Introduction

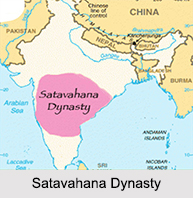

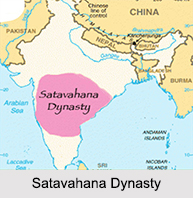

Satavahana Dynasty emerged in the southern part of India and expanded almost throughout the country. They ruled from Pune in Maharashtra to Coastal Andhra Pradesh. The Satavahana Empire was also known as the "Andhras" or the Andhra Dynasty. They were also called as the Andhras in Deccan and their capital was at "Paithan" or "Pratishthan". The Andhras were ancient people and they are mentioned in the Aitareya Brahmana. They played the most significant role in Indian history in the period between the fall of the Mauryas and the rise of the Gupta Empire.

Satavahana Dynasty emerged in the southern part of India and expanded almost throughout the country. They ruled from Pune in Maharashtra to Coastal Andhra Pradesh. The Satavahana Empire was also known as the "Andhras" or the Andhra Dynasty. They were also called as the Andhras in Deccan and their capital was at "Paithan" or "Pratishthan". The Andhras were ancient people and they are mentioned in the Aitareya Brahmana. They played the most significant role in Indian history in the period between the fall of the Mauryas and the rise of the Gupta Empire.

Origin of Satavahana Dynasty

Satavahana Dynasty was established in the 1st century BC in the western Deccan Plateau. As the name suggests it was evident that the Satavahana Rulers had emerged from the Andhra region or the delta areas of Krishna River and Godavari River. The Satavahana Dynasty was built up on the ruins of the Maurya Empire and around 1st century AD. The general belief about the Satavahana rulers is that the kingdom originated in the west and later on expanded their rule towards the east.

Rulers of Satavahana Dynasty

The rise of Satavahana Dynasty follows the pattern of chiefdom to kingdom. It has been recorded that the kings used to practice Vedic sacrifices as an act of legitimation. It was also believed that the Satavahanas had developed political ambitions because they carried out administrative functions during the reign of the Mauryas.

Simuka was the founder of the Satavahana Dynasty and he is believed to have destroyed the Sunga Power. Gautamiputra Satakarni, one of the earliest Satavahana king had received wide recognition because of his policy of military expansion. Satakarni carried on expansion through the entire country and had become famous during that era as a king of great power and valour. After Satakarni, the Satavahana dynasty was succeeded by Vasishthiputra. He had said that Satakarni was the one who had stopped the contamination of the four Varnas and had furthered the interests of the twice-born. He had also said that during the rule of the first Satavahana king, the Deccan served as a corridor not only for the passage of politics but it also served as a link to spread tread and the religious faiths like Buddhism and Jainism.

Simuka was the founder of the Satavahana Dynasty and he is believed to have destroyed the Sunga Power. Gautamiputra Satakarni, one of the earliest Satavahana king had received wide recognition because of his policy of military expansion. Satakarni carried on expansion through the entire country and had become famous during that era as a king of great power and valour. After Satakarni, the Satavahana dynasty was succeeded by Vasishthiputra. He had said that Satakarni was the one who had stopped the contamination of the four Varnas and had furthered the interests of the twice-born. He had also said that during the rule of the first Satavahana king, the Deccan served as a corridor not only for the passage of politics but it also served as a link to spread tread and the religious faiths like Buddhism and Jainism.

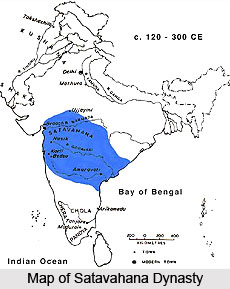

Till the end of 2nd century, the Satavahana dynasty expanded from western India to the Krishna delta and northern Tamil Nadu but this expansion did not continue for long. In the very next century, the power of the Satavahana rulers weakened due to the increasing power of the local governors all of whom claimed independent states for them. The Satavahana territories were divided into small provinces, each under civil and military officers. During the Satavahana reign many of the courtiers were allowed to marry in the royal family because it was believed to be a way to show their loyalty to the king. They were also allowed to mint their own coins.

