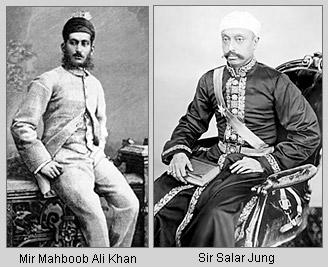

An important legacy of Sir Salar Jung"s regime which fell to Nawab Mir Mahboob Ali Khan to tackle was the unsettled question of Berar, which formed the northern frontier of the Nizam"s State and held a strategic position in the defense of the State. It was the most fertile of the Nizam"s territories. It had an area of about 18,000 sq. miles and a population of over 3 million, of whom 86 per cent were Hindus and 8 per cent Muslims.

An important legacy of Sir Salar Jung"s regime which fell to Nawab Mir Mahboob Ali Khan to tackle was the unsettled question of Berar, which formed the northern frontier of the Nizam"s State and held a strategic position in the defense of the State. It was the most fertile of the Nizam"s territories. It had an area of about 18,000 sq. miles and a population of over 3 million, of whom 86 per cent were Hindus and 8 per cent Muslims.

The Berar question remained of great consequence not only during his reign, but also throughout the whole region of Mir Osman Ali Khan, and indeed until the Hyderabad of the Nizams came to an end. The problem of Berar was intimately involved with the relations between Hyderabad and the British, whose handling of it has been justly and severely criticized as grossly unfair to a faithful and loyal ally. The question of Berar turned upon a revision of the military relations between the Nizam"s Government and the paramount power. It should be noted that in the various defensive alliances that were established between the English East India Company and Nizam Ali Khan, the Subadar of the Deccan from 1766 onwards, culminating in the treaties of 1768, 1790, 1798 and 1800, the Company"s Government never assumed responsibility for the internal security of the Nizam"s State. The British argument from the very beginning was that the Nizam, as an independent ruler, must possess an efficient, trained and well-equipped force of his own to collaborate with his ally, the East India Company"s Government, in fighting their common enemies.

The British were concerned that the forces maintained by the Nizam to co-operate with them as their ally should not be diverted from this co-operation by the needs of internal security. If the Nizam wanted to use them for this purpose, the Contingent must be largely increased and the British themselves must take over the forts etc. in Hyderabad, as per the consideration of the British. This line of thinking was grossly unfair to the Nizam. Without British pressure, his military establishment need not have been nearly so expensive. Thus as Lord Wellesley stated, if the Subsidiary Force are required for the support of the internal government upon all occasions that must be expected to occur. There is no difficulty in foreseeing that its number must be doubled at least, the forts must be delivered over to the British Government, and the whole system of the connection must be altered. This will certainly end in the annihilation of the Government of the Soubah of the Deccan.

Because of the financial instability of the Nizam"s Government, the British insisted that an assignment of territory must be made for the maintenance of the forces. Accordingly, by the Treaty of 1853 Berar was assigned to the management of the British Government and later, by the Treaty of 1860, the said districts were held in trust for the Nizam by the British Government for the maintenance of the Hyde¬rabad Contingent. During the minority of Mir Mahboob Ali Khan in the seventies the whole case of Sir Salar Jung and his Co-Administrator Amir Kabir Shamsul-Umara for the Restoration of Berar was based on Colonel Low"s statement that it was inherent in the Treaty of 1853 "that the Contingent might be dispensed with when the Nizam no longer required it". The Regents claimed that as the circumstances had changed for the better, the Contingent was no longer useful to the Nizam but it was the Government of India which benefited. They were willing to pay 30 lakhs a year for it, provided the Berar districts were restored to the Nizam"s Government and, therefore, the treaties should be revised accordingly.

On the other hand the British Government claimed that by the Seventh Article of the Treaty of 1853 the Contingent had to be maintained at all times whether in peace or war. It is evident that the phrase "at all times whether in peace or war" was a direct contradiction of the term "in time of war" as laid down by the Twelfth Article of the Treaty of 1800, while the Seventh Article of the Treaty of 1853 was inserted to annul for the Nizam the obligation imposed by the Treaty of 1800.

Further, the British Government"s stand was that by the Treaties of 1853 and 1860, Berar was made over without limit of time to them for the maintenance of the Hyderabad Contingent; the surplus, if any, from their administration being paid to the Nizam. Lastly, the Government of India, in its dispatch of 2 October 1874 in reply to the Ministers" Representation pointed out that the existing arrangement with Hyderabad rested not only on the Treaty of 1853 but also on the Treaty of 1860, regarding the voluntary conclusion of which, by the Nizam, there could not be any question whatever. Accordingly, the Nizam could not free himself from the engagements of 1853 and 1860 without the consent of the British Government. However, the Secretary of State for India, Lord Salisbury, in his dispatch of 28 March 1878, while declining to discuss any further the Berar question during the minority of Mir Mahboob Ali Khan, nevertheless, promised to consider any request should the Nizam, after undertaking the government of his State, desire to bring the whole of the Treaty engagements between the two governments under consideration.

