The study of history of Indian coins is both motivating and fascinating. India had served as a steaming pot of umpteen cultures since primeval times, witnessing countless invasions and onslaughts by rulers of other regions of the world. Since prehistoric times, India was always perceived as a land of bounty and colossal wealth. Thus, the country had veered the attention of some of the world`s most celebrated rulers like Alexander, the Huns and the Islamic rulers. It is indeed a complex situation to know today precisely from where the concept of coinage first evolved. But, based upon available evidences, it appears that the concept of `money` (as coins, which by definition here would entail a piece of metal of determined weight embossed with symbol of authority for financial transaction), was conceived by three different civilisations independently and almost at once. The ancient coins were introduced as a means to trade things of daily usage in Asia Minor, India and China in 6th century B.C. There were various types of coins in ancient India each depicting the times of their existence and the eras.

The study of history of Indian coins is both motivating and fascinating. India had served as a steaming pot of umpteen cultures since primeval times, witnessing countless invasions and onslaughts by rulers of other regions of the world. Since prehistoric times, India was always perceived as a land of bounty and colossal wealth. Thus, the country had veered the attention of some of the world`s most celebrated rulers like Alexander, the Huns and the Islamic rulers. It is indeed a complex situation to know today precisely from where the concept of coinage first evolved. But, based upon available evidences, it appears that the concept of `money` (as coins, which by definition here would entail a piece of metal of determined weight embossed with symbol of authority for financial transaction), was conceived by three different civilisations independently and almost at once. The ancient coins were introduced as a means to trade things of daily usage in Asia Minor, India and China in 6th century B.C. There were various types of coins in ancient India each depicting the times of their existence and the eras.

However, even prior to the advent of the first ever cast and moulded ancient coins of India, there existed different sort of economical transaction, which is verily regarded as the precursor of coin-making. It is understood that self-subsistent economy was very much prevalent in ancient India, during the Pre-Vedic era. A family would generally cultivate and produce what was required for them. Step by step, these small families came together to establish small communities or tribal clans. That was when the needs of people were upgraded from the `self subsistence economy` to `barter economy`, where goods were switched between people or amongst various communities. People began to comprehend the limitations of the barter system economy, primarily because two commodities were never of the matching value. Particular affairs got preference over the others and a higher value was attached to them. This ensued in differences between parties or most often, there was no equal benefit of business interest to one of the parties due to the transaction.

That was also when the want for a `common commodity` as a medium of exchange arose and they are precisely considered as the harbingers of ancient coins in India. The mammoth granaries discovered at the Mohenjo Daro and Harappa excavation sites substantiate to the fact that agricultural products were used as authentic medium of exchange. The Vedic people used cows as a medium of exchange and this is very much apparent from several ancient literary sources like the Aitreya Brahmana, the Rig Veda and the Ashtadhyayi. One passage in the Rig Veda mentions the price of the image of Lord Indra`s idol was offered on sale in exchange of ten cows! Similarly, in the Aitreya Brahmana, there is an allusion to the number of cows as an evaluation of wealth. Cows had remained as a dependable medium of exchange till the later part of the post-Vedic period. This is evident from specific passages of Ashtadhyayi of Panini. Cows conformed to the needs of the age, as they were not easily perishable, could be moved from one place to another and had the capacity to reproduce, work and supply milk. However, cows were a bothersome medium of exchange, as they demanded to be cared for and some degree of skill in rearing. Hence, this medium was highly inappropriate for large transactions and long-term savings etc.

During Rig-Vedic period, tiny kingdoms had begun to come to existence all over the Indian subcontinent from Kabul (Kubha in Sanskrit) to upper Ganges. Most of these were the small states under hereditary monarchs and few republics. These small and large states were referred to as Janapadas and Mahajanpadas. Approximately in 6th century B.C., sixteen Mahajanapadas or realms rose to pre-eminence in India. According to the ancient text Anguttara Nikayas (a Buddhist scripture, the fourth of the five nikayas, or compendiums in the Sutta Pitaka) these Mahajanapadas were - Anga, Magadha, Kashi, Koshala, Vajji, Malla, Vatsa, Chedi, Kuru, Panchala, Matsya, Surasena, Ashvaka, Avanti, Gandhar and Kamboja. One of the most ancient coins of India was minted by one of these mentioned realms. Each of the kingdoms had issued distinctive type of silver coins to facilitate commercial traffic.

