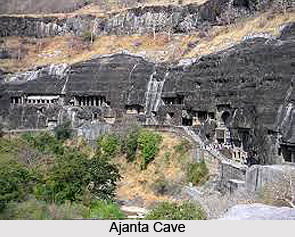

The Ajanta Caves, located in the Aurangabad District of Maharashtra state in India, are a remarkable collection of 29 rock-cut Buddhist cave monuments. Dating from the second century BCE to about 480 CE, these caves are widely regarded as masterpieces of Buddhist religious art and have earned the prestigious designation of being a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Ajanta Caves captivate visitors with their stunning paintings and rock-cut sculptures, which are considered among the finest surviving examples of ancient Indian art.

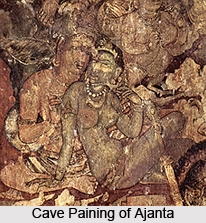

Textual records reveal that the Ajanta Caves served as a retreat for monks during the monsoon season. Furthermore, these caves provided a resting place for merchants and pilgrims in ancient India. Among the multitude of vivid colors and mural wall paintings that grace India`s history, Caves 1, 2, 16, and 17 of Ajanta represent the largest surviving corpus of ancient Indian wall-paintings.

Situated approximately 107 kilometers away from the city of Aurangabad, Maharashtra, the Ajanta Caves are nestled in a majestic horseshoe-shaped gorge, offering a captivating view of the picturesque surroundings. The caves were ingeniously carved into the rugged and broken hills of the northern scarp of the Deccan, where the Vagha River gracefully winds its way through the landscape, eventually merging into the Berar and Tapti valleys. Even in the heat of summer, the riverbed retains pockets of water, while a sudden downpour can transform the gorge and caves into a symphony of rushing waters.

Nestled within a panoramic gorge, overlooking a bend of the Waghora River in northern Maharashtra, the Ajanta Caves offer a breathtaking spectacle. Carved between the 2nd century BCE and the 5th century CE, these caves have managed to preserve their stunning paintings and sculptures remarkably well. It was only in the 19th century that these hidden treasures were discovered, revealing a visual narrative of Buddhism spanning from 200 BCE to 650 CE. The Ajanta Caves stand as a timeless testament to the beauty and antiquity of Indian and global art.

Ajanta Caves as UNESCO World Heritage Site

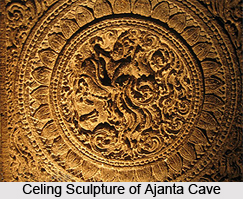

The Ajanta Caves in Maharashtra hold immense significance in the realm of Buddhist art and have played a crucial role in the development of art in India. Recognizing their cultural and historical value, UNESCO designated the Ajanta Caves as a World Heritage Site in 1983. The paintings on the walls and ceilings of these caves epitomize the artistic achievements of India`s Golden Age, often associated with the Gupta Empire. The sculptures within the caves showcase the creativity of the artisans, who brought human and animal forms to life with exceptional expressiveness.

Construction of Ajanta Caves

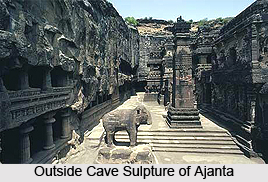

The construction of the Ajanta Caves occurred in two distinct phases. The first phase began around the second century BCE, while the second phase took place between 400 and 650 CE, according to earlier accounts, or in a brief period of 460–480 CE, as later scholarship suggests. These ancient monasteries (Viharas) and worship-halls (Chaityas) were meticulously carved into a 75-meter wall of rock. The caves are not only architectural marvels but also house intricate paintings depicting the past lives and rebirths of the Buddha, as well as pictorial tales from Aryasura`s Jatakamala. Additionally, there are rock-cut sculptures of Buddhist deities that adorn the caves.

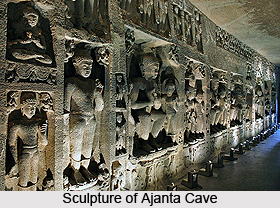

Sculptures at Ajanta Caves

Sculptures at Ajanta Caves

As visitors explore the caves, they are greeted by a wealth of artistic treasures that showcase the diversity and artistic prowess of ancient Indian civilization. The vivid and emotive paintings adorning the walls and ceilings depict scenes from the life of the Buddha, captivating narratives from ancient texts, and serene portrayals of Buddhist deities. The intricate rock-cut sculptures breathe life into human and animal forms, displaying a level of craftsmanship that remains unparalleled.

Scholars and art enthusiasts are particularly captivated by the Ajanta Caves due to their remarkable preservation and the insights they offer into the artistic heritage of India`s Golden Age. These caves stand as a testament to the ingenuity and creativity of the Gupta Empire, a period often referred to as the pinnacle of Indian civilization. The harmonious blend of architecture, sculpture, and painting found within the caves represents the zenith of artistic expression and reflects the profound spiritual devotion of the artists who created them.