After the assumption of the reins of government by Nawab Mir Mahboob Ali Khan, a fresh attempt to solve the Berar problem was made during the Viceroyalty of Lord Elgin, when Vikarul-Umara was the Nizam"s Diwan. A strong effort was made to lease out Berar for a limited period, though after its termination the lease would be renewable at an annual rent of 40 lakhs of rupees. The Nizam"s case was represented by the clever Parsi lawyer W. H. V. Hormuz Jung, aided by a retired Madras Civilian J. D. B. Gribble, who published articles in the "Pioneer" to show that the Nizam was not being fairly treated. With the help of statistical data of the Berar revenues and expenditures, Gribble clearly established that the surplus remittable to the Nizam was much more than admitted by the British Govern¬ment. In his Memorandum on the Berar question, Gribble proved that during the period 1898-99 the revenues of Berar amounted to Rs. 1,06,32,830, the Contingent cost Rs.38,16,280 and the adminis¬tration Rs.50,45,450. Assuming that in future the cost of the Contin¬gent would be Rs.40,00,000 and the interest on the 2 crore loan would amount to Rs. 10,00,000, there would remain Rs.22,00,000 for the cost of administration or 6 annas in the rupee. This being provided for, he suggested that the three districts of Buldana, Bassim and Wun might be restored to the Hyderabad Dominions which they adjoined.

As per the consideration of Nawab Mir Mahboob Ali Khan, the Berar Question was uppermost in the hearts of all Hyderabadis. The Hyderabad Government held that following the precedent of Afzal-ad Daulah"s period, when two of the assigned districts were restored to the Nizam"s Government, three of the six assigned districts ought to be taken back while the remaining three districts should be held in trust by the British Government as previously. But they were quite clear that the remaining three districts must never be merged into the British territory; for once merged they would never be restored to the Nizam"s Government. The Governor-General, Lord Curzon, was also willing to restore some of the Berar districts to the Nizam as an alternative plan for the settlement of the Berar Question.

Lord Curzon, though an able administrator, proved himself to be a short-sighted statesman. He failed to see the serious consequences which his plan, for a permanent lease of the Berar and for the merger of the Nizam"s Contingent into the Indian army would be essential for the future security and integrity of Hyderabad. It is true that financial instability of the State again provided a pretext for the British to seal the fate of Berar in a way convenient to themselves. It was Lord Curzon who realised that the Berar Question had not been dealt with in accordance with the best standards of an Englishman"s honour and integrity. The Viceroy considered, however, that a permanent solution of the anomalous and irregular situation of Berar would lead not only to greater administrative efficiency, but would also result in great economy in expenditure. For if Berar were to be amalgamated with the administration of an adjacent British province rather than being administered separately through the British Resident at Hyderabad or through the Chief Commissioner of Berar (as had hitherto been done), it would eliminate much unnecessary duplication of adminis¬trative work.

Lord Curzon, though an able administrator, proved himself to be a short-sighted statesman. He failed to see the serious consequences which his plan, for a permanent lease of the Berar and for the merger of the Nizam"s Contingent into the Indian army would be essential for the future security and integrity of Hyderabad. It is true that financial instability of the State again provided a pretext for the British to seal the fate of Berar in a way convenient to themselves. It was Lord Curzon who realised that the Berar Question had not been dealt with in accordance with the best standards of an Englishman"s honour and integrity. The Viceroy considered, however, that a permanent solution of the anomalous and irregular situation of Berar would lead not only to greater administrative efficiency, but would also result in great economy in expenditure. For if Berar were to be amalgamated with the administration of an adjacent British province rather than being administered separately through the British Resident at Hyderabad or through the Chief Commissioner of Berar (as had hitherto been done), it would eliminate much unnecessary duplication of adminis¬trative work.

Moreover, Lord Curzon also wanted to regularise the inconsistent position of the Hyderabad Contingent. He thought that if the Con¬tingent were to be wound up as a separate force and merged in the Indian army; its organisation would gain in military efficiency, while great economy in maintenance would result from the elimination of the staff required for a separate force. A further gain would be a clarification of the character of the Contingent. It had been started purely as a Nizam"s force, organised to keep law and order within the State. Since the Treaty of 1853 it had lost this character and had become an auxiliary force which, apart from its duties in the State, had been largely used for British military operations outside India such as those recently undertaken in Burma and in China.

