The ancient Hindu medicine dates back to the prehistoric time and it is as old as the civilisation is. The rudiments of ancient medicine started from Vedic period and in the there are mentions of medicinal plants and herbs. The introduction of Ayurveda in earth was made by Lord Brahma when he saw the suffering of human beings.

The ancient Hindu medicine dates back to the prehistoric time and it is as old as the civilisation is. The rudiments of ancient medicine started from Vedic period and in the there are mentions of medicinal plants and herbs. The introduction of Ayurveda in earth was made by Lord Brahma when he saw the suffering of human beings.

Archaic Hindu medicine in its earliest context is to be found mostly in the hymns of the Atharva Veda, and the Vedic term `bheshaja`, used to denote medicinal charms, which occurs also in the Avesta as baesaza or baesazya, suggests a common Aryan origin. It is a `psychosomatic` approach to healing, part of a philosophical system. It is a scheme in which the lay physician and the priest perform their respective roles in controlling the ills of the body and of the soul. Native pre-Aryan tradition and practice were imbibed. Mohenjodaro, which had the finest public health facilities in the ancient East, could boast bathrooms and a drainage system, and no doubt influenced personal hygiene. The deity Dhanvantari, custodian of the elixir of immortality, became the fount of wisdom for virility and duration in life (ayurveda) and the remedies (bhaishajya) to ensure these. He figures in Susruta as the divine authority in medicine.

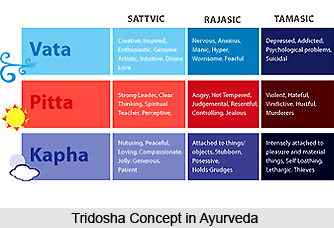

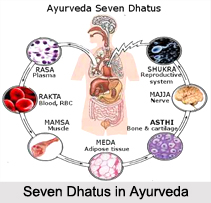

The theoretical basis of ancient Hindu medicine was metaphysical and was restricted by tradition and by isolation from other sciences. In the practice of ancient Hindu medicines, diseases like fever was considered as a demon, offspring of indigestion, the commonest cause of illness. According to ancient Indian scriptures, the human body was maintained in a state of health by the three humours, phlegm, gall, and wind (or breath) in their correct proportions. These proportions could be achieved by proper diet, an important consideration in a trying climate. The humours were forms of the life-energy and corresponded to divine forces or agents in the macrocosm, i.e. outside the body; thus phlegm, cool and heavy, which resided in the chest and lungs, was associated with the moon. Hindu interpretation gave wind prime significance among the humours, since it appeared to govern the dynamics of the body; from the pre-Aryan Yoga to the Vedanta philosophy there developed a theory of winds (vayu) or manifestations of the life-breath.

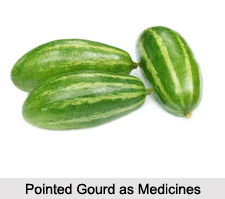

As per the ancient Hindu medicine, disregard of proper diet leads to a disturbance of the balance of the humours. These become incensed, and overflowing their normal channels invade the domain of others, thereby causing disease. The basis of dietetics and pharmacology was the Hindu theory of the six essences (rasa), which appear to correspond to the Greek glyky, liparon, stryphnon, halmyron, pikrofl, and drimy. Tradition had established an elaborate doctrine of correspondence between the essences (qualities or flavours) in certain foods and the specific substances in the humours. A vast pharmacopoeia enshrined traditional remedies.

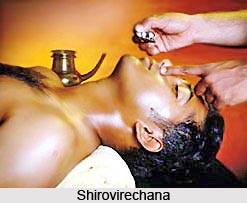

The tradition of ancient Hindu medicines indicates the implementation of certain remedial methods. In the ancient Hindu medicines, the treatment of the patient an all-powerful `arcanum` was blended from various herbs, each contributing specific healing properties. These material properties were reinforced by supernatural powers invoked by the Brahman practitioner who claimed a special relationship with the twin horsemen and divine physicians, the Asvins. Honey possessed unusual healing virtues, being associated with amrita, the elixir of immortality.

Another significant feature of Hindu medicine was the absence of any attempt to recognize diseases of the brain. One would not have expected much progress in this study in ancient times in any case, but the reason for such neglect is to be found in the assumption that the centre of consciousness, thought, and feeling is the heart, a generalization which is implicit also in the writings of Homer. Caraka certainly mentions insanity, but it is covered by the general explanation of the overflowing of `incensed elements`, in this instance into the special vessels carrying the `mind-stuff`, or by the entry of demons.

