Allahabad, situated at the junction of the Ganga River and the Jamnah (present day Yamuna river), formed the armed gate through which alone reliefs from Calcutta could reach Kanhpur (Kanpur) and Lucknow (Lucknow). Should that gate be closed, or should it be occupied, the fate of both the places mentioned would have depended solely on the result of the operations before Delhi.

Allahabad, situated at the junction of the Ganga River and the Jamnah (present day Yamuna river), formed the armed gate through which alone reliefs from Calcutta could reach Kanhpur (Kanpur) and Lucknow (Lucknow). Should that gate be closed, or should it be occupied, the fate of both the places mentioned would have depended solely on the result of the operations before Delhi.

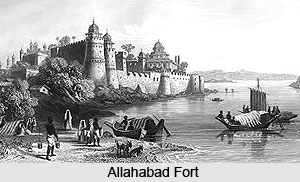

The fort of Allahabad, founded by Akbar in 1575, lies on a tongue of land formed by the convergence of the two great rivers - Ganga and Yamuna. It is 120 miles distant from Kanhpur, seventy-seven from Benaras, 564 by the railway route, and somewhat more by water from Calcutta. It touched the southern frontier of Oudh, and was in close proximity to the districts of Juanpur, Azamgarh, and Gorakhpur. The landowners in these places had been completely alienated from their British masters by the action of the land and revenue system introduced by Thomason.

The news of the revolt of Mirath and the seizure of Delhi reached Allahabad on the 12th of May. The force there was entirely native, the garrison consisting of the 6th Regiment N. I. and a battery of native artillery. Additions to this purely native force were made early during the month of May. On the 9th, a wing of the `Regiment of Firuzpur,` a Sikh regiment which had been raised on the following day of the campaign of 1846. On the 19th a squadron of the 3rd Oudh Irregular Horse, also natives, reached the place. The bulk of these troops occupied a cantonment about two and a half miles from the fort, to which they supplied weekly guards. The commanding officer was the Colonel of the 6th N. I., Colonel Simpson, a polished gentleman, but scarcely a born leader of men. The chief civil officers were Chester and Court, both men of ability.

These gentlemen had pointed out to the authorities in Calcutta the great danger of leaving a place so important as Allahabad entirely in the hands of natives. They received permission, in May, to secure from Chanar, a fortress on the Ganges, seventy-six miles distant, some of the European invalided soldiers permanently stationed there. Sixty-five of these arrived on the 23rd of May, and a few more some time later. They were at once placed within the fort.

One of the most remarkable features of the great unrest was the supreme confidence, which officers of the native army reposed to the very last in their own men. This confidence was not shaken when the regiments around them would rise in revolt. Every officer argued, and sincerely believed that, whatever other sipahis (soldiers) might do, the men of his regiment would remain true. This applied specially to the officers of the 6th N.I. To make their men comfortable, to see that all their wishes were attended to, had been the one thought of those officers. The men, by their behaviour, seemed to reciprocate the kindly feelings of their superiors.

When, then, regiments were rising all over India, the officers of the 6th boasted that, whatever might happen elsewhere, the 6th N. I. would remain unswerving and true. His conviction was so strong that when, on the 22nd of May, a council was held of the chief civil and military authorities, Colonel Simpson deliberately proposed that the whole of his regiment should be moved into the fort to hold it. Court most persistently, and ultimately successfully, opposed this proposal. The day following, the invalids arrived from Chanar. Then all the non-combatants of the station, those in the civil service excluded, moved into the fort with their property.

A circumstance occurred towards the end of May which seemed to justify the confidence of the officers of the 6th N. I. The. sipahis of the regiment, confessing the greatest indignation at the conduct of their brethren in the north-west, formally volunteered to march against Delhi. Their offer was telegraphed to Calcutta, and afforded ground to the councillors of Lord Canning to insist upon their disputation that the mutinous spirit was confined to but few stations.

