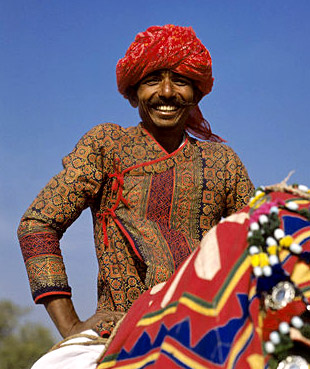

The angarkha is a part of the traditional male collection and is worn by almost all communities in Rajasthan. While the angarkha is the longer version, the shorter angarkhi is cut in a similar style.

The angarkha is a part of the traditional male collection and is worn by almost all communities in Rajasthan. While the angarkha is the longer version, the shorter angarkhi is cut in a similar style.

The angarkha is actually the formal wear of the affluent class in Rajasthan. Rajasthan`s pastoral and tribal communities may also wear the angarkha on particular occasions, however, for day-to-day activities, men usually wear the shorter version known as the angarkhi that is also known as the puthia in the region. Styles and lengths vary from region to region but the basic cut of this garment remains the same. The unique design element of an angarkha is the round-edged, sametime, triangular opening at the front and the inner panel known as the parda, which covers the chest and is visible through the cut out portion of the yoke. Some angarkha are made like a paneled coat while others are tailored by joining the bodice and skirt at the waist-although traditionally there was no seam at the waist. The fullness of the skirt varies, and does the size and shape of the garment. To improve mobility of the wearer, slits are occasionally made at the sides and also at the wrists. The angarkha is usually fastened at the neck, underarm, chest and waist with fabric ties or cords. It is interesting to note that in the Muslim tradition, the visible outer tie cords are positioned under the right armpit, while the Hindu angarkha have the noticeable ties under the left armpit. The inner fastenings are on the opposite side. In fact in Rajasthan and other parts of the country this style of tying still distinguishes the two communities.

Conventionally, the angarkha is made of plain silk or brocade, especially for wedding occassions. Fine cotton voile is also used and block printed cotton, with gold tinsel printing makes for a more dramatic angarkha. There are some impressive examples of elegantly tailored and handsomely embellished angarkha that are on display in Rajasthan museums. Angarkha made of thick and, sometimes, quilted materials are worn in winter while fine cotton is obviously preferred during the summers. At many Rajasthani courts and in other parts of Northern India the popularity of angarkha as a garment for formal wear continued into the nineteenth century. Its length and flare swayed to the dictates of fashion and varied over periods of time but its essential shape has survived unaltered.

The angarkhi or puthia features the same cut but is worn short, reaching just below the hips. It is made using white handspun cotton, reza and is usually coloured with vegetable dyes. In some communities the garment is made from red tul. The basic angarkhi worn among different communities displays a cut and construction that is very similar to the puthia described in the section on women`s costume. The front of the angarkhi consists of a right and left side with multiple panels, which extend beyond. Angarkhis often have a front circular yoke that is highlighted by piping. It has two front panels-right and left. These panels are separated into three sections-the right panel has one central piece, one on the side and the third is attached at the front from below the waist. The front left has one central panel, one at the side panel and the third runs from top to bottom. Often, the back or the sleeves of the angarkhi are heavily embroidered.

In Rajasthan, even common people were said to wear a relatively light garment whenever they were expected to be formally dressed. It was called a kamari or kamari angarkhi meaning-that which reaches the waist. As mentioned before, the basic cut of the angarkhi is general among all the communities of Rajasthan but differences are seen in the length and flare of the garment, the type of fabric and piping used as well as the usage or absence of colour.

The length of the angarkha can vary from 5-7.5 cm. below the waist down to the ankles. The Gaduliya Lohar`s angarkhi is waist-length and its full sleeves have 5 cm. wristbands cut on the bias with no slits. The Gujar`s angarkhi ends and reaches the hipbone. The Jat angarkhi falls just a little below his waist and the Meravat wears a long angarkhi.

Thus, the style of the garment seems to be mainly prejudiced by the wearer`s social status, the type of work the community does and the circumstance on which it is worn. The Rajputs, who were chiefly landowners and, therefore, wealthy enough to afford quantities of fabric, preferred a flared, ankle-length garment. Similarly, the trading communities such as Maheshvari, Osval and Agarval, who were thought to be of a high status in the society, wore a knee-length angarkha that was made of soft cotton khaadi. Significantly, Rajasthani people who were traditionally involved in more sedentary work would wear a garment like this at all times. A farmer, on the other hand, would reasonably wear a shorter, close fitting attire.