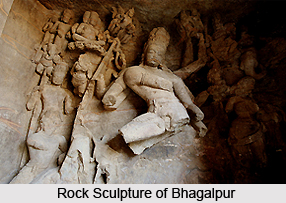

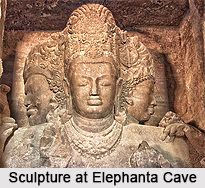

Sculpture of Hindu caves of Post Gupta Period point towards some loose sculpture, generally fragmental, believed to have come from Elephanta, and is intimately linked to the dominating style in northern Gujarat, in 6th and 7th centuries. However, the great bas-relief at Parel of Lord Shiva, manifolding himself, shares both the style and the character of metaphysical perception of the great image at Elephanta.

Sculpture of Hindu caves of Post Gupta Period point towards some loose sculpture, generally fragmental, believed to have come from Elephanta, and is intimately linked to the dominating style in northern Gujarat, in 6th and 7th centuries. However, the great bas-relief at Parel of Lord Shiva, manifolding himself, shares both the style and the character of metaphysical perception of the great image at Elephanta.

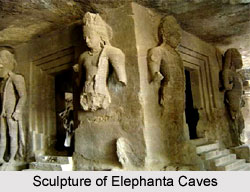

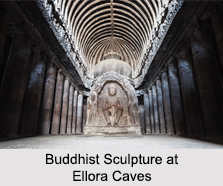

The most significant of all the rock-cut sites of the second phase is Ellora near Aurangabad, now in Maharashtra. Here, in the western face of a protrusion of the Sahyadri Hills, some 35 caves and rock-cut temples, Hindu, Buddhist and Jain, stretch for three-quarters of a mile. One of the earliest, presumably of the mid-6th century, is the Hindu Ramesvara (Cave 21) with a well-adjusted plan, the enhancement of an inner sanctum with a circumferring passage, and a Nandi on a high platform, facing the access wall, all just as in a structural temple. On the parapet wall between the exterior pillars of the hall are exquisite relief friezes of elephants and mithuna couples, and there are brackets in the shape of salabhaiijikas. Inside, antechambers with two-column porches open on both sides, their walls sculptured, like in Elephanta, with images of the gods and vistas from Pauranic legends. Relief figurines on both sides of the entryways to the sanctum include a Durga vanquishing the demon buffalo and- possibly the best- a dancing Shiva, both knees bent (kfipta) and body facing the onlooker in a way distinctive of Indian dance throughout ages. Less valiant in size and posture than the Nataraja in Elephanta, but far healthily preserved, the god is intuition with an over the top rhythm, emphasised by the fall of his jata (crown of matted locks) in disorder on to his right shoulder. The musicians flocking, nearly herding around, of an extraordinary exquisiteness and individualism and on a corresponding scale, gives a feel almost of the genre to the scene. The Seven Mothers seated in a row in the same antechamber have an equivalent appeal of aspect and identity of posture. Outside, engraved into the rock face at every end of the veranda, are the river-goddesses, in a more conservative post-Gupta style.

