Bihar during Akbar comes down as a crucial point of time in Mughal architecture in Bihar, which was pivotal to the ruling and administration of the Mughal Empire from far-off Delhi/Agra.

In Bihar province, the most important work of Akbar`s time was in the hill fort of Rohtas. In 1576, Akbar`s troops had captured Rohtas from rebel Afghan forces and had utilised the hill fort, some 45 km in circumference, as a garrison pivotal in controlling the rest of eastern India. As such, architecture in Bihar during Akbar comes down as a crucial point of time in Mughal architecture in Bihar, which was pivotal to the ruling and administration of the Mughal Empire from far-off Delhi/Agra.

Although the fort of Rohtas had served as an important fort under the Suri dynasty (made legendary by the daring debonair Sher Shah Suri), the Mughals had developed a different portion of the fort. There actually exists a palace at Rohtas Fort that Raja Man Singh (one of a Hindus in the court of the Muslim Akbar and one of his highest ranking amirs) had erected, but it was not the first Mughal building in the fort. A mosque had been built in 1578, only two years after the fort became strictly Mughal in art after Sher Shah. Indeed, architecture in Bihar during Akbar grossly had revolved around the highly invincible and unassailable Rohtas Fort, shrouded with legends. After all, the mosque in Rohtas was the first Mughal monument in all Bihar provinces. Built by an Akbar loyalist, Habash Khan, who had died defending Rohtas against renegade Mughal amirs and Afghan rebels, the mosque is similar in appearance to the Jami mosque constructed on the hill thirty-five years earlier by Haibat Khan, one of Sher Shah Suri`s leading generals.

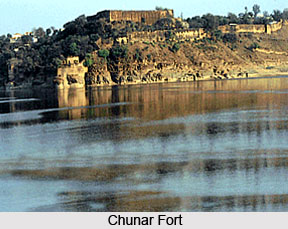

Both of the mentioned mosques adhere to a single-aisled three-bayed rectangular plan. Differences that lie till today are indeed slight. The central pishtaq of the Mughal mosque is lower and its facade bears intricately carved panels, recalling similar work on a gate at the Chunar Fort under Akbar. Although the Mughal mosque in Rohtas resembles the earlier Afghan one, situated approximately 3 km away, it bears an inscription over the central entrance arch that might be interpreted as a poignant statement of Mughal supremacy. Opening with the Quranic phrase, "With God`s help victory is imminent," most of this Persian inscription refers to Akbar`s victories and concludes with an appeal, in Arabic, to "deliver this good news to believers." Considering the wobbly political situation during that time, the inscription is mostly interpreted as a proclamation of Mughal authority over rebels in Bihar. Rebellious intervention was one major factor which was most commonplace during emperor`s Akbar`s time and his architectural circulation in eastern India. Yet, overlooking every kind of hardship, architecture in Bihar during Akbar was handsomely accomplished by the honest nobility and patronaged amirs who were brought under the good-will of the emperor regularly from the Mughal court.

Both of the mentioned mosques adhere to a single-aisled three-bayed rectangular plan. Differences that lie till today are indeed slight. The central pishtaq of the Mughal mosque is lower and its facade bears intricately carved panels, recalling similar work on a gate at the Chunar Fort under Akbar. Although the Mughal mosque in Rohtas resembles the earlier Afghan one, situated approximately 3 km away, it bears an inscription over the central entrance arch that might be interpreted as a poignant statement of Mughal supremacy. Opening with the Quranic phrase, "With God`s help victory is imminent," most of this Persian inscription refers to Akbar`s victories and concludes with an appeal, in Arabic, to "deliver this good news to believers." Considering the wobbly political situation during that time, the inscription is mostly interpreted as a proclamation of Mughal authority over rebels in Bihar. Rebellious intervention was one major factor which was most commonplace during emperor`s Akbar`s time and his architectural circulation in eastern India. Yet, overlooking every kind of hardship, architecture in Bihar during Akbar was handsomely accomplished by the honest nobility and patronaged amirs who were brought under the good-will of the emperor regularly from the Mughal court.