Administration of The Satavahanas

It is the immediate effect of the fall of the Mauryan Empire and the abrupt confusion that caused due to this downfall led to the birth of another dynasty, which was famed as the Satavahanas Dynasty. It was also known as the Andhra dynasty. For nearly four hundred years the Satavahanas ruled the Andhra desha, which indeed included the Deccan. Monarchal system of administration prevailed during the reign of the Satavahanas. Hence the success of the administration depended upon the ability of the king. The king rises in accordance with the rules laid down in the dharma shastras. Kingship was hereditary. The Satavahanas adopted the title of `Raja`. But they did not believe in the divine powers of a king. Hence the king was not an aristocrat though king wielded vast power, he was the head of the whole administration and was the supreme commander of the army; yet he was bound to rule in accordance with rule of the dharma.

It is the immediate effect of the fall of the Mauryan Empire and the abrupt confusion that caused due to this downfall led to the birth of another dynasty, which was famed as the Satavahanas Dynasty. It was also known as the Andhra dynasty. For nearly four hundred years the Satavahanas ruled the Andhra desha, which indeed included the Deccan. Monarchal system of administration prevailed during the reign of the Satavahanas. Hence the success of the administration depended upon the ability of the king. The king rises in accordance with the rules laid down in the dharma shastras. Kingship was hereditary. The Satavahanas adopted the title of `Raja`. But they did not believe in the divine powers of a king. Hence the king was not an aristocrat though king wielded vast power, he was the head of the whole administration and was the supreme commander of the army; yet he was bound to rule in accordance with rule of the dharma.

The eldest son was appointed as the `Yuvaraj` but he could not render any help in the administration of the country. Other princes were appointed as the viceroys of the king.

Except the provinces which were under the control of the Samantas, the rest of the empire was divided into `janpadas` and `aharas`. A `janapad` was mainly comprised of several `aharas`. The name of the aharas was kept on the basis of the office and its governor was called `amach`. His post was not hereditary and time to time he was transferred to different places. Besides this, there were other officers such as `mahatarak`, `Bhandaragarik`, `hairanik`, `mahamatra`, `nibandhkar`, `pratihar` and `dutak` to help in the administration of kingdom.

The revenue of the state was not much during the reign of the Satavahanas. The rate of taxation was very low under the head of royal properties, land revenue, salt tax, export-import, etc. formed the revenue of the state.

Religious conditions During the Satavahanas

Like Sunga period, Satavahanas was also the period of the rise of the Brahmanism. Many types of yajanas were prevalent during this period. It can be known from Navaghat inscription that various kinds of sacrifices were performed during this period. Satkarni I is said to have performed two Asvamedha sacrifices and one Rajasuya sacrifices. Sacrifices like agnyadhaya, aiviramshtniva, gavamayina, angirasatirattra, aptoryama, angirasamayana, gargatisutra, chhandb gspapvarnanatiratra, trayodasaratra, etc. were also performed by satakarni I. The system of giving charity and dakshina to the Brahmans were also prevalent. There was prevalence of the rites and rituals all over the place.

Like Sunga period, Satavahanas was also the period of the rise of the Brahmanism. Many types of yajanas were prevalent during this period. It can be known from Navaghat inscription that various kinds of sacrifices were performed during this period. Satkarni I is said to have performed two Asvamedha sacrifices and one Rajasuya sacrifices. Sacrifices like agnyadhaya, aiviramshtniva, gavamayina, angirasatirattra, aptoryama, angirasamayana, gargatisutra, chhandb gspapvarnanatiratra, trayodasaratra, etc. were also performed by satakarni I. The system of giving charity and dakshina to the Brahmans were also prevalent. There was prevalence of the rites and rituals all over the place.