Among the diseases mentioned in Vedic medical texts are diarrhoea (asrava) , fever (takmari) , dropsy (jalodara), consumption (balasa, yakshma), tumour (akshata), abscess (viaradha), leprosy and certain skin diseases (kilasa), and congenital diseases (kshetriya). Dropsy was sent by Yaruna, the god of the primal waters. Jaundice, for which Caraka later records diagnosis and treatment, is characterized by the presence of the demon who causes yellowness (hariman).

On pursuing inquiry to the borders of the realm of legend the historian gleans one indisputable fact, namely, that the fount of ancient Hindu medical wisdom was the oral teaching of Punarvasu Atreya. According to the Buddhist Jatakas a physician Atreya taught at Takshasila (Taxila) in the age of Lord Budha. It appears that six pupils of Atreya first set down this wisdom in encyclopedic form, but of these versions only two, those of Bhela and Agnivesa, have survived. A defective manuscript of Bhela Samhita, discovered in south India, reveals the same tradition as is to be found more fully expounded in the Charaka Samhita, which is the final form of the compilation of Agnivesa and is our best source of Hindu medical knowledge as it existed in the last few centuries B.C. Caraka is generally believed to have been the court physician to King Kanishka at Peshawar in the first or second century A.D.

Ayurveda as set forth in Charaka makes no mention of surgery, being solely the province of the physician. The development of surgery is initially attributed to the genius Susruta who may have taught and practiced in Kashi (Varanasi). He incorporated surgery into the general field of medicine and stressed the importance of surgery in the study of anatomy (which was the major weakness in Hindu medical knowledge). With Susruta also there ended the specialized tradition of elephant medicine.

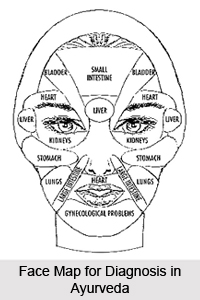

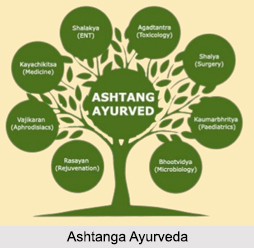

The tradition of ancient Hindu medicine made an eight-part division of the field of study, broadly in respect of (a) Diseases, their diagnosis and treatment, and (b) The means of healing in relation to the whole man, the philosophical and ethical approach. In this respect, under the study of diseases, their diagnosis and treatment, the illnesses requiring surgery (salya) and the science of obstetrics are found.

Moreover, diseases of the eye, ear, nose, and throat (salakya); diseases due to the disturbance of the humours which involve the therapy of the whole organism; mental and other disturbances of demoniacal origin; pediatrics, i.e. children`s diseases, caused by demons; and finally, three aspects of ayurveda, medicinal drugs (agada) and antidotes, elixirs of life (rasayana), and virility (vajikarana) are also detected by the help of the study. With the study of the means of healing, the organism or `sarira` is considered including its moral and physical health (vritti), the origins of disease, and the nature of pain and illness in terms of the balance of the humours, treatment or action (karman), the consequences of treatment, the influence of time (kala) in respect of the age of the patient or perhaps the seasons, and lastly, the professional conduct of the agent or physician, his diagnosis, his methods and instruments (karana). Emphasis was laid upon the preventative aspect and early treatment.

Moreover, diseases of the eye, ear, nose, and throat (salakya); diseases due to the disturbance of the humours which involve the therapy of the whole organism; mental and other disturbances of demoniacal origin; pediatrics, i.e. children`s diseases, caused by demons; and finally, three aspects of ayurveda, medicinal drugs (agada) and antidotes, elixirs of life (rasayana), and virility (vajikarana) are also detected by the help of the study. With the study of the means of healing, the organism or `sarira` is considered including its moral and physical health (vritti), the origins of disease, and the nature of pain and illness in terms of the balance of the humours, treatment or action (karman), the consequences of treatment, the influence of time (kala) in respect of the age of the patient or perhaps the seasons, and lastly, the professional conduct of the agent or physician, his diagnosis, his methods and instruments (karana). Emphasis was laid upon the preventative aspect and early treatment.

In the history of the ancient Hindu medicine, there is no reference to hospitals, but they evolve with the spread of Buddhism. The Mauryan Emperor Ashoka celebrates the beginnings of social medicine, whilst Ceylon, by the fourth century A.D., could boast some hospitals, and a medical service. The Sangam literature of southern India serves as the evidence of the treatment of out-patients in dispensaries.