Hinayana and Mahayana Phases

The Ajanta Caves can be categorized into two distinct phases: the earlier Hinayana phase and the later Mahayana phase. In the earlier phase, the Buddha was worshipped solely in the form of symbols. However, in the later phase, the Buddha was worshipped in physical form, resulting in a shift in artistic representations. The caves serve as a window into the evolution of Buddhist art and spiritual practices throughout history.

Groups of Caves

Ajanta caves can be broadly classified into two groups. The first group consists of 27 caves which are finished or almost finished caves and depict different forms of Buddha. It includes the sculptures and paintings of the earliest Buddhist architecture. The second group forms the rest of the two caves which are unfinished caves and are mostly not accessible to visitors. The first phase dates back to the 2nd century BCE to 1st century CE, followed by a second phase several centuries later.

Initially, 29 caves were numbered from 1 to 29, but further exploration revealed 36 distinct foundations. The set of 29 caves at Ajanta caves are numbered according to their sequential location along the cliff face, which does not correspond to the order in which they were constructed. These caves comprise of Chaitya Halls or shrines and Viharas or monasteries. The more prominent Hinayana caves are those numbered 9, 10 (both chaityas), 8, 12, 13 and 15 (all viharas), whereas the Mahayana monasteries include 1, 2, 16 and 17, while the chaityas are in caves 19 and 26. In ancient times, each cave was accessed from the riverfront by individual staircases.

Initially, 29 caves were numbered from 1 to 29, but further exploration revealed 36 distinct foundations. The set of 29 caves at Ajanta caves are numbered according to their sequential location along the cliff face, which does not correspond to the order in which they were constructed. These caves comprise of Chaitya Halls or shrines and Viharas or monasteries. The more prominent Hinayana caves are those numbered 9, 10 (both chaityas), 8, 12, 13 and 15 (all viharas), whereas the Mahayana monasteries include 1, 2, 16 and 17, while the chaityas are in caves 19 and 26. In ancient times, each cave was accessed from the riverfront by individual staircases.

Additional caves discovered later were designated with alphabetical suffixes, such as 15A, located between the original caves numbered 15 and 16. It`s important to note that the numbering system is purely for convenience and does not indicate the sequential order in which the caves were built.

History of Ajanta Caves

Chaitya halls were dedicated to Lord Buddha and were considered as the places of worship. These were large, rectangular chambers separated by rows of pillars into a central nave, surrounded by aisles on three sides, for circumambulation during prayer. It also had a sanctuary opposite the entrance. As it was dedicated to Buddha, it included many sculptures and paintings depicting the various incarnations of Buddha. The viharas, whereas were used by Buddhist monks for meditation and the study of Buddhist teachings. These were rectangular shaped halls with series of small cells attached on two sides. The side opposite the entrance contained an image of Buddha or a votive stupa.

The murals that surround the walls and ceilings of the caves depict the epic of Lord Buddha and various divinities of Buddhist. Out of these, the most important art forms are the paintings of the Jataka tales, which tells the stories about the previous incarnations of the Gautama Buddha as Bodhisattva. They also include the sculptures of Buddha that stand calm and serene in contemplation. These elaborate paintings and sculptures have a lot of exclusiveness since they have withstood all the ravages of time. One can also find in the caves a sort of illuminated history of the times - street scenes, court scenes, cameos of domestic life and even animal and bird studies come alive on these unlit walls.

These wall paintings and sculptures have been chiselled from rough rocks by the primitive inhabitants during the first and second century B.C. The art work is of great finesse and represents the level of skill the people of those times had. The popular Assembly Rock or Chaitya are examples of the ecclesiastical forms, but were undoubtedly derived from the apsidal halls of the secular communities and guilds which play so prominent a part in early Buddhist literature. They are found in the Caves Nos. IX and X at Ajanta.

The caves are carved out of flood basalt and granite rock of a cliff, part of the Deccan Traps formed by successive volcanic eruptions at the end of the Cretaceous geological period. The rock is layered horizontally, and somewhat variable in quality. This variation within the rock layers required the artists to amend their carving methods and plans in places. The inhomogeneity in the rock has also led to cracks and collapses in the centuries that followed, as with the lost portico to cave 1. Excavation began by cutting a narrow tunnel at roof level, which was expanded downwards and outwards; as evidenced by some of the incomplete caves such as the partially-built vihara caves 21 through 24 and the abandoned incomplete cave 28.

Caves 1 to 10

Caves 1 to 10

The Cave 1, positioned at the eastern end of the scarp, is the first cave encountered by visitors. Originally, this cave held a less prominent location at the far end of the row. Adjacent to Cave 1 is Cave 2, renowned for its remarkably preserved paintings adorning the walls, ceilings, and pillars. Similar in appearance to Cave 1, Cave 2 stands in better condition. Cave 3, however, remains an unfinished excavation project that was initiated towards the end of the final phase of work but was soon abandoned.