Along with the Brahman religion Vaishnava and Shaiva religion were also developing at that time. It can be understood from the names such as `Vishnupalit`, `Vishnudutt`, etc. Various inscriptions indicate the prevalence of the Vaishanava religion likewise names, such as, `Shivadutta`, `Shivabhut`, `Bhutapil`, `Skand`, etc., found in the inscriptions and elsewhere indicate the prevalence of the worship of lord Shiva in the society.

Thus it can be seen that Nandi, nag etc. were also worshipped in the society, places of pilgrimage were given much importance and it was considered pious to go and have bath in holy places and to give charity to the Brahman.

Because of the tolerant attitude of the Satavahana towards the religion, Buddhism also flourished during the reign of the Satavahana dynasty. The Buddhist caves and epigraphs built during this period at Pitalkhara, Nasik, Bhoja, Bedsaondane and Kuda and the Buddhist stupas at Bhattiprobe, Amaravati, Goli, Ghantasala and Gmmadidurru show the progress which Buddhism had made during this period. Various Buddhist caves built during this period. These were mainly of two types. Chaityagrihas or temples, and Layanas or residential quarters for Bhikshus. Buddhist monks and other followers of Buddhism were here to propagate their religion. Some of the Buddhist monks had enough money for this purpose. Buddhist Bhikshus remained in caves only in rainy season while in other seasons they propagated their religion.

Another important feature of the Satavahana period was that a large number of foreigners embraced either Buddhism or Brahmanism. Many of the Yavanas, Sakas, Phalanas and Abhiras settled in Gudoa and became follower of Brahmanism or Buddhism. For example Heliodorous, an ambassador to Bhagabhadra of Vidisa was a follower of Brahmanism.

Thus it can be seen that the Satavahana period was the period of religious tolerance. Not a single example of religious persecution is found.

Religion during Satavahanas in India

The Amaravati epigraphs mention some religious factions that flourished during the Satavahana period.

The Amaravati epigraphs mention some religious factions that flourished during the Satavahana period.

Buddhism: Sects

Four epigraphs from Amaravati mentions that`s the earliest among the prosperous religious sects were Chaityavamda (Chaityavada), or Chetika, or Chetikiya. This is the only sect mentioned both in eastern and western inscriptions. Since an Amaravati epigraph speaks of Chetikas at Rajagiri, and as the commentary on the Kathavatthu mentions Rajagirika as one the Andhaka sects, it is probable that this sect was an offshoot of the Chetika nikaya, whilst the Pubbasela (mentioned in the Alluru inscription), and Avarasela schools, (Andhaka schools) are mentioned by Kathavatta. As another but smaller stupa in the same place was dedicated to the Utayipabhahis - they were perhaps an offshoot of the Chaitikas. Rajagiri would also seem to have been a stronghold of the Chaitikas. Each sect had its mahanava-kammas and navakammas, monks some of whom were Sthaviras, Mahasthaviras and Bhadantas.

Monks and Nuns

Monks are called bhikhs, pavajitas, samanas, and pemdapatikas, nuns are called samanikas, pavajitikas, and bhikkhunis. It is no wonder that the flourishing Buddhist communities in western and eastern Deccan abounded with great teachers. In the western Deccan, mahasthaviras, sthaviras, bhanakas, and tevijas stepped on to the land, enlightening the faithful on the law of the Master. In eastern Deccan, monks, nuns and laymen flocked to teachers well versed in the Vinaya and Dhamma (Dhammakathikkas) and had bhana under them. Even nuns were teachers (upajhiyayini), and had scores of female pupils (atevasini) under them. Some monks and nuns were persons who had led the life of grihasthas (married persons). Monks and nuns were recruited from the lowest classes also.

The monks spent the rainy season (kept their vassa) in the caves scooped out on prominent rocks or in monasteries built by the faithful. The remaining part of the year was spent in religious tours. That is why most of the Buddhist monuments were erected in trade centres like Dhannakataka, Kalyan, Paithan and Nasik, and at Karla and Junnar which are situated in the passes leading from Konkan to the Ghats. The caves at Kanheri, which is near the sea and the sea-port of Kalyan, and Kuda, Mahad, and Chiplun situated on creeks, show that monks and nuns travelled by sea also.

