The four months, specifically June, July, August and September form the nucleus of the rainy season, virtually all over the country. The length of the rainy season, however, goes on lessening from south to north and from east to west. In the extreme north-west it scantily pours for two months. Between three-fourths and nine-tenths of the total rainfall is concentrated over this period. This might furnish an idea of how unequally it is circularised over the year.

The low-pressure conditions over the northwestern plains further gets more strengthened. By early June they are controlling enough to draw in the trade winds of Southern Hemisphere. These south-east trade winds basically originate in the oceans. Travelling from the Indian Ocean, they traverse the equator and enter the Bay of Bengal and Arabian Sea, only to be hit by the air circulation over India. Crossing over the equatorial warm currents, they transport with them abundant moisture. After voyaging over the equator, they adopt a south-westerly direction. This is why they are known as south-west monsoons. Therefore, the north-east trades of winter, initiating on the land, are swapped by absolutely opposite south-west monsoons, saturated with moisture. The monsoons, unlike the trades are not stable winds. They are fundamentally quivering in nature.

The rain-bearing winds are tough. They blow at an average speed of 30 km per hour. Excluding the tremendous north-west, they flood the country in a month`s time. The abrupt approach of the moisture-laden winds is connected with awful thunder and lightning. This is known as "break" or "burst" of the monsoons.

It is of exceeding significance to observe that these monsoon winds take a south-westerly pathway. But as they advance towards the land, their course is altered by the relief and thermal low pressure over northwest India. In the first place, the Indian Peninsula separates the monsoons into two branches. They comprise the Arabian Sea branch and the Bay of Bengal branch.

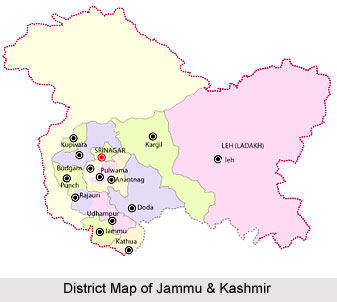

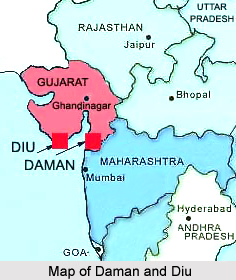

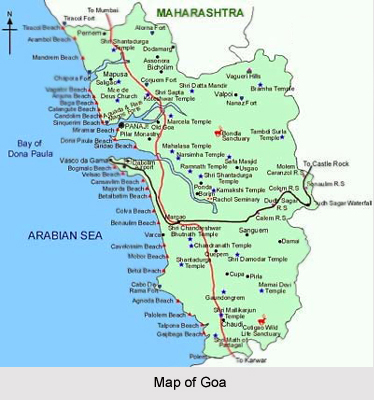

The Arabian Sea branch of the monsoons is blockaded by Western Ghats. The weather side of the Sahyadris get much more heavy rainfall. Traversing the Ghats, they invade the Deccan plateau and Madhya Pradesh, causing a reasonable amount of rainfall. Subsequently they enter the Ganga Plains and merge with the Bay of Bengal branch. Another part of the Arabian Sea branch hits the Saurashtra peninsula and Kach. It then crosses over into west Rajasthan and along the Aravallis, causing only insufficient rainfall. In Punjab and Haryana, it too unites with the Bay of Bengal branch. These two branches, strengthened by each other, induce rains in the Western Himalayas.

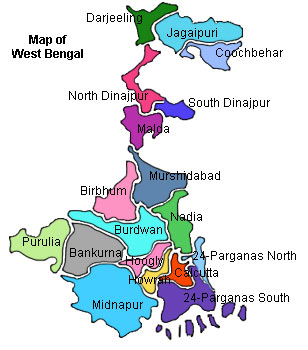

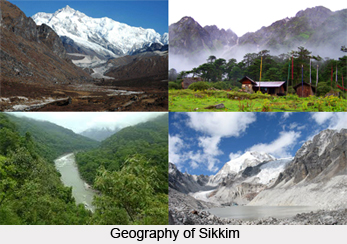

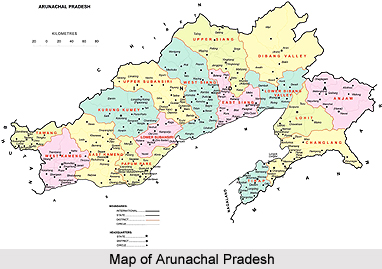

The Bay of Bengal branch is by nature headed towards the coast of Myanmar and part of south-east Bangladesh. But the Arakan Hills, along the coast of Myanmar are good enough to redirect a big portion of this branch, permitting it to enter the Indian subcontinent. The monsoon thus enters West Bengal and Bangladesh from south and south-east, instead of the south westerly pathway. Afterward this branch divides into two, under the authority of the impressive Himalayas and the thermal low in North west India. One branch travels westward along the Ganga plains, reaching as far as the Punjab plains. The other branch moves up the Brahmaputra valley in the north and northeast, causing extensive rainfall in Northeastern India. Its sub-branch hits the Garo and Khasi Hills of Meghalaya. Mawsynram, located on the summit of the southern range of Khasi Hills, gets the highest average yearly rainfall in the world. Cherrapunji, located 16 km east of Mawsynram, holds some other rainfall records.

Distribution of rainfall received from southwest monsoons is mostly administered by the relief or orography. For example, the weather side of the Western Ghats catalogues a rainfall of over 250 centimetres. In contrast, the leeward side of these Ghats is barely able to receive even 50 centimetres. Then again, heavy rainfall in the north-eastern states can be assigned to their hilly ranges and Eastern Himalayas. Rainfall in the Northern Plains goes on lessening from east to west. During this particular season

Kolkata receives approximately 120 centimetres, Patna 102 cm, Allahabad 91 cm and Delhi 56 cm.

The monsoon rains take place in wet spells of few days duration at a time. The wet spells are scattered with rainless intervals. This wavering nature of monsoon is accredited to the cyclonic depressions, primarily shaped at the head of Bay of Bengal, and then traversing into the mainland. Besides the regularity and concentration of these depressions, the path followed by them ascertains the spatial circulation of rainfall. The path is at all times along the axis of the "monsoon trough of the low pressure". For several reasons the trough and its axis keep on travelling northward or southward. For the Northern Plains to receive a reasonable amount of rainfall, it is essential that the axis of the monsoon trough should lie in the plains for the most part. Then again, every time the axis shifts close to the Himalayas, there are extended dry spells in the plains, and extensive rains in the mountainous basins of the Himalayan Rivers. These heavy rains bring in ravaging floods, causing immense injury to life and land in the plains.

The monsoons are well-known for their inexplicable changes and uncertainties. The vacillation of dry and wet spells keep on altering in concentration, regularity and in continuance. On one hand, if they induce heavy floods in one part, they may be liable for droughts in the other. They are often found unbalanced and belated in their arrival, as well as in their retreat, disrupting the whole farming schedule of the millions of farmers.