Cave 4, known as a Vihara, was sponsored by a wealthy devotee from Mathura. This cave, the largest vihara among the initial group, showcases remarkable architectural features and sculptures. Cave 5 stands as an incomplete excavation, intended to serve as a monastery. Despite lacking sculpture and other architectural elements, it does possess a notable door frame.

Cave 6, a two-story monastery has a sanctum and a hall on both levels. The lower level is adorned with pillars and includes attached cells. Similarly, Cave 7 functions as a monastery but is designed as a single-story structure. It features a sanctum, a hall embellished with octagonal pillars, and eight small rooms allocated for monks. Cave 8, yet another unfinished monastery, served as a storage and generator room for several decades in the 20th century.

Caves 9 and 10 hold a prominent position as the two chaityas or worship halls from the earlier period of construction, dating from the 2nd to 1st century BCE. Although they were reworked upon the completion of the second phase of construction in the 5th century CE, they bear the imprint of their early origins.

Caves 11 to 20

Within the Ajanta Caves complex, Cave 11, constructed during the period of approximately 462 to 478 CE, serves as a monastery with pillars featuring octagonal shafts and square bases. Cave 12, as per ASI, is an early stage Hinayana (Theravada) monastery from the 2nd to 1st century BCE. Unfortunately, the cave has suffered damage, with its front wall completely collapsed.

Cave 13 represents another small monastery from the early period, comprising a hall with seven cells, each of which contains two stone beds intricately carved out of the rock. Cave 14, although unfinished, exhibits notable carvings. The entrance door frame showcases sala bhanjikas, a type of decorative motif. Cave 15, a relatively complete monastery, provides evidence of ancient paintings. Its layout consists of an eight-celled hall leading to a sanctum, an antechamber, and a veranda adorned with pillars.

Cave 15A, the smallest cave in the complex, features a hall with a single cell on each side. Its entrance is located to the right of the entrance adorned with elephant carvings, leading to Cave 16. Cave 16, occupying a prominent position in the middle of the site, was sponsored by Varahadeva, the minister of Vakataka king Harishena. He also sponsored Cave 17 and Cave 26 with its sleeping Buddha. Cave 16holds significant influence over the architecture of the site.

Cave 17 and Cave 16 showcases two grand stone elephants at the entrance. Cave 17 also received support from local king Upendragupta, as indicated by an inscription found within. Cave 18, a small rectangular space with two octagonal pillars, connects to another cell, though its specific purpose remains unclear.

Cave 19 serves as a worship hall dating back to the fifth century CE. The hall features painted depictions of Buddha in various postures, adding a vibrant visual element to the cave. Cave 20, constructed in the 5th century, functions as a monastery hall. It comprises a sanctum, four cells for monks, and a pillared veranda that includes two stone-cut windows, allowing light to enter the space.

Caves 21 to 29

Cave 21 stands as a hall with twelve rock-cut rooms designated for monks, featuring a sanctum, twelve pillared and pilastered verandahs. The intricately carved pilasters showcase depictions of animals and flowers, adding to the visual allure of the cave. Moving on to Cave 22, it presents a small vihara with a narrow veranda and four unfinished cells. Situated at a higher level, this cave requires access via a flight of steps.

Cave 23, also unfinished, consists of a hall similar in design to Cave 21. However, it differs in terms of pillar decorations and the carvings of naga doorkeepers. Cave 24, resembling Cave 21, is also unfinished but considerably larger in scale. It houses the second-largest monastery hall after Cave 4, displaying the grandeur of the architectural endeavor.

Cave 25 serves as a monastery, featuring a hall similar to other monastic structures. However, it lacks a sanctum and instead includes an enclosed courtyard. This cave is excavated at an elevated level, adding a unique aspect to its design. Cave 26, a worship hall reminiscent of Cave 19, exhibits elements of a vihara design and is significantly larger in size. An inscription found within the cave attributes its creation to a monk named Buddhabhadra and his friend, a minister serving the king of Asmaka.

Caves 27 to 29 remain unfinished, with several sections either poorly excavated or in a state of ruin, limiting knowledge of their architecture and characteristics. Cave 27, potentially planned as an attachment to Cave 26, has suffered damage, with the upper level partially collapsed. Cave 28, an unfinished monastery, was only partially excavated and is situated at the westernmost end of the Ajanta complex. Lastly, Cave 29, an unfinished monastery located at the highest level of the Ajanta complex, was seemingly overlooked during the initial numbering system, and it physically lies between Caves 20 and 21.

Ajanta is a world in itself, shut in and aloof. In the spring, when the rains have broken and everything is green, its beauty is surpassing and appealing. To the north are the two fine hill-forts of Baithal-Wadi and Abasgarh dominating strategic points, undoubtedly ancient. Surprisingly, there is no sign of a town or village of any size nearby. The ancient pilgrims must have made their camp on the green bank at the turn of the river below the caves, where there is now a car-park. Four miles away is the Ajanta Ghat, the ancient highway to Asirgarh and the north. Southward lie Aurangabad, Paithan, Junnar, Thana, and the ports of Salsette, once thronged with the shipping of the African and Arabian trade.