Brahmanical Religion

Brahmanism was also in a flourishing condition. Most of the Satavahana kings were followers of the Brahmanical religion. The third king of the line performed a number of Vedic sacrifices and named one of his sons Vedisiri. Later Satavahanas were also followers of Brahmanism - Gotami Putra Satakari was a supporter of the Brahmins. He was not only learned in the traditional wisdom, but imitated epic heroes like Rama, Kesava, Arjuna, Bhimasena, and Puranic figures like Nabhaga, Nahusa, Janamejaya, Sagara, Yayati, and Ambarisa. Since Gotami speaks of Kailasa, he and his follows were devotees of Siva. Inscriptions found speaks that Brahmanism was flourishing more outside Satavahana dominions viz., in Gujarat, Kathiawad, Rajaputana, and Ujjain.

The Naneghat record begins with adoration to Dharma, Samkarsana, Vasudeva, Indra, the Sun and the Moon, the guardians of the four quarters of the world viz., Vasava, Kubera, Varuna and Yama. The Saptasatakam mentions wooden images of Indra which were worshipped. Worship of Krishna is indicated by the names like Govardhana, Krishna, and Gopala. In the Saptasatakam we find the Krishna legends fully developed. Krisna is called Madhumathana and Damodara. Gopis and Yasoda are also mentioned and also the jealousy of shepherdesses against Radha.

Brahmanism was also in a flourishing condition. Most of the Satavahana kings were followers of the Brahmanical religion. The third king of the line performed a number of Vedic sacrifices and named one of his sons Vedisiri. Later Satavahanas were also followers of Brahmanism - Gotami Putra Satakari was a supporter of the Brahmins. He was not only learned in the traditional wisdom, but imitated epic heroes like Rama, Kesava, Arjuna, Bhimasena, and Puranic figures like Nabhaga, Nahusa, Janamejaya, Sagara, Yayati, and Ambarisa. Since Gotami speaks of Kailasa, he and his follows were devotees of Siva. Inscriptions found speaks that Brahmanism was flourishing more outside Satavahana dominions viz., in Gujarat, Kathiawad, Rajaputana, and Ujjain.

The Naneghat record begins with adoration to Dharma, Samkarsana, Vasudeva, Indra, the Sun and the Moon, the guardians of the four quarters of the world viz., Vasava, Kubera, Varuna and Yama. The Saptasatakam mentions wooden images of Indra which were worshipped. Worship of Krishna is indicated by the names like Govardhana, Krishna, and Gopala. In the Saptasatakam we find the Krishna legends fully developed. Krisna is called Madhumathana and Damodara. Gopis and Yasoda are also mentioned and also the jealousy of shepherdesses against Radha.

The earliest recorded reference to the Srisailam occurs in a Satavahana inscription in an excavated shrine in Nasik belonging to 2nd century A.D. Lord Mallikarjuna (Siva) and Devi Bhramaramba presides in the Saivaite temple of Srisailam (on the top of a hill named Sriparvata in Kurnool district). The Vakatas, the Kakatiyas and the Vijayanagar rulers held this temple in great veneration. In 1674, Shivaji who visited this temple was overcome with emotion. He built one of the gopuras and left behind Maratha soldiers to defend the same. To this day, their descendants come to Srisailam once a year to celebrate a festival in their honour.

Names like Vishupalita, Venhu, and Lachnika point in the same way to the worship of Vishnu. In the Saptasatakam, Hari or Trivi-krama is said to be superior to other Gods. The birth of Lakshmi from the Ocean of Milk is also mentioned.

Social condition during the Satavahanas

Divided into four main classes the social condition during the Satavahanas was then rather contemporary.

The whole society was divided into four main classes, as for example `maharathis`, `mahabhojas` and `mahasenapatis` belonged to the first class and that was the highest class in the society. The `Samantas` also belonged to this class. `Mahabhojas` belonged to north konkar whereas `maharastis` belonged to the contrary above the western ghats.