However, in association with Bihar`s architecture during Akbar and the mass connection with the fort of Rohtas, a single mosque is not enough to suggest an urban setting, the mosque which was erected by Habash Khan. There were, however, other Akbari structures on the Rohtas hill, which indicate the presence of a permanent and continuous large population. By far the largest and most important of these is the palace of Raja Man Singh. Numerous smaller buildings, mostly tombs, remain in the vicinity of the palace and Habash Khan`s mosque. Amongst these are a chattri and an unusual wall mosque, serving as the tomb of Saqi Sultan, who had expired in 1579-80, before he could attain the title khan, which he greatly coveted. Further testimony to the fort`s large population is a service town at the foot of the hill. It was - and still is - called `Akbarpur`, after the then-ruling monarch. Thus, although relatively inaccessible and robustly fortified, Rohtas Fort appears to have functioned as a major urban centre as long as it remained a significant administrative centre.

However, in association with Bihar`s architecture during Akbar and the mass connection with the fort of Rohtas, a single mosque is not enough to suggest an urban setting, the mosque which was erected by Habash Khan. There were, however, other Akbari structures on the Rohtas hill, which indicate the presence of a permanent and continuous large population. By far the largest and most important of these is the palace of Raja Man Singh. Numerous smaller buildings, mostly tombs, remain in the vicinity of the palace and Habash Khan`s mosque. Amongst these are a chattri and an unusual wall mosque, serving as the tomb of Saqi Sultan, who had expired in 1579-80, before he could attain the title khan, which he greatly coveted. Further testimony to the fort`s large population is a service town at the foot of the hill. It was - and still is - called `Akbarpur`, after the then-ruling monarch. Thus, although relatively inaccessible and robustly fortified, Rohtas Fort appears to have functioned as a major urban centre as long as it remained a significant administrative centre.

While Rohtas was an important military headquarters, it was the cities of Hajipur, Patna and Munger, situated on the Ganges, as well as Bihar Sharif, the traditional administrative centre of Bihar and long a site of tremendous religious importance, that were the major urban settlements, likewise serving as the most strategic architectural governance in Bihar during Akbar. Inscriptions indicate Akbari-period building activity in all of them, excluding Patna.

Hajipur, situated at the confluence of the Gandak River and Ganges, across from Patna, was considered the key to north Bihar. The city had been the land-holding of Said Khan, who on three separate occasions had served as the governor of Bihar. Here in 1586-87, during Said Khan`s first period of governorship, his brother Makhsus Khan had erected a mosque, the second recognised Mughal mosque in Bihar, a classic instance of Mughal architecture of Bihar during Akbar. Although Makhsus Khan`s mosque`s facade and entrance gate were seriously ravaged in the 1934 earthquake, the original layout is intact and the interior appears little changed. The mosque`s adherence to olden Afghani style mosques as well as its Bengali forms, for instance, the minbar (a pulpit in the mosque where the Imam (leader of prayer) stands to present sermons) and curved cornice of the entrance gate, hints a reliance upon local designers, a particular Mughal architectural feature that has come down since the age of Babur. The link with Bengal in particular is not surprising since Hajipur, often in Bengali hands, was a decisive naval headquarters under the pre-Mughal Husain Shahi dynasty. Thus in Bihar, except for Raja Man Singh`s outstanding patronage, Mughal architectural design remained primarily `conservative`.

Architecture of Bihar During Aurangzeb

Emperor Aurangzeb was much less involved in architectural production as compared to his predecessors, but he did sponsor some significant monuments, especially religious ones. Indeed, religious monuments and spiritualistic architecture in Bihar was one domain, which is most visible under Aurangzeb`s rule. Early during Aurangzeb`s reign, the harmonious balance of Shah Jahani-period architecture was rejected in support of an increased sense of `spatial tension` with vehemence on height. Stucco and other less expensive materials trying to outperform the marble and inlaid stone of earlier periods cover built surfaces under Aurangzeb. Immediately after Aurangzeb`s accession, the utilisation of forms and motifs, such as the baluster column and the bangala canopy, earlier reserved for the ruler alone, are visible on non-imperially sponsored monuments. This suggests both that there was relatively little imperial interference in architectural patronage and that the vocabulary of imperial and divine symbolism established by Shah Jahan was rather `devalued` by Aurangzeb. At the same time, architectural activity by the nobility had proliferated like never before - a fact which was mostly accentuated in architecture in Bihar during Aurangzeb, which can be comprehended as under. This very fact suggests that the noblemen and Aurangzeb`s Mughal court viziers were much eager and enthusiastic to fill in the `architect`s` role, previously dominated by the emperor.