Approximately during 600 B.C., in north-western part of India, Takshashila or Taxila and Pushkalavati, became significant commercial centres for trade and commerce with Mesopotamia. These wealthy satraps (provinces) had ushered in a unique coinage to facilitate the trade. The collection comprised silver concave bars of 11 grams, which are popularly called as `Taxila bent bars` or `Satamana bent bars`. Satmana or Shatamana corresponded to 100 rattis of silver in weight (Shata means 100 while mana means unit). These silver bars were perforated with two septa-radiate (seven arms) symbols, one at each end. These bent bars do truly symbolise one of the oldest and ancient coins of India. Ancient Indian coinage was based upon `Karshapana` unit that consisted of 32 rattis (3.3 grams of silver). A `Ratti` is equivalent to 0.11 grams, which is the average weight of a Gunja seed (a brilliant scarlet coloured seed). Auxiliary denominations of Karshapana, like half Karshapana (16 ratti), quarter Karshapana (8 ratti) and 1/8 of Karshapana (4 ratti) were also minted.

In ancient India, precisely during 600-321 B.C., several Janapadas had issued coins with only one symbol like Lion (Shursena of Braj), humped bull (Saurashtra) or Swastika (Dakshin Panchala). Four symbol coins were issued by Kashi, Chedi (Bundelkhand), Vanga (Bengal) and Prachya (Tripura) Janapadas. However, five symbol punch marked coins were first issued by Magadha, which were continued during the subsequent Mauryan expansion. Ajatashatru (legendary ruler of Magadha Empire, son of Bimbisara) was followed by numerous kings, who eventually lost this kingdom to the family of the Nandas. To maintain the colossal army of 200,000 infantry and 3000 elephants, (supported by Greek evidence), the Nandas had to resort to heavy taxation which was detested by people. They found their new leader in Chandragupta Maurya (321-297 B.C.) who eventually with the help of Taxilian Bramhin Kautilya or Chankya overthrew the Nanda ruler and laid the foundation of the illustrious dynasty of Maurya.

Ashoka was the last emperor of the Mauryan Dynasty, which to decline soon after his death. Numerous kingdoms arose out of ruins from this great empire. Northern India was divided into many republics which were controlled by various ganas (tribes) like Achuyta, Ahicchatra, Arjunayana, Ayodhya, Eran, Kaushambi, Kuninda etc. The highly ancient Indian coins issued by these republics/kingdoms are occupying both historically and numismatically. Kuninda, referred to as Kulinda in ancient literature, issued very attractive silver coinage during the late 2nd century B.C. These ancient coins were in fact issued by king Amoghbhuti, who had ruled in the fertile valley of Yamuna, Beas and Sutlej rivers (modern day Punjab in northern India). The obverse of the coins depicts a deer and goddess Lakshmi holding a lotus in her lifted hand. Between the horns of the deer, a cobra symbol is also portrayed. The reverse further delineates 6 symbols, comprising a hill and river below, Nandipada (hoof of bull), a tree in railing, Swastik and a `Y` shaped symbol. Captivatingly, these Kuninda coins from ancient India were pretty much bilingual. On the obverse, legends were embossed in Prakrit, penned in Brahmi script, whereas, the reverse was done in Kharoshti. The legends on the obverse read Rajnah Kunindasya Amoghabhutisya maharajasya. The reverse carries Maharajasa in Kharoshti script at the same place where Indo-Greece and Saka coins delineated their ruler`s names.

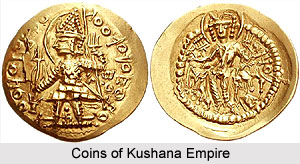

These very ancient coins from India exemplify the first ever effort of an Indian ruler to issue silver coinage, which could compete in commercial issues with that of Indo-Greek coinage. Indo-Greek kings who ruled in neighbouring areas (Bactria and Punjab) had begun issuing splendid illustrations of silver coins which, were highly sought after. This made Amoghbhuti to introduce coins of purely Indian design, but of outstanding loveliness to certify economic pre-eminence over his neighbours. The Kuninda kingdom was eventually invaded by Kushan and Shakas in middle of first century B.C. Both, Indo-Greek and Kuninda kingdoms were annexed to make the next great empire of India, the Kushana Empire.

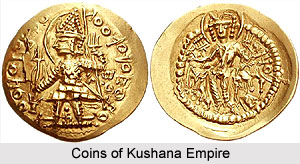

The coins of Kushana Empire reveal a great deal about the rulers of that time. Undoubtedly, all the Kushana coins were used as a media to propagate the Kings superiority. The concept of showing king or the ruler on the coins was non-existent in India and all the previous dynasties minted coins showing only the symbols (called as the punch marked coins). It was the Kushana rulers who popularized this idea, which remained in use for another 2000 years. Kushana coinage was copied not only by later Indian dynasties like the Guptas, but also by the neighbouring kings like Sassanians (of Persia).