The second class comprised of the officials as well as non officials. Amathas, mahamatias and chandrikas were the officials which formed this class. Among the non officials were the naigama or merchant, the sarthvaha or the head of a carvan of traders and the stresthin i.e. head of trade guide, lekhaka or scribe, vaidya or physician, halakiya or cultivator, suvarnkara or goldsmith and gandhika or druggist etc. formed the third class. Lastly the fourth class was comprised of the vardnika or carpenter, malakara or the Gardner, lohavanija or blacksmith and dasaka or fisherman.

Condition of women: The condition of women was good during the reign of Satavahanas. Their status was pretty high in the society. In times of emergency they took upon themselves the task of looking after the administration of the kingdom as well. Several names of the sons, such as Gautamputra Satkarni, Vasisthiputra Satkarni etc., which were after the name of their mothers, indicate the high and respectable position of women in the society. Probably women were imparted education from the beginning. Besides administrative works, women also participated in religious activities. Naganika performed two Asvamedha yajna along with husband. Widows were not subjected to sufferings and were respected as mothers. No such example is found which may indicate that there was purdah system among the women.

Economic condition during Satavahanas

The economic condition of the Deccan was very good during the reign of the Satavahanas. Beside agriculture many other trades and industries were also popular. The merchants had organized themselves into srenis. The organization of these srenis is one of the special features of the period of Satavahanas. There are different references about the guilds of oil pressure, hydraulic machine artisans, potters, weavers, corn dealers, and bamboo workers. These guilds were the normal feature and very popular in the north as well as in south India. There must have been many more guilds about which the information is not available. These srenis also performed the works. People deposited money in it and received interest. Often people deposited their properties for the whole life. The rate of interest varied and it was probably from 9% to 12% per annum.

The economic condition of the Deccan was very good during the reign of the Satavahanas. Beside agriculture many other trades and industries were also popular. The merchants had organized themselves into srenis. The organization of these srenis is one of the special features of the period of Satavahanas. There are different references about the guilds of oil pressure, hydraulic machine artisans, potters, weavers, corn dealers, and bamboo workers. These guilds were the normal feature and very popular in the north as well as in south India. There must have been many more guilds about which the information is not available. These srenis also performed the works. People deposited money in it and received interest. Often people deposited their properties for the whole life. The rate of interest varied and it was probably from 9% to 12% per annum.

Commerce: Trade and commerce flourished during the reign of the Satavahanas. Bhadoch, Sopara, Malyana etc. were the important harbours. Goods were exported to foreign countries from these harbours. Nasik, Junar, Praisthan, Ghaukat, Karhatak were the main commercial centres. These cities were linked with each other through the roads. During the period of Pulutnavi ii to the reign of Sriyana there existed not only the commercial relations with the far east, but also colonization of that area had been successfully made.

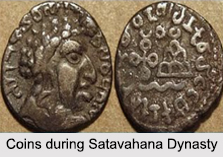

Currency: Coins were very much prevalent during the Satavahana period. Many types of coins were prevalent at that time. Most of the coins were made of gold which were called `suvarna`. A gold coin was equal to 35 silver karshapanas. The weight of one karshapana was nearly 1454 grains and one ratti was equal to 183 grains. `Kushan` was another type of silver coin. Small coin of silver and copper were used for day-to-day transactions. These were called `karshapanas.`

Lending and borrowing: Lending and borrowing of money was also prevalent during the Satavahana period. The rate of interest on the deposition of money and the property, varied from 9% to 12% per annum. Compared to the modern rate of interest, it is obvious that rate of interest was higher during this period.

However, it is clear that people preferred to spend the money rather than to deposit it. The economic condition of the people was good. People used to live happily without any tension.

Literature and art During the Satavahanas

From literary point of view this was the period of the rise of the Prakrit language. All the inscriptions of the Satavahana king are in Prakrit language. Halla was the greatest poet of this period. He composed `Saptshati` in Prakrit language. `Brihatkatha` of Gunagya was also the composition of this period. According to Allen a scholar named Sarvavarman wrote `Katantra`. This was a book on grammar during this period.