Emperor Aurangzeb was much less involved in architectural production as compared to his predecessors, but he did sponsor some significant monuments, especially religious ones. Indeed, religious monuments and spiritualistic architecture in Bihar was one domain, which is most visible under Aurangzeb`s rule. Early during Aurangzeb`s reign, the harmonious balance of Shah Jahani-period architecture was rejected in support of an increased sense of `spatial tension` with vehemence on height. Stucco and other less expensive materials trying to outperform the marble and inlaid stone of earlier periods cover built surfaces under Aurangzeb. Immediately after Aurangzeb`s accession, the utilisation of forms and motifs, such as the baluster column and the bangala canopy, earlier reserved for the ruler alone, are visible on non-imperially sponsored monuments. This suggests both that there was relatively little imperial interference in architectural patronage and that the vocabulary of imperial and divine symbolism established by Shah Jahan was rather `devalued` by Aurangzeb. At the same time, architectural activity by the nobility had proliferated like never before - a fact which was mostly accentuated in architecture in Bihar during Aurangzeb, which can be comprehended as under. This very fact suggests that the noblemen and Aurangzeb`s Mughal court viziers were much eager and enthusiastic to fill in the `architect`s` role, previously dominated by the emperor.

The flourishing trade of Bihar and the relatively calm political climate had made conditions here much ripened for building activity. For instance, Daud Khan Quraishi, governor of Bihar from 1659 to 1664, had provided structures himself and by example had encouraged others to do so as well. Daud Khan Quraishi indeed had ended the last significant source of on-going opposition to Mughal authority in Bihar by conquering Palamau, inhabited by Chero rajas. Inside the Cheros` seventeenth-century fort, whose elegant gates had been constructed during Shah Jahan`s reign, Daud Khan had constructed a brick mosque in 1660. A single-aisled three-bayed structure surmounted by three low rounded domes, this mosque lacks the sophistication of the fort itself and other contemporary projects, possibly a result of its hasty construction. Nevertheless, it did serve as a powerful indicator of Mughal presence in this newly conquered territory. Indeed, Aurangzeb was so careful and meticulous about his eastern Indian architectural concern, that architecture in Bihar during Aurangzeb was masterfully handled by his positioned governing men, instances of which can be still be seen, standing tall and imposing.

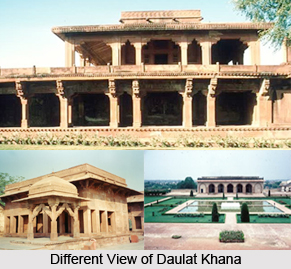

Daud Khan`s serai (a rest house for travellers and caravans, erected during Mughal era), in contrast to his Palamau mosque, is finely built. He had constructed it with the emperor`s permission for the protection of travellers in a robber infested area. This brick serai is in the town still referred to as Daudnagar (Aurangabad District). It remains today as the best-preserved example of seventeenth-century secular architecture in Bihar under Aurangzeb. The serai is entered on the east and west sides by arched portals with chamfered sides, harking back early statelier Mughal portals at the Ajmer Fort, built around 1570. Details, however, such as the stone pillars and cusped arches recalling those on the Sangi Dalan, built about a decade earlier in Rajmahal possess a more contemporary air. So do the small domed chattris atop the portal roof that probably derive from those on the gateway into the Taj Mahal complex.

Daud Khan`s serai (a rest house for travellers and caravans, erected during Mughal era), in contrast to his Palamau mosque, is finely built. He had constructed it with the emperor`s permission for the protection of travellers in a robber infested area. This brick serai is in the town still referred to as Daudnagar (Aurangabad District). It remains today as the best-preserved example of seventeenth-century secular architecture in Bihar under Aurangzeb. The serai is entered on the east and west sides by arched portals with chamfered sides, harking back early statelier Mughal portals at the Ajmer Fort, built around 1570. Details, however, such as the stone pillars and cusped arches recalling those on the Sangi Dalan, built about a decade earlier in Rajmahal possess a more contemporary air. So do the small domed chattris atop the portal roof that probably derive from those on the gateway into the Taj Mahal complex.

