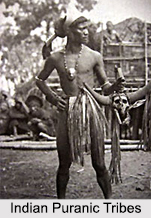

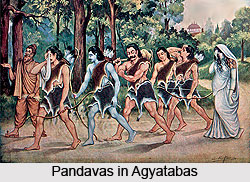

Agyatabas of the Pandavas have received prominence in the epic of Mahabharata. The forest residence of the Pandavas and especially of Draupadi has far richer significance for the Draupadi cult. In fact it can be said that as to the Mahabharata`s forest episodes, those that concern Draupadi are for the most part well known within the Draupadi cult. It has been said that during their stay in the forest Draupadi and the Pandavas must conceal their identities. The Terukkuttu drama cycle almost uniformly presents enactments of the period that the Pandavas and Draupadi spend incognito in the kingdom of Virata.

Agyatabas of the Pandavas have received prominence in the epic of Mahabharata. The forest residence of the Pandavas and especially of Draupadi has far richer significance for the Draupadi cult. In fact it can be said that as to the Mahabharata`s forest episodes, those that concern Draupadi are for the most part well known within the Draupadi cult. It has been said that during their stay in the forest Draupadi and the Pandavas must conceal their identities. The Terukkuttu drama cycle almost uniformly presents enactments of the period that the Pandavas and Draupadi spend incognito in the kingdom of Virata.

It has been said that before they enter Virata`s kingdom, the Pandavas conceal their weapons in a vanni tree, and Dharma worships the goddess Kalikaparamecuvari, asking her to protect the weapons until the Pandavas return for them.

In a burlesque scene, the Pandavas then come before Virata one at a time in their various disguises. The last to arrive, more sombre than her predecessors, is Draupadi. Of the disguises, special mention must be made of Arjuna and Draupadi.

Arjuna had taken the disguise of a eunuch. Eunuch Arjuna is portrayed here as an evocation of Lord Shiva Ardhanariswara. Draupadi enters with her hair loose delivering a song in soliloquy that reveals that she is Amman-Panchali, born from red fire, the chaste and very beautiful sister of Lord Krishna whose colour is like the black clouds. Draupadi`s disguise thus portends the war to come, which cannot be ended until her own hair will be dressed in the scene that closes the Terukkuttu cycle with red or orange flowers. The flowers provide ritual accentuation of a link that is already implied in the classical epic between Draupadi`s dishevelment and her disguise as a hair-dresser-Sairandhri.

It is striking that this drama on the disguises accentuates transvestism in connection with both Arjuna and Bhima. In the former case, it evokes the bisexual Shiva, the form in which Shiva and Shakti, purusa and prakrti, are merged into one.

Draupadi goes well beyond her traditional epic role to provide a concentration point for a culturally enriched mythology of the Hindu goddess, the disguised Draupadi of the Virataparvan remains much closer to the classical epic prototypes and unveils dimensions of the goddess that are in the main already implied in the traditional epic story. Furthermore, whereas in the first setting Draupadi`s violent-heroic character is quite explicit, in the second it is only implicit and must be read through the play of the symbols.