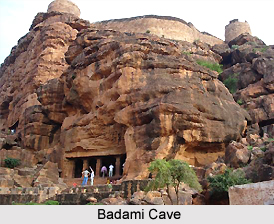

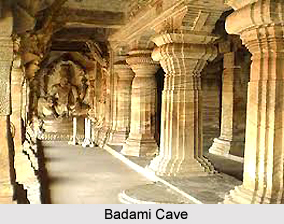

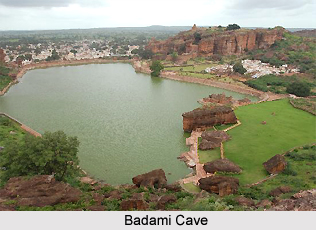

Permitting the dissimilar arrangement of the cliff, the so-called Dhumar Lena (Cave 29) nearly replicates the Elephanta Cave in design, iconography and ample scale, and was plausibly stimulated by it. There is even a similar seated Lakulisa image dacing a Nataraja. Though the sculpture is of inestimably substandard quality, much of it incomplete, the resemblance to Elephanta demands a connection between the early Hindu caves at Ellora and the Kalachuris, who must have been past their heyday by the end of 6th century, when they endured a crush at the hands of the early western Chalukya sovereign, at whose capital in northern Karnataka- Badami- Cave 3, dated by inscription to 578 A.D., shares with the Ramesvara at Ellora, the prominent attribute of human couples as brackets. The Hindu caves in Ellora, elite to the Rashtrakuta ones, thus surely belong to the second half of 6th century.

Permitting the dissimilar arrangement of the cliff, the so-called Dhumar Lena (Cave 29) nearly replicates the Elephanta Cave in design, iconography and ample scale, and was plausibly stimulated by it. There is even a similar seated Lakulisa image dacing a Nataraja. Though the sculpture is of inestimably substandard quality, much of it incomplete, the resemblance to Elephanta demands a connection between the early Hindu caves at Ellora and the Kalachuris, who must have been past their heyday by the end of 6th century, when they endured a crush at the hands of the early western Chalukya sovereign, at whose capital in northern Karnataka- Badami- Cave 3, dated by inscription to 578 A.D., shares with the Ramesvara at Ellora, the prominent attribute of human couples as brackets. The Hindu caves in Ellora, elite to the Rashtrakuta ones, thus surely belong to the second half of 6th century.

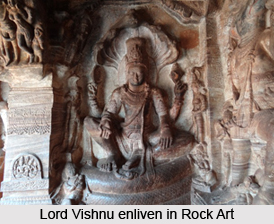

The Hindu Caves, chiselled out of red sandstone, cliffs of Badami are all Vaishnava, with one Jain exception, and of humble size. The most detailed, Cave III, possesses a simpler plan compared to Ramesvara in Ellora, without antechambers, and the sanctum is but a miniature square cell, excavated out of the back wall. The sculptures include Vishnu as a boar (Varaha), as a lion (Narasimha), and repeated in each of the Hindu caves, as Trivikrama in the Vamana (dwarf) embodiment. The statuettes tend to be self-assertive, nearly savage, generally standing stiffly in samapada, with expanded legs and over-sized hands. The gods` jewellery, on the other hand, is furnished with immense daintiness. The compositions are deficient in atmospheric appeal like the panels in the Kalachuri caves, though some of the attendee figurines are often excellent grotesques in the purest Gupta style. Quality however, always is variable. The seated Vishnu at one end of the hall is a mighty menacing presence, the Narasimha at the other end an engrossing statuette. Though humble and elementary in design, the Badami caves emote a feeling of lavishness because of the delicate carving of minor figurines and ornamental motifs, especially on the ceilings.

The Hindu Caves, chiselled out of red sandstone, cliffs of Badami are all Vaishnava, with one Jain exception, and of humble size. The most detailed, Cave III, possesses a simpler plan compared to Ramesvara in Ellora, without antechambers, and the sanctum is but a miniature square cell, excavated out of the back wall. The sculptures include Vishnu as a boar (Varaha), as a lion (Narasimha), and repeated in each of the Hindu caves, as Trivikrama in the Vamana (dwarf) embodiment. The statuettes tend to be self-assertive, nearly savage, generally standing stiffly in samapada, with expanded legs and over-sized hands. The gods` jewellery, on the other hand, is furnished with immense daintiness. The compositions are deficient in atmospheric appeal like the panels in the Kalachuri caves, though some of the attendee figurines are often excellent grotesques in the purest Gupta style. Quality however, always is variable. The seated Vishnu at one end of the hall is a mighty menacing presence, the Narasimha at the other end an engrossing statuette. Though humble and elementary in design, the Badami caves emote a feeling of lavishness because of the delicate carving of minor figurines and ornamental motifs, especially on the ceilings.