A second illustrious instance of secular architecture in Bihar under Aurangzeb was built in Bihar Sharif for Shaikha, a member of the Afghan Ghakkar tribe, many of who had lived in Bihar since the early 16th century. Referred to as the Nauratan, it was built in 1688-89. The main building in the Nauratan compound is a single-storied flat-roofed square-plan structure. The interior arrangement, however, is familiar throughout Mughal India. That is, a central domed chamber is surrounded by eight ancillary vaulted rooms, a total of nine chambers, the source of the building`s name, Nauratan, or nine jewels. Beside this building, others in the compound include a tank with underground chambers, a mosque and domestic quarters, some of which are still extant. The building, serving as a school in present times, provides an exceptional view of the penchants of the upper class during the late 17th century.

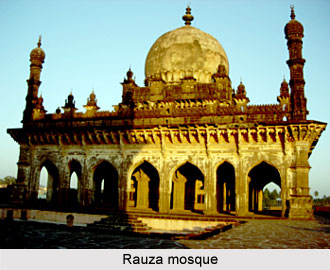

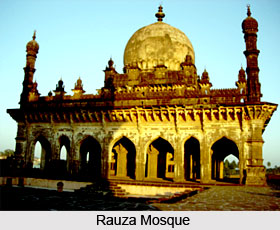

Throughout the `last Mughal` Aurangzeb`s reign, buildings were constructed in Patna, the capital of Bihar. Only one of them, however, is credited, at least by its inscription, to Aurangzeb as the emperor himself. The building being discussed under scanner is the Rauza mosque, dated 1667-68. It is, in fact, the only Mughal building in all Bihar that claims imperial Mughal sponsorship. This simple single-aisled three-bayed Rauza mosque was built in conjunction with the graves of two saints. It adheres closely to the form established by the early 17th century mosque of Mirza Masum. In spite of the brief inscription, the Rauza mosque`s unostentatious style and plan evoke that it was built in response to a general order encouraging the construction of mosques, but was not actually paid for by the ruler. Now the matter that strikes a reader the most might be that Mughal architecture in Bihar, precisely in Patna during Aurangzeb was nearly accomplished in absence of the emperor himself! Aurangzeb, its is known never had been in Patna, nor did he construct mosques at sites with which he did not have a strong personal interest.

Throughout the `last Mughal` Aurangzeb`s reign, buildings were constructed in Patna, the capital of Bihar. Only one of them, however, is credited, at least by its inscription, to Aurangzeb as the emperor himself. The building being discussed under scanner is the Rauza mosque, dated 1667-68. It is, in fact, the only Mughal building in all Bihar that claims imperial Mughal sponsorship. This simple single-aisled three-bayed Rauza mosque was built in conjunction with the graves of two saints. It adheres closely to the form established by the early 17th century mosque of Mirza Masum. In spite of the brief inscription, the Rauza mosque`s unostentatious style and plan evoke that it was built in response to a general order encouraging the construction of mosques, but was not actually paid for by the ruler. Now the matter that strikes a reader the most might be that Mughal architecture in Bihar, precisely in Patna during Aurangzeb was nearly accomplished in absence of the emperor himself! Aurangzeb, its is known never had been in Patna, nor did he construct mosques at sites with which he did not have a strong personal interest.

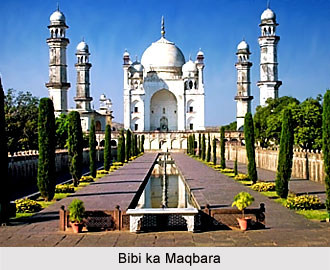

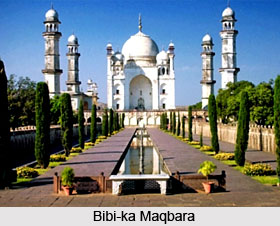

Unlike the simple and humble Rauza mosque, one constructed nearly twenty years later by Khwaja Amber in the service of the empire`s highest-ranking noble, Shaista Khan, features the most elaborate stucco work on any Patna structure of this time. However, the decor of this mosque, dated 1688-89, is considerably more subdued and rather low-key as opposed to contemporary ornamentation elsewhere. Here in the mosque of Khwaja Amber - a noted instance of Aurangzeb`s patronage in Mughal architecture in Bihar, only the interior of the domes is intricately embellished, bringing to mind similar designs on the Benaras Jami mosque or the Bibi-ka Maqbara in Aurangabad, built at the beginning of Aurangzeb`s reign. This contrasts with the more characteristically austere architecture of Mughal Bihar highly not under Aurangzeb - generally unembellished by contrast with contemporary architecture in the Mughal Bengal capitals of Dhaka or Rajmahal.

