Sitar is a string musical instrument said to have been introduced in India in the thirteenth century by Amir Khusrau. He was a statesman, poet and musician who was prominent at the courts of the rulers of the Khilji dynasty and Tughlaq Sultans of Delhi. An accomplished Indian musician, he is said to have introduced several Persian elements into Indian classical music, among them the sitar.

Sitar is a string musical instrument said to have been introduced in India in the thirteenth century by Amir Khusrau. He was a statesman, poet and musician who was prominent at the courts of the rulers of the Khilji dynasty and Tughlaq Sultans of Delhi. An accomplished Indian musician, he is said to have introduced several Persian elements into Indian classical music, among them the sitar.

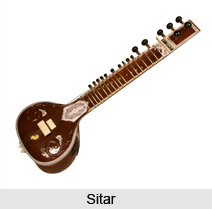

Origin of Sitar in India

It is said by some that the instrument Khusrau introduced in India was the three-stringed Persian Sehtar (seh means three and tar means string). Some others believe that the sitar stemmed from an instrument already known in various forms in India, the three-stringed (tritantri) veena, mentioned in the Sangeeta Ratnakara. This was adapted by Khusrau and given the Persian name Sehtar. Khusrau is believed to have reversed the order of the strings on this instrument and placed them as they are today.

As regards the development of the Sitar between the thirteenth and eighteenth centuries, it is conspicuous by its absence. In the sixteenth through seventeenth century, an instrument almost identical to the Persian Sehtar is to be found in the Mughal paintings. In the late eighteenth century, one Amrit Sen of Jaipur is said to have introduced three extra strings to the sehtar, thus increasing the number of strings to six. Of these six strings, four stand for melody and two for drone and rhythm. Later, a seventh string (a third chikari string) was added. Unlike the drone strings on a bin, the sitar chikari strings extend over the frets.

Structure of Sitar

The strings of the Sitar are all made of metal, either copper, brass, bronze or high-carbon steel. The frets on a sitar can be adjusted to a particular tuning called a `That`. The ten basic sitar thats are synonymous with the ten basic scale formations by which the Raagas of Hindustani music are most frequently organized. The sitar also has sympathetic strings. From twelve to twenty of these strings run parallel to, and below, the main strings. Tuned to the pitches of the Raaga being played, they vibrate in sympathy with the playing strings, creating a metallic, shimmering effect.

The stem of the sitar forms a neck that runs into a hollowed-out resonating chamber that is a gourd rather than wood. A second and smaller gourd, detachable on most sitars, is located at the top end of the instrument, near the tuning pegs. It functions as much for balance as for resonance. The frets are metal and are attached to the instrument with cords stretched across the underside of the neck.

Playing of Sitar

Sitarists sit cross-legged while playing their instrument. The main gourd rests on the sole of the left foot, and the neck slants upward at about a 45-degree angle from the floor. The index and middle fingers of the left hand stop the strings, just to the left of the frets, and the index finger of the right hand plucks the strings with a wire plectrum. Both upward and downward strokes are used, or, as Pt. Ravi Shankar describe them, inward and outward, referring to the position of the thumb. In sitar playing, the strings are often deflected across the frets so as to produce additional pitches or embellishments.

Ustad Vilayat Khan has evolved a new method of tuning the playing strings of the sitar, which necessitates the removal of the third string and the replacement of the heavier fourth and fifth strings by a single steel string. The effect of these changes is to eliminate the very low-pitched strings three and four, thereby reducing the range of the instrument.