Lastly, the Governor-General argued that the new arrangement would also serve the purpose of saving the position of the two million inhabitants of Berar who for the last half a century had become accustomed to British ideals of administration and justice. He felt that it would not be fair to transfer them to an inferior type of adminis¬tration, such as Hyderabad maintained in common with the other Indian States in general. This argument of the Governor-General was, however, specious in view of the fact that by the Treaty of 1860 the districts of Sholapore, Raichur, Lingsur and Naldrug together with taluks in the Bir and Amber Districts yielding an annual revenue of Rs. 21 lakhs were restored after a British administration of eight years, which excellent system was continued by Sir Salar Jung, though it differed from that operating in the rest of the Nizam`s dominions.

Moreover in the later period, Lord Curzon was quite mistaken in his appraisal of Nawab Mir Mahboob Ali Khan"s reaction to the permanent lease of Berar, the abolition of the Hyderabad Contingent, and its merger in the Indian army in consideration of a regular annual payment of Rs. 25 lakhs of the Berar surpluses to him by the British Government. The Nizam was fully conscious of the strategic importance of Berar and of the value of the Contingent as a force for the defence of the State. Mir Mahboob Ali Khan tried his utmost by means constitutional and diplomatic to get Berar restored to him without resorting to any such litigious unpleasantness with the British Government as had characterised the earlier efforts of Sir Salar Jung I.

During this time when the question of the replacement of the Treaties of 1853 and 1860 by a new arrangement in which the Berar districts were to be leased to the British Government in perpetuity was raised by the Resident, the Nizam was far from accepting it readily. After a detailed discussion of the proposed arrangement with the Council of Nobles, the unanimous decision was reached that the proposed arrangements should be rejected.

Nevertheless, the idea of solving the Berar tangle by a direct appeal to His Majesty the King was not given up. The Nizam even went so far as to suggest that he was ready to make a full and free gift of Berar and the Hyderabad Contingent for His Majesty"s acceptance and then ask for a portion of territory in lieu of the permanent lease, whether in Berar or anywhere else, which would yield him approximately the same revenue as the British Government had offered to pay him.

Nevertheless, the Nizam took a firm line about the Contingent. He objected to the proposal that the Contingent should be abolished and that it should be merged in the Indian Army. The Resident, writing to the Viceroy about his discussions with His Highness on the new treaty arrangements, stated that the Nizam was decidedly opposed to the clause of the treaty covering the Contingent. His Highness had deep concern over the future position of the Contingent in relation to the State.

No doubt it was Mir Mahboob Ali Khan"s anxiety to strengthen the defense position of Hyderabad which made him the first ruler of an Indian State to organise the Imperial Cadet Corps in 1900. This force was planned to serve as a frontier force to guard the interests of the British Empire but Lord Curzon insisted that the Imperial Cadet Corps was to be treated as the Indian State"s own forces.

It was by direction of the Nizam that the Minister, Maharaja Kishen Pershad, in replying to the Resident, Sir David Barr, about the confirmation of the clauses of the new Treaty, made it quite clear that the Nizam was resolved that the strength of the British forces, the Hyderabad Subsidiary Force and the Hyderabad Contingent and the duties they owed to the State must be kept intact as under Articles 2 and 3 of the Treaty of 21 May 1853. Therefore, in spite of the Nizam"s sincere endeavours to get Berar restored to Hyderabad and to keep the Contingent intact as his own force, he failed because of the Governor-General"s general drive for economy. Moreover, the Nizam"s hope of retaining British-trained forces for the defense of his State was only partially realised. The second part of the Treaty of 1902 runs as follows:

The British Government, while retaining the full and exclusive jurisdiction and authority in the Assigned Districts which they enjoy under the Treaties of 1853 and 1860, shall be at liberty, notwithstan¬ding any thing to the contrary in those Treaties, to administer the Assigned Districts in such manner as they may deem desirable, and also to redistribute, reduce, re-organise and control the forces now comprising the Hyderabad Contingent as they may think fit, due provision being made as stipulated by Article 3 of the Treaty of 1853 for the protection of His Highness"s dominions.

As a result, the deep disappointment which Nawab Mir Mahboob Ali Khan had felt at the unfortunate turn which the Berar problem had taken during his regime is clearly depicted in a letter he wrote a few months before his death to the Resident at Hyderabad, Colonel Pinhey. The Resident had requested the permission of the Nizam to include the Berar agreement in the proposed inscription on the pedestal of a statue of Lord Curzon which was to be set up at the National Museum in Calcutta.