Bells symbolize what exists within each human being, but these are not sounds that can be heard by ones ears, these actually resemble the inner sound. In India, especially South India, the bell plays a significant role in the life of every Indian, right from birth to death. Almost throughout India, the bells exhibit certain common features specially with regard to the material or metal with which they are made and the shape. Yet, the bells in different regions display subtle variations in ornamentation.

One does not know as to when exactly the first bell was made or used in India. In South India, there is hardly any concrete archaeological evidence for the use of bells in the early historical period (2nd century B.C. to 3rd century A.D.), although bell-like objects have been reported from ancient sites such as Nagarjunakonda in Andhra Pradesh. The ancient Tamil poems, incorporated in the Sangam literature (2nd century B.C. to 3rd century A.D.), contain references to bells, clearly proving the use of bells in this part of the country. For example, the Kurunthogai one of the eight anthologies (Ettuthojjai) of the Sangam literature, specifically refers to the manufacture of cast iron bells by the lost-wax method.

The concept of the `Bell of Justice` was also popular in ancient South India. It is believed that a king named Muchukunda Chola belonging to the Sangam Chola dynasty (2nd century B.C. to 3rd century A.D.) installed a `Bell of Justice` in his palace at Uraiyur near the modern city of Tiruchirappalli (Tiruchi) in Tamil Nadu. Citizens who felt that they had been cheated or wronged could walk up to the palace and ring this bell. On hearing the bell, the king would summon the citizens to the royal court to hear their complaints and dispense justice. Once, during the reign of the king Manunidhi Chola, a cow went up to the palace and rang the bell. When the cow was brought to the court, she tearfully informed the king that her new-born calf had been trampled to death by a chariot driven recklessly by the Chola prince. The prince who was called to the court reluctantly admitted his guilt. The king immediately ordered that the prince should be put to death! Repeated archaeological excavations at Uraiyur have, however, revealed no trace of the palace or the bell.

There are a few references to the bells in the temple inscriptions of medieval South India. These inscriptions mostly mention that kings and nobles gifted bells to temples.

Sri Vedanta Desika (1268-1369), the illustrious Sri Vaishnava philosopher and scholar is regarded as an incarnation of the divine bell. The figure of the saint is carved atop many bells in South India.Various Hindu religious texts such as the Padma Pur ana and the Devi Mahatmya describe the divine powers of the bell.

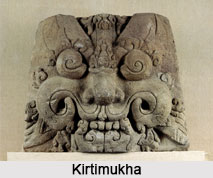

On the basis of size, the ritual bell has been broadly classified into two: mahaghanta (large bell, often so large that it is too heavy to be lifted by a single individual) and ghanta or kai mani in Tamil (the hand bell or easily portable bell). The bell used in domestic worship is invariably of the hand bell variety. In temples, both ghanta and the mahaghanta are used. The ghanta is venerated as the symbol of the musical instruments of the Gods. Each part of the intricately crafted hand bell is believed to represent a particular deity. Thus, Sarasvati, the Goddess of Wisdom, resides on its tongue or clapper, Brahma on its face, Rudra on its belly, Vasuki on its stem, while the entire body of the bell signifies the divinity of time. The handle at the top denotes the prana shakti (vital force or life-giving energy). This handle usually portrays the figure of a deity or a religious symbol appropriate to the temple where the bell is used.