Architecture of Bihar During Shah Jahan

When still a young prince, Shah Jahan had rebelled against his father and Mughal emperor Jahangir in 1623, which is intimately associated with his consequent architecture in Bihar. Eventually, Shah Jahan is also known to have taken Burdwan in Bengal and then had established a counter-court in Rajmahal (in Bihar). Subsequently, Shah Jahan had spent time at Rohtas, where his son Murad Bakhsh was born. After his accession in 1628, however, Shah Jahan never had returned to the eastern hinterlands, with reason not known to the modern world. Instead, powerful and effective agents such as his son Prince Shah Shuja, Shaista Khan and Saif Khan were entrusted with their administration in Bihar and other parts of eastern India.

When still a young prince, Shah Jahan had rebelled against his father and Mughal emperor Jahangir in 1623, which is intimately associated with his consequent architecture in Bihar. Eventually, Shah Jahan is also known to have taken Burdwan in Bengal and then had established a counter-court in Rajmahal (in Bihar). Subsequently, Shah Jahan had spent time at Rohtas, where his son Murad Bakhsh was born. After his accession in 1628, however, Shah Jahan never had returned to the eastern hinterlands, with reason not known to the modern world. Instead, powerful and effective agents such as his son Prince Shah Shuja, Shaista Khan and Saif Khan were entrusted with their administration in Bihar and other parts of eastern India.

During Shah Jahan`s reign, Patna had remained the primary city in Bihar Province. Saif Khan - governor there from 1628 until 1632, had performed much to enhance the city, paralleling his earlier largess when he was Jahangir`s governor of Gujarat. To mention some of the meritorious instances of Bihar`s architecture during Shah Jahan, Saif Khan indeed acknowledged to have built grand mansions, though they no longer survive and at least two religious structures. One is an Idgah that he had provided in 1628, his first year as governor of Bihar. The central bay of its qibla wall, the only wall of this Idgah, is higher than the successively lower flanking ones. It contains a deeply recessed tri-partite mihrab whose demi-dome is marked by netted vaulting. Each side of the wall of this unusual Idgah possesses an intermeshed octagonal turret. This feature, witnessed earlier in Mughal architecture of Bihar and Bengal, such as Farid Bukhari`s Bihar Sharif mosque and the Hajipur Jami mosque, is derived from the region`s pre-Mughal Islamic buildings. This is yet another aspect that architecture in Bihar during Shah Jahan, or for that matter under any Mughal, was very much interlinked with pre-Mughali attempts in eastern parts of the country, a feature which is highly unlikely in Mughal architecture in Delhi or Agra.

Saif Khan also had provided a theological school (madrasa) to Bihar`s architecture under Shah Jahan, on the banks of the Ganges. Originally erected to house more than a hundred students, the madrasa complex was lined with large vaulted buildings, including a hammam. On the north side, overlooking the Ganges, are chattris to provide soothing shade. Next to the mosque on the west - yet another stellar presence of religious instance in eastern India`s architecture in Bihar during Shah Jahan, was a large double-storeyed entrance portal that Mundy describes as being `stately`. Despite its date of 1629, the mosque was still not accomplished in 1632, Mundy observed, although he indicates it was nevertheless in use. Foreign traders, for a fee, are known to have used the school for lodging.

Several mosques were constructed during this time along Patna`s main city street paralleling the Ganges, though only a few still remain. The best preserved instance of a mosque during Shah Jahan`s Mughal architecture in Bihar, is the masjid of Hajji Tatar. Exquisitely carved black stone frames the three arched entryways on the east façade. Such black stone was employed at times on Mughal structures in Bihar and Bengal, but was commonly found on the mosques of Bengal before Mughal times. It was never employed on structures outside the periphery of eastern India. The arched niches flanking the entrances of Hajji Tatar mosque and the facade`s ribbed engaged columns are typical of mid-seventeenth-century buildings in eastern India, for example on Habib Khan Sur`s mosque, built in 1638 at nearby Bihar Sharif. The mosque`s affiliations with local buildings are thus evident, despite its overall conformity with the prevailing Mughal aesthetic.