The two Aihole caves, Hindu and Jain, are also brilliantly embellished from inside. The Ravanaphadi sports a more evolved design, with a much bigger sanctum, resonant of the Ramesvara at Ellora. It too is `Saiva` (adjective of Shiva), with an excellent dancing Shiva flanked by dancing Matrakas in one of the antechambers (the other unfinished) and, on both sides of the passageway into the sanctum, Durga Mahisasuramardini and a Varaha. The sculptures are vastly individualistic, quite discrete from those of Ellora as well as the Badami caves. Farther from the Gupta idiom, the figurines are gifted with a gentle refinement, the legs are trim and delicately done, the crowns exceedingly soaring, and clothing is fanatically indicated by means of profoundly parallel panels. Outside the entryway, all but obscured, is a pair of doormen in `Scythian` attire, an astoundingly late survival of a custom of foreign guards, first referred to by Megasthenes.

Undeniably later, though hard to date, is the Rava-ka-Khai (no.14) at Ellora, placed as it is between the most sophisticated of the Buddhist caves (no.12) and the Dasavatara (no.15), unquestionably Rashtrakuta in style. The Rava-ka-Khai has an exceptionally rational, thoroughly hinduised plan, with ample space for circumferring and a colonnaded hall, antecedent of the sanctum. On each sidewall, differentiated by ornate pilasters, are five panels- Saiva on the left, Vaishnava on the right. The rectangular garbhagriha (sanctum sanctorum) suggests that this cave was definitely dedicated to a female divinity or divinities.

Undeniably later, though hard to date, is the Rava-ka-Khai (no.14) at Ellora, placed as it is between the most sophisticated of the Buddhist caves (no.12) and the Dasavatara (no.15), unquestionably Rashtrakuta in style. The Rava-ka-Khai has an exceptionally rational, thoroughly hinduised plan, with ample space for circumferring and a colonnaded hall, antecedent of the sanctum. On each sidewall, differentiated by ornate pilasters, are five panels- Saiva on the left, Vaishnava on the right. The rectangular garbhagriha (sanctum sanctorum) suggests that this cave was definitely dedicated to a female divinity or divinities.

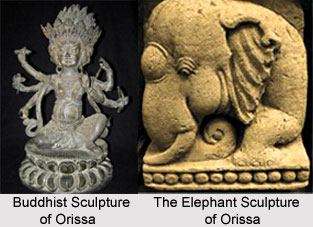

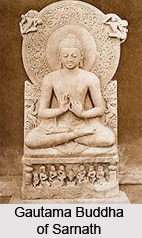

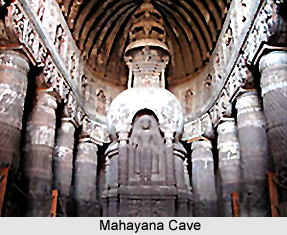

Approximately contemporary with the Hindu caves in Ellora are the second-phase Mahayana caves in Aurangabad. One group (1 & 3), looks to continue the finest Ajanta works; Cave 3 especially, corresponds more or less closely in design, and the carving of some of the pillars indeed excels anything in Ajanta. The second group (caves 2,5,6,7,8, and 9) merges Hindu-type sanctums in the centre of what used to be the hall (own with a porticoed entryway) with cells cut into the side and back walls and (Cave 7) a columned veranda of Buddhist kind. The hardness and deficiency of novelty and ingenuity in the carving of the pillars and pilasters cheat on the later date. On the other hand, nowhere is the litany of Avalokiteshwara more resplendently exemplified, and the goddesses, without question Tara with an attendee, standing on each side of the sanctum door are among the finest 6th century and 7th century cave sculptures in Maharashtra. The dancing woman with flanking female musicians on one wall of the inner sanctum is unequalled in the whole corpus of Indian sculpture. Most of the Buddhas in these caves are seated in European mode.