About a week after the sipahis of the 6th had volunteered to march against the capital of the Mughals, they rose in revolt, and murdered many of their own trusting officers, and some young boys, newly-appointed ensigns, who happened to be dining at the regimental mess. In reply to the offer to volunteer, the Governor-General had thanked the regiment for its loyalty. A parade was ordered for the morning of the 6th of June to read the Vice-regal thanks to the sipahis. Colonel Simpson read the words of Lord Canning, and then, on his own behalf, spoke feelingly to the men in their own language. He told them that their reputation would be enhanced throughout India. The sipahis (soldiers) seemed in the highest spirits, and sent up a ringing cheer.

But that evening, whilst the officers and the new arrivals from England were dining at the regimental mess, they rose in revolt. While one detachment attempted to secure the guns of the native battery, the bulk of the men gathered in front of their lines and received their officers as they rode to the spot with murderous volleys. Amongst those who fell were Captain Plunkett, the Adjutant, Lieutenant Steward, the Quarter-Master, Lieutenant Hawes, and Ensigns Pringle and Munro. Of officers not belonging to the regiment, the Fort Adjutant, Major Birch, Lieutenant Innes of the engineers, and eight of the un-posted boys just arrived from England, were mercilessly slaughtered. Nor was the attempt to capture the guns less successful. Despite the travails of Lieutenant Hardward, who narrowly escaped with his life, and of Lieutenant Alexander of the Oudh Irregulars, who was killed, the guns were dragged into the lines of the mutineers. The native gunners, in fact, and the troopers of the Oudh Irregulars had fraternised with the rebellious sipahis. The other officers of the 6th succeeded in securing refuge within the fort.

At the moment the fort as a secured refuge seemed very doubtful. And if the fort were to go, the sacrifice of the lives of those behind its ramparts would be the least part of the evil. The strongest and most important link between Calcutta and Kanhpur would in that case be severed. The bulk of the troops garrisoning the fort were Asians. There was one company of the 6th N. I., and there was the wing of the Sikh regiment of Firuzpur. On the other side were sixty-five European invalided soldiers, the officers, the clerks, the women, and the children. The temper of the Sikhs was known to be doubtful. News had arrived that, at Benaras, their countrymen had been fired upon by English gunners. Much depended upon the control possessed over them by their officers.

Fortunately their senior officer on the spot was a man of great daring, of strong character, and absolutely fearless. This was Lieutenant Brasyer, an officer who had been promoted from the ranks for his splendid conduct during the Sutlej campaigns of 1846, and who had risen to a high position in the regiment of Firuzpur. Brasyer`s keen instinct detected instantly the necessity of taking a quick and bold initiative. His Sikhs were supported by the guns on the rampart manned by the sixty-five invalids from Chanar. On his flank stood the hastily armed Europeans and Eurasians, to a point commanding the main gate. There was posted the company of the 6th N. I., where the Lieutenant ordered the sipahis to pile their arms. There was a moment of hesitation, but then, sullenly and unwillingly, the mutinous soldiers obeyed the order. The muskets were secured, and the sipahis were expelled from the fort.

The fort was secured, but the town, the civil station, and the cantonments were for the moment in the power of the rebels. Most cruelly did they abuse that power. The jails were broken open. Not only were the European shops plundered, the railway works destroyed, and the telegraphic wires torn down. The Europeans and Eurasians, wherever they could be found, were also cruelly mutilated and tortured. The death that followed their unspeakable torments was hailed by the sufferers as a blessed relief. The treasury was sacked also. Then the sipahis, flooded with blood and gold, abandoned the intention they had previously announced of marching to Delhi. They thus formally disbanded themselves and made their way, in small parties of twos and threes, each to his native village.

Their departure did not for the moment affect the state of affairs in the city and the station. The land-owners, influenced mainly by their dislike of the system known as the Thomasonian system, had risen about the city and in the neighbourhood. A day or two later there came to lead them a man who styled himself the `Maulavi,` and who possessed considerable organising powers.