Several mosques were constructed during this time along Patna`s main city street paralleling the Ganges, though only a few still remain. The best preserved instance of a mosque during Shah Jahan`s Mughal architecture in Bihar, is the masjid of Hajji Tatar. Exquisitely carved black stone frames the three arched entryways on the east façade. Such black stone was employed at times on Mughal structures in Bihar and Bengal, but was commonly found on the mosques of Bengal before Mughal times. It was never employed on structures outside the periphery of eastern India. The arched niches flanking the entrances of Hajji Tatar mosque and the facade`s ribbed engaged columns are typical of mid-seventeenth-century buildings in eastern India, for example on Habib Khan Sur`s mosque, built in 1638 at nearby Bihar Sharif. The mosque`s affiliations with local buildings are thus evident, despite its overall conformity with the prevailing Mughal aesthetic.

Habib Khan Sur had held a position of great responsibility in Bihar and its architecture during Shah Jahah, especially during the frequent absences of the governor Saif Khan. Habib Khan had provided several works in Bihar Sharif, all in proximity to the dargah of Sharaf ud-Din Maneri (d. 1381) - one of the subcontinent`s most esteemed sufi saints. Amongst these is a refined mosque, dated 1638. This single-aisled three-domed mosque is modelled closely on Shaikh Farid Bukhari`s nearby Jahangiri-period mosque. It was thus almost certainly the product of a local, but expert architect. Several years later, in 1646, Habib Khan Sur had constructed a tank and Idgah near the shrine of saint Sharaf ud-Din. The Idgah though was crudely constructed, revealing none of the refinements of the patron`s earlier mosque, suggesting he had little role in its design.

Yet another structure influenced by those in Bihar Sharif, within the purview architecture in Bihar under Shah Jahan and his patronised men, is the mosque Raja Bahroz had constructed in Kharagpur in 1656-57. Kharagpur, today in Munger District, long had been the seat of a prominent Hindu family in Bihar. Although initially allied with the Mughals, the Kharagpur rajas were defeated by them during the late 16th century. One member of the family had acknowledged Mughal authority and had also converted to Islam. He was then reinstated on the Kharagpur throne. There, his successors had erected several mosques and many more tombs, suggesting that the newly converted Kharagpur rajas consciously had attempted to create a seat that very much had proclaimed their new religious affiliation.

Yet another structure influenced by those in Bihar Sharif, within the purview architecture in Bihar under Shah Jahan and his patronised men, is the mosque Raja Bahroz had constructed in Kharagpur in 1656-57. Kharagpur, today in Munger District, long had been the seat of a prominent Hindu family in Bihar. Although initially allied with the Mughals, the Kharagpur rajas were defeated by them during the late 16th century. One member of the family had acknowledged Mughal authority and had also converted to Islam. He was then reinstated on the Kharagpur throne. There, his successors had erected several mosques and many more tombs, suggesting that the newly converted Kharagpur rajas consciously had attempted to create a seat that very much had proclaimed their new religious affiliation.

The most magnificent amongst these Hindu-converted-Islam religious architecture by the Kharagpur rajas is Raja Bahroz`s single-aisled three-domed mosque. Situated just north of the raja`s palace on the bank of the river Man, the mosque is elevated on a high plinth - an increasingly common feature of later Mughal mosques. Visible from a great distance, this imposing mosque is the largest one built in eastern India since Raja Man Singh`s Jami mosque of c. 1600 in Rajmahal. The facade of Raja Bahroz`s mosque, now obscured by a modern veranda, had adhered closely to the form of contemporary mosques in Bihar Sharif. Due to the exceeding sanctity held by Bihar Sharif, those mosques doubtless were known to the converted Kharagpur family. Yet, as if to outshine the mosques of this esteemed city and architecture in Bihar during Shah Jahan`s patronage, Raja Bahroz`s instance is even more elegantly ornamented than the ones that serve as its models. Its polychromed stucco relief is more bountiful and copious than the ornamentation of any other contemporary Mughal structure in eastern India.

The tomb of Malik Wisal in Bihar is a simple and humble structure, consisting of a walled rectangular enclosure entered on the north. In the centre of this open courtyard is a raised platform upon which there lies seven graves. A stone-faced wall mosque, punctuated by three mihrabs is attached to its western end. Just outside the tomb can be witnessed a massive step well, rare so far east in India - a sudden dissimilarity in architectural pattern in Bihar under Shah Jahan, a man known to possess capabilities to godlike extent. Since Mughal authorities commonly were transferred from one part of the realm to another, they had indeed served as vehicles for the movement not only of style, but also, as in this case, whole new forms.