From literary point of view this was the period of the rise of the Prakrit language. All the inscriptions of the Satavahana king are in Prakrit language. Halla was the greatest poet of this period. He composed `Saptshati` in Prakrit language. `Brihatkatha` of Gunagya was also the composition of this period. According to Allen a scholar named Sarvavarman wrote `Katantra`. This was a book on grammar during this period.

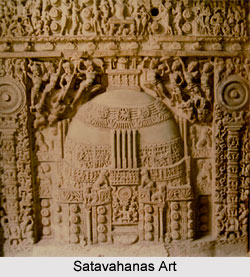

The contribution of the Satavahana period in the field of art is also great and mentionable. The remains of the stupas and sculptures of this period have been found in sites in Andhra at Goli, Jaggayapata, Bhattiprabe, Ghantasala, Amaravati and Nagarjuna Konda. The stupas of Amaravati are the largest and finest in quality. In the opinion of sir John Marshall "There is greater originality, freedom of treatment, spontaneous exuberance in the art of amaravati. The relief of Amaravati indeed appear to be as truly Indian in style as those of Bharhut and Ellora. They followed as a natural sequence on the Mauryan art, when that art was finding expression in more conventionalized forms. They have inherited certain motive and types which filtered from the north-west but these elements have been completely absorbed and assimilated without materially influencing the indigenous character of the sculptures."

In the field of paintings also much progress had been achieved. The architecture was also highly developed. Many Chaitya and Guhagriha i.e. cave-houses built by the Buddhists during this period. These are the fine examples of the art as well.

Ancient Sculptures of the Satavahana Empire

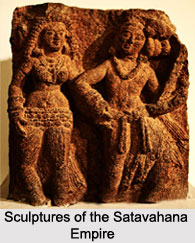

Ancient sculptures of the Satavahana Dynasty remained iconic till their rule in the 2nd century. Primarily the Satavahana style of art and sculpture was dominated by the faith of Buddhism.

Ancient sculptures of the Satavahana Dynasty remained iconic till their rule in the 2nd century. Primarily the Satavahana style of art and sculpture was dominated by the faith of Buddhism.

Various schools of sculptures flourished under the patronage of the Satavahana rulers. The Amravati School of sculpture came to the forefront as one of the most popular styles of Buddhist art. The sculptures here show some of the traces of the influence of the Gandhara Amaravati stupa and the Mathura schools to some extent.

History of Ancient Sculptures of the Satavahana Empire

The earliest Sculpture of the Satavahana Empire is the Bhaja Vihara cave which marks the beginning of sculptural art in around 200BC. It is generously decorated with carvings and even pillars have a lotus, crowned with sphinx-like mythic animals. The Satavahanas were also called the Andhra dynasty, which has led to the statement that they initiated in the Andhra region, the delta of the Krishna and Godavari rivers on the east coast, from where they moved westwards up the Godavari River.

The Satavahanas seems to commence as feudatories to the Mauryan Empire. They seem to have been under the rule of Emperor Ashoka. The founder of the Satavahana Empire was Simuka. Many statues and images were made all through this era. Most of the images portray scenes from the life of the Buddha. The sights depicting Buddha`s feet are worshipped mainly as an exclusive sculpture at the Amravati Stupa while at Nagarjunakonda, the sculpture depicting Buddha giving a speech, throw an enchantment of peacefulness.

Features of Ancient Sculptures of the Satavahana Empire

Lord Gautama Buddha was not represented in a human form. This was known to be a significant feature of the Satavahana sculptures. The features of Satavahana sculptures are also found in the sculpture of Nagarjunakonda. At Nagarjunakonda the sculptural tradition of Amaravati seems to continue. Here too, the Buddhist themes dominate the entire picture of artistic creations. Episodes from Gautama Buddha`s life have been transferred on stone. But the outstanding example of the sculpture of that ages and art of Satavahanas is the depiction of the Enlightened Buddha. The erotic sculptures are less in numbers but can be marked with their presence. The images were characterized by vigour, activity and grace.

The sculpture of Karle Chaitya is another example of the magnificence of the Satavahana architecture. The hall is more than 124 feet long, 46 feet broad and 46 feet high. It also marked with construction of the garbhagriha, the pradakshinapatha and the mandapa. Here, along with the doorway, even the elegant chaitya window, encompassing the woodwork of sculptures has remained till today. Sculpture of Kanehri has also been modelled on the particular style in which other Satavahana sculptures have been carved out.

The famous sculptures at Ajanta Caves also reflect the features of Satavahana art and architecture. The glory of the Satavahanas is, thus, rightly reflected in the tradition of art and architecture. In fact in many famous places in Andhra Pradesh like Goli, Jaggayapeta, Ghantasala, Bhattiprolu, Amaravati and Nagarjunakonda the remains of Satavahana sculptures have been discovered. A large number of Stupas had also been constructed under the regime of the Satavahanara rulers. The Bhattiprolu stupa, is a renowned sculptural beauty of the Satavahanas, which is engraved inscriptions in the Brahmi script, which is said to be closely associated to the Balinese, Burmese, Javanese, Thai and Indian Tamil and Telugu scripts.

Some more sculptures of the Satavahana Empire existed specifically are Dvarapala, Gajalaksmi, Shalabhanjikas, Royal Procession, Decorative pillar etc.

Women in the Satavahana Period in India

Women occupied a soaring pose in the Satavahana Period. In the western India caves and Amaravati inscriptions we encounter a number of ladies making very costly donations. A great number of the exquisitely sculptured rail pillars, toranas and stupa slabs at Amaravati were donated by ladies. Out of 145 epigraphs from Amaravati, 72, out of the 30 at Kuda, 13, out of the 29 from Nasik 16 either record gifts by women or gifts in which women are associated.

Women occupied a soaring pose in the Satavahana Period. In the western India caves and Amaravati inscriptions we encounter a number of ladies making very costly donations. A great number of the exquisitely sculptured rail pillars, toranas and stupa slabs at Amaravati were donated by ladies. Out of 145 epigraphs from Amaravati, 72, out of the 30 at Kuda, 13, out of the 29 from Nasik 16 either record gifts by women or gifts in which women are associated.

Women during the Satvahana period were founders of the Chetiyagharas at Nasik and Kuda. Men and Women stood equal in the construction of the Chaitya cave the most excellent mansion in Jambudvipa at Karla. The base to the right of the central door of the mansion carved with rail pattern, and the similar piece on the left were the gift of two nuns. A belt of rail pattern on the inner face of the gallery was also a bhikkhuni`s gift. The remaining pillar on the open screen in front of the verandah was the gift of a housewife. These examples without a doubt reveal that women were allowed to possess property of their own.

Women even got the titles of their husbands, such as, Mahabhoji, Maharathini, Bhojiki, Kutumbini, Gahini, Vaniyini, and so on. Research on the sculptures from Amaravati disclose that women worshipped Buddhist emblems, took part in assemblies, played instruments, enjoying music and dance and entertaining guests along with their husbands. In one of the panels of an outer rail pillar, we find depicted a disputation between a chief and another and the audience consists mostly of women who are represented as taking keen interest in what is going on. In some panels they are represented as watching processions. Widows were to shun ornaments, to be bent on self control and restraint and penance (Nasik inscription).

The Amaravati stone sculptures furnish ample information on dress and ornaments, of the women in those days. Except in some minor details, the dress and ornaments m vogue on both sides of the Deccan are the same. The most striking item of the dress of women and men is the headdress as in the Indus Valley. The former have their hair divided in front and running down to a knot at the back. Hung on the knot is a cord of twisted cloth or hair drawn in two or four rows. Sometimes we come across two strings in four rows ending in tassels. Some women have their hair done in the pointed knot sideways. In some the knot is done near the forehead with a string of beads.

Western Deccan women sometimes covered their head with a piece of cloth. Sometimes a thick cloth runs round the head. At Kuda, a woman wears a long cap, conical in shape. Perhaps it is the combing done in that shape. Generally a string or strings of beads adorn the forehead and the knots. Men wore a high headdress. The general custom was to have the hair knotted in front and covered to a great extent by a twisted cloth running down. The knot was adorned in front by a horseshoe shaped or chaitya-arch shaped ornament. Some Amaravati and Nagarjunakonda men wear knots unadorned by ornaments. Lay disciples and even servants have hair done in knots. In one of the Amaravati sculptures a groom has let the hair run down and secured it by bands at three places. One of the male figures in the facade of the Chaitya cave at Kanheri has a very low turban fully ornamented, the ornaments even hiding the knot of hair on the left.

Women were scantily dressed like men. Twisted cloth running in two or three rows below the waist and knotted at the right, the ends, however, hanging from the knots, and sometimes also four of five strings of beads held together by a clasp, constituted the main part of their dress. Men wore underclothes. There is only one instance among the sculptures of a woman covering her breast.

Both Men and women wore ornaments. Heavy rings, sometimes two in each ear, sometimes rows of beads joined together, constituted their ear ornaments. Even kings wore ear ornaments. The representation of Vasithiputa Siri - Satakani and Siri - Yajna Satakani on their silver coins show us well-punched ears. They wore bracelets and bangles with this difference, sometimes women wore bracelets covering the whole of the upper arm, and bangles running up to the elbow. Sometimes the anklets were heavy rings two for each leg, while in other cases; each is a spiral of many columns.

The noses of women were unadorned, as it seems to have been at the Indus Valley. In this connection it is interesting to note a description of some of the Bhattiprolu remains given by Rea in his South Indian Buddhist Antiquities. They are coral beads beryl drops, yellow crystal beads, double hollow beads, garnet, trinacrias, pierced pearls, coiled gold rings and gold flowers of varying sizes.

From the inscription of Nayanika, the widow of Siri - Satakarni, son of Simuka in Naneghat in western Deccan, shows the power enjoyed by royal women. She governed the kingdom during the minority of Vedisiri. The Naneghat inscription of queen Nayanika describes the dakshina (gift) given on occasion of various sacrifices performed by the queen and her husband. They are 1700 cows and 10 elephants, 11,000 cows, 1000 horses, 17 silver pots and 14,000 karshapanas one horse chariot, silver ornaments and dresses - evidencing royal opulence and belief in charity.

Decline of Satavahana Dynasty

Satavahana Dynasty emerged in the southern part of India and expanded almost throughout the country. They ruled from Pune in Maharashtra to Coastal Andhra Pradesh. The Satavahana Empire was also known as the "Andhras" or the Andhra Dynasty. They were also called as the Andhras in Deccan and their capital was at "Paithan" or "Pratishthan". The Andhras were ancient people and they are mentioned in the Aitareya Brahmana. They played the most significant role in Indian history in the period between the fall of the Mauryas and the rise of the Gupta Empire.

Satavahana Dynasty emerged in the southern part of India and expanded almost throughout the country. They ruled from Pune in Maharashtra to Coastal Andhra Pradesh. The Satavahana Empire was also known as the "Andhras" or the Andhra Dynasty. They were also called as the Andhras in Deccan and their capital was at "Paithan" or "Pratishthan". The Andhras were ancient people and they are mentioned in the Aitareya Brahmana. They played the most significant role in Indian history in the period between the fall of the Mauryas and the rise of the Gupta Empire.

The Satavahanas Dynasty collapsed when Abhiras seized Maharashtra and Ikshwakus and Pallavas appropriated the eastern province. Their greatest competitors were the Sakas who had established their power in upper Deccan and Western India. As the Satavahana dynasty fell down, the governors of the kingdom followed a similar pattern and each of them tried to form an independent unit of their own. The declining power of the Satavahana was targeted by the Abhiras and the